THERYA NOTES 2026, Vol. 7:20-24

First photographic record of Leopardus pardalis

(Mammalia: Felidae) in Nichupté Lagoon, Quintana Roo, Mexico

Primer registro fotográfico de Leopardus pardalis

(Mammalia: Felidae) en la Laguna Nichupté, Quintana Roo, México

Patricia Cruz-Hernández1, Manuel A. Hernández-May2,3*, Aldo J. Martínez-Sánchez4, Carlos M. Villar-Bedian3, José A. Nungaray-Núñez5,

Juan F. García-Leyva1, Carlos A. Cárdenas-De la Rosa1 and Héctor Hernández-Maruri3

1Biota Corporativo Ambiental, Crisantemos 118, 86179, Blancas mariposas, Villahermosa Tabasco, México. E-mail: patriciacruz@biotaca.com (PC-H); galjfco@biotaca.com (JFG-L); cardenas_carlos22@outlook.com (CAC-DlR).

2Instituto Superior Hidalgo. Calle Cerrada de Juárez, 327 Col. Centro, C.P. 86706 Macuspana, Tabasco, México. E-mail: manuel.hz.may@gmail.com (MAH-M).

3Gestión y Asesoría Jurídico Ambiental S.A de C.V. Av. José Pagés Llergo 124, Lago ilusiones, 86040, Villahermosa, Tabasco, México. E-mail: manuel.hz.may@gmail.com (MAH-H); cmvillar@hotmail.com (CMV-B), hh_maruri@hotmail.com (HH-M).

4Dirección General de Carreteras, Secretaría de Infraestructura, Comunicaciones y Transportes, Av. Insurgentes Col. Noche buena, 1089, 03720, México D.F, México. E-mail: aldomartinez@sict.gob.mx (AJM-S).

5Ingeniería, Consultoría en Obras y Proyectos S.A de C.V. Margaritas 233, Blancas Mariposas 86170, Villahermosa, Tabasco, México. E-mail: jose.nungaray@icopingenieria.com.mx (JAN-N).

*Corresponding author.

The ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) is one of six species of felines found in Mexico. According to NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010, it is currently endangered in the country. The objective of this study was to document the presence of ocelots in the Nichupté mangrove protected natural area in Quintana Roo, Mexico. From March to November 2024, 16 camera traps were used for faunal sampling in this ecosystem for 275 days and 6,600 hours. From May to July 2025, daytime surveys were conducted for 65 days and 455 hours. Independent photographs and videos of several species of fauna were obtained. However, the ocelot was observed in only one photograph and in a single footprint on one day. This is the first documented instance of ocelots in the Nichupté mangrove ecosystem, which is of high biological and ecological importance. Furthermore, the presence of this species suggests that the ecosystem is healthy, as the ocelot is mainly associated with its food sources, such as rodents and birds.

Keywords: Camera trap; conservation area; endangered species; feline; new record; ocelot.

Leopardus pardalis comúnmente conocido como ocelote, es una de las seis especies de felinos que se distribuyen en México y actualmente en el país se encuentra en peligro de extinción de acuerdo con la NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010. Por lo que el objetivo del presente trabajo fue reportar la presencia del ocelote en el área natural protegida, manglares de Nichupté, en Quintana Roo, México. Mediante un muestreo faunístico con 16 cámaras trampas de marzo a noviembre 2024 (275 días y 6,600 horas) y recorridos diurnos durante mayo a julio 2025 (65 días/455 horas) en este ecosistema. Se obtuvieron fotografías y videos independientes con el registro de varias especies de fauna; sin embargo, el ocelote se observó solo en una fotografía y la huella en un solo día, este hallazgo es el primer registro de ocelote para el manglar de Nichupté, un área de gran importancia biológica y ecológicamente, además, la presencia de esta especie sugiere un buen estado de salud del ecosistema, ya que este felino se encuentra asociado principalmente a su alimentación (presas) como roedores y aves.

Palabras clave: Área de conservación; cámara trampa; especies en peligro; felino, nuevo registro, ocelote.

