THERYA NOTES 2025, Vol. 6: 201-206

Noteworthy records of the kinkajou (Potos flavus)

extend its northernmost Pacific slope distribution

Registros notables de martucha (Potos flavus), que extienden

su distribución más al norte en la vertiente del Pacífico

Tiberio C. Monterrubio-Rico1, and Juan F. Charre-Medellín*2,3

1Laboratorio de Ecología de Vertebrados Terrestres Prioritarios, Facultad de Biología, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo. Gral. Francisco J. Múgica S/N, Felicitas de Río, C. P. 58030, Morelia. Michoacán. México. E-mail: tiberio.monterrubio@umich.mx (TCM-R)

2National School of Higher Studies, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Antigua Carretera a Pátzcuaro 8701, Indeco la Huerta, C. P. 58190, Morelia. Michoacán. México. E-mail: jfcharre85@gmail.com (JFC-M)

3Laboratorio Sistemas de Información Geográfica y Percepción Remota, Facultad de Biología, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo. Gral. Francisco J. Múgica S/N, Felicitas de Río, C. P. 58030, Morelia. Michoacán. México. E-mail: juan.charre@umich.mx (JFC-M)

*Corresponding author

The kinkajou (Potos flavus) is a nocturnal arboreal carnivore, well adapted to forest canopies through its prehensile tail and flexible joints. Its distribution and ecology along the Mexican Pacific slope remain poorly understood due to its cryptic behavior. This study aims to define the species’ geographic range in this region more precisely. We reviewed all historical and recent records from scientific collections, digital platforms, and literature. Recent records were obtained through camera trap monitoring. Spatial data were analyzed using GIS to determine distribution by ecoregion and municipality. Records were categorized as historical (before 2000), contemporary (2001-2020), and recent (2021-2024), each included coordinates, habitat, and behavioral observations when available. The records confirm the species’ presence along northwestern Michoacán, including new localities extending its known range into Coahuayana. Historical evidence (1889) indicates past presence in the Balsas Basin, though no recent records exist there. Current distribution spans the Sierra Madre del Sur to coastal Michoacán. Camera traps revealed ground activity and site fidelity near springs during the dry season. This study refines the known distribution of Potos flavus, confirming its persistence despite recent forest loss and maintaining its Pacific northern limit. New behavioral observations suggest adaptations to hot, dry conditions, emphasizing the importance of conserving the species in its northernmost, drier range, where environmental pressures may shape its ecological responses.