© 2026 Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología, www.mastozoologiamexicana.org

The ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) is one of six species of the Felidae family found in Mexico (Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2005; Ramírez-Bravo et al. 2010; Aranda 2012). It is the third largest spotted cat in Mexico and the largest in the genus Leopardus. It can be found in a variety of habitats associated with dense vegetation, such as tropical forests, mangroves, thorny scrub, grasslands, and swamps (Aranda 2005; Martínez-Calderas et al. 2011; Duarte-Muñoz et al. 2025). Ocelots are mainly nocturnal but also active during the day. They are solitary, territorial, and carnivorous, feeding mainly on small vertebrates (< 2.0 kg), such as rodents and birds (Murray and Gardner 1997).

Its distribution ranges from southern Texas to northern Argentina (Oliveira 1994; Aranda 2005). In Mexico, it is found along the Pacific and Gulf coasts, as well as in the states of Aguascalientes, Chiapas, Durango, Guanajuato, Hidalgo, Quintana Roo, Morelos, Nuevo León, Oaxaca, Puebla, San Luis Potosí, Sinaloa, Sonora, Tabasco, Tamaulipas, Veracruz, and Zacatecas (Iglesias et al. 2008; Bárcenas and Medellín 2010; Martínez-Calderas et al. 2011; Hernández-Flores et al. 2013; Valdez-Jiménez et al. 2013; Aranda et al. 2014; Gordillo-Chávez et al. 2015; Galindo-Aguilar et al. 2016; García-Bastida et al. 2016; Servín et al. 2017; Torres-Romero et al. 2017; Duarte-Muñoz et al. 2025).

Leopardus pardalis presents conservation challenges due to habitat loss and fragmentation, illegal hunting, and the illicit fur trade. These factors have caused population declines and local extinctions in many areas of the country (Sunquist and Sunquist 2002; Aranda 2005; Di Bitetti et al. 2008). In Mexico, it is currently classified as an endangered species, and hunting it is prohibited by Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (NOM-059-SEMARNAT 2010). The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN 2025) classifies it as a species of least concern. Its commercialization is regulated by Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES 2024), which places it in Appendix I. The objective of this study is to document the presence of L. pardalis in the Nichupté Lagoon mangrove reserve in Quintana Roo, Mexico. An ecosystem with scarce research and ecological importance. Essential for biodiversity conservation, it functions as a refuge and reproduction area for flora and fauna. Furthermore, it protects the coast from erosion and mitigates the effects of storms and hurricanes. Additionally, this system filters sediments and contaminants, maintains water quality, and functions as a valuable carbon reservoir. Simultaneously, they represent cultural heritage linked to traditional management practices and environmental education. Socially, they support fishing, tourism, and recreational activities. They contribute to the well-being and safety of the local population by reducing risks and maintaining the ecological productivity that sustains the regional economy.

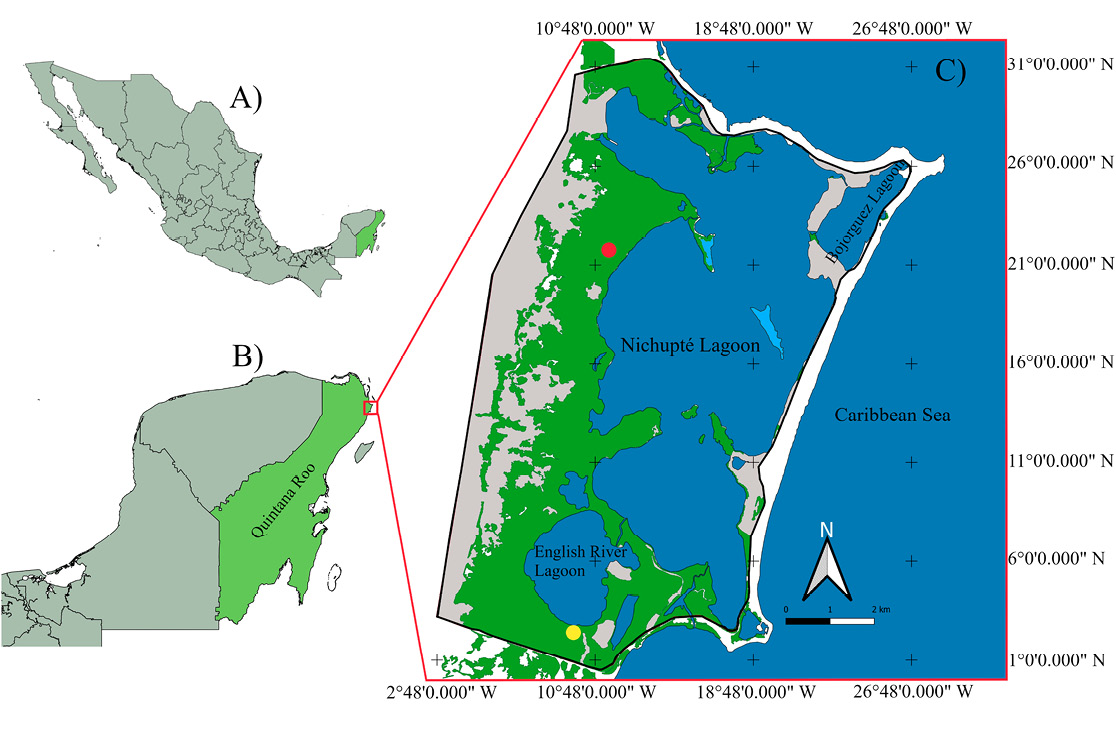

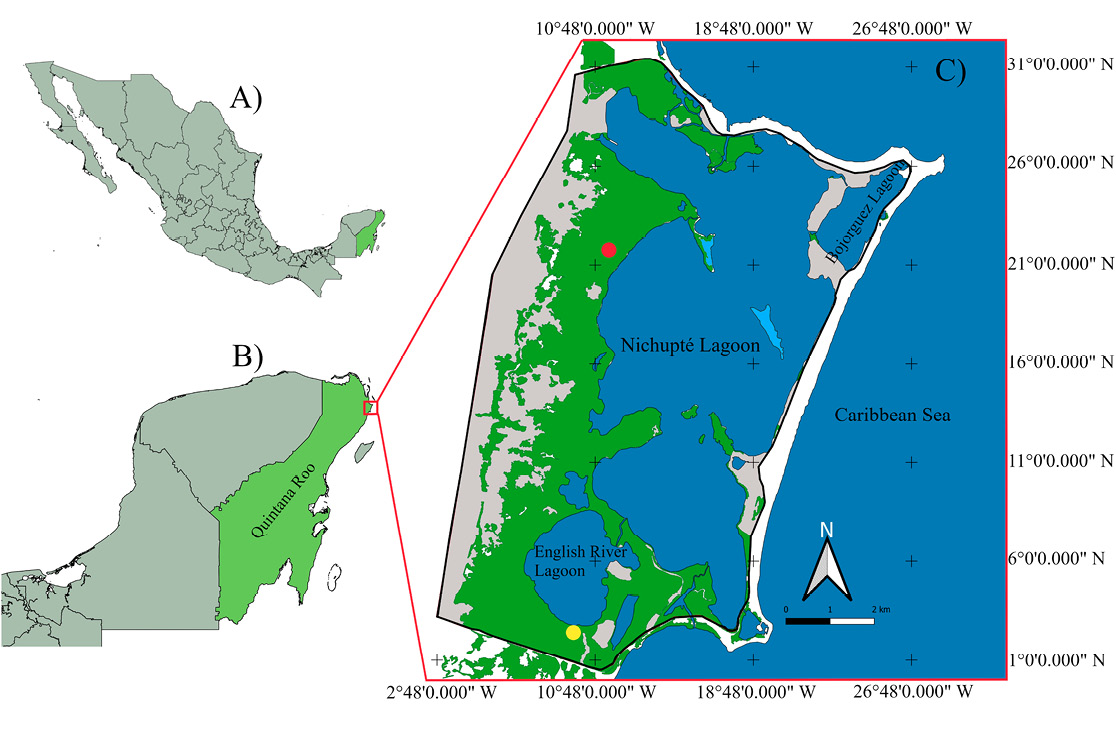

The records were obtained from the Nichupté Mangrove Protected Natural Area, which is located in the northeastern part of Quintana Roo, Mexico (Figure 1). This area has a surface area of 4,257 ha, dedicated to the protection and preservation of biodiversity with dominant mangrove vegetation of the species Avicennia germinans (black mangrove), Conocarpus erectus (buttonwood mangrove), Laguncularia racemosa (white mangrove), and Rhizophora mangle (red mangrove), and an elevation range of 0 to 4 meters above sea level (SEMARNAT 2014).

From March to November 2024, 16 sampling stations equipped with Browning Dark Ops HD Pro X camera traps were installed. The camera traps were configured in hybrid mode with 1080p HD video recording at 30 frames per second for 20 seconds, as well as three 20-megapixel photographs every 30 seconds. These stations were set up in areas where various bird species were concentrated, at the edges of and across natural channels that serve as corridors for different animal species. In total, the stations accumulated 275 days and 6,600 hours of sampling effort. Additionally, from May 2025 daytime surveys were conducted from 7 to 13 h. to detect traces of prey and tracks (paw prints) of this species in the ecosystem. Two people carried out these surveys, which covered a total of 65 days and 455 hours.

A clear photograph showing the size and pattern of the spots on the ocelot’s body was obtained, but the animal’s position did not allow its sex to be determined (Figure 2a). During daytime surveys, tracks of this species were identified (Figure 2b), indicating that the ocelot inhabits a large area in this region.

These records are the first to document the presence of L. pardalis in this natural area because it is not included among the 19 mammal species reported in the Nichupté mangroves (SEMARNAT 2014). The closest official records prior to these had been in the El Edén Ecological Reserve, located approximately 40 kilometers west of the mangroves (Torres-Romero et al. 2017).

The presence of L. pardalis in this protected natural area indicates the health of the local ecosystem because it regulates the population size of its prey (Pérez-Irineo and Santos-Moreno 2015). Similarly, the presence of ocelots suggests that the mangroves harbor a high diversity of prey, including small and medium-sized mammals, birds, and reptiles (Murray and Gardner 1997; Lima-Massara et al. 2015). Ocelots primarily consume prey weighing less than 2.0 kg. However, in the absence of larger carnivores, they are known to prey on larger mammals, such as coatis, raccoons, tepezcuinte, and opossums, which weigh up to 10 kg (Murray and Gardner 1997; De Cassia-Bianchi and Lucena-Mendes 2007). These mammals are very common in the Nichupté mangroves.

Like many ecosystems in the country, these mangroves are under anthropogenic pressure due to increased human construction. This restricts the distribution of the species, which is surrounded to the east, south, and north by human infrastructure and to the east by the Caribbean Sea. Consequently, the habitat of this feline and other species could be reduced, leaving them isolated and susceptible to disappearing over time (Pérez-Irineo and Santos-Moreno 2015).

These first records of the ocelot therefore indicate the urgent need to implement conservation measures, which would help maintain the habitat of this feline and its prey. Similarly, continued research in this area is recommended to provide more biological and ecological information on ocelots and other large mammals in this important area.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Secretary of Infrastructure, Communications, and Transportation (SICT) for funding the wildlife studies conducted in this area. We would also like to thank Fernando M. Contreras Moreno for helping to identify the L. pardalis footprint. To the anonymous reviewers who helped improve the quality of this document with their suggestions.

Literature cited

Aranda, M. 2005. Ocelote. Pp. 359–361 in Los mamíferos silvestres de México. (Ceballos, G and G. Oliva, eds.). Fondo de cultura económica/ Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO), México, D. F.

Aranda, J. M. 2012. Manual para el rastreo de mamíferos silvestres de México. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO). México, D. F.

Aranda, M., et al. 2014. Primer registro de ocelote (Leopardus pardalis) en el Parque Nacional Lagunas de Zempoala, Estado de México y Morelos, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 85:1300–1302.

Bárcenas, H. and R. A. Medellín. 2010. Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) in Aguascalientes, Mexico. Southwestern Naturalist 55: 447–449.

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). 2024. Apéndices I, II y III. http://www.cites.org/. Última visita: 18 julio 2025.

De Cassia-Bianchi, R. and S. Lucena-Mendes. 2007. Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) predation on primates in Caratinga Biological Station, Southeast Brazil. American Journal of Primatology 69:1173–1178.

Duarte-Muñoz, M. A., F. Cruz-García, and F. Cruz-Cobos. 2025. First record of ocelot Leopardus pardalis in a pine-oak forest of the Sierra Madre Occidental, Durango, México. Therya 6: 13–16.

Di Bitetti, M. S., et al. 2008. Local and continental correlates of the abundance of a neotropical cat, the ocelot (Leopardus pardalis). Journal of Tropical Ecology 24: 189–200.

Galindo-Aguilar, R. E., et al. 2016. First records of ocelot in tropical forests of the Sierra Negra of Puebla and Sierra Mazateca de Oaxaca, Mexico. Therya 7:205–211.

García-Bastida, M., et al. 2016. A new record of ocelot in Parque Ecológico Chipinque, Nuevo León, México. Therya 7: 187–192.

Gordillo-Chávez, E. J., et al. 2015. Mastofauna del humedal Chaschoc-Sejá en Tabasco, México. Theyra 6: 535–544.

Hernández-Flores, S. D., G. Vargas-Licona, and G. Sánchez-Rojas. 2013. First records of the Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) in the state of Hidalgo, Mexico. Therya 4:99–102.

Iglesias, J., et al. 2008. Noteworthy records of margay, Leopardus wiedii and ocelot, Leopardus pardalis in the state of Guanajuato, Mexico. Mammalia 72: 347–349.

International Union For Conservation of Nature (UICN). 2025. IUCN red list of threatened species. Version 2025.1. http:// www.iucnredlist.org. Última visita: 18 julio 2025.

Lima-Massara, R., et al. 2015. Ocelot population status in protected Brazilian Atlantic Forest. PloS One 10: e0141333.

Martínez-Calderas, J. M., et al. 2011. Distribución del ocelote (Leopardus pardalis) en San Luis Potosí, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 82: 997–1004.

Murray, J. and G. L. Gardner. 1997. Leopardus pardalis. Mammalian Species 548: 1–10.

Oliveira, T. 1994. Neotropical cats: ecology and conservation. Edufma, Säo Luís Maranhão. 220 p.

Pérez-Irineo, G. and A. Santos-Moreno. 2015. El ocelote: el que está marcado con manchas. Biodiversitas 117:1–5.

Ramírez-Bravo, O. E., et al. 2010. Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) distribution in the state of Puebla, Central México. Therya 1: 111–120.

Ramírez-Pulido, J., N. González-Ruiz, and H. H. Genoways. 2005. Carnivores from the Mexican state of Puebla: distribution, taxonomy, and conservation. Mastozoología Neotropical 12: 37–52.

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT). 2010. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-ECOL-2010, Protección ambiental-Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres-Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio-Lista de especies en riesgo. Ciudad de México, México.

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT). 2014. Programa de Manejo Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Manglares de Nichupté. SEMARNAT/CONANP, México, 137 pp.

Servín, J., et al. 2017. Record of live ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) at La Michilía biosphere reserve, Durango, México. Western North American Naturalist 76: 497–500.

Sunquist, M. and F. Sunquist. 2002. Wild cats of the world. The University of Chicago Press. Chicago, EE.UU. 443 pp.

Torres-Romero, E. J., et al. 2017. Ecology and conservation of ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) in Northern Quintana Roo, Mexico. Therya 8: 11–18.

Valdez-Jiménez, D., C. M. García-Balderas, and G. E. Quintero-Díaz. 2013. Presencia del ocelote (Leopardus pardalis) en la “Sierra del Laurel”, municipio de Calvillo, Aguascalientes, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (n. s.) 29: 688–692.

Associate editor: Jorge Ayala Berdón

Submitted: September 20, 2025;

Reviewed: December 17, 2025.

Accepted: January 12, 2026;

Published on line: February 11, 2026

DOI: 10.12933/therya_notes-25-226

ISSN 2954-3614

Figure 1. Geographic location of the sampling site. A) Mexico, B) Yucatan Penninsula and Quintana Roo state, C) Protected Natural Area, Nichupté Mangroves. Yellow circle: photographic record of L. pardalis, red circle: photographic record of the footprint.

A)

B)

Figure 2. Record of L. pardalis in the Nichupté mangrove protected natural area. A) Photographic record using a camera trap. B) Record using tracks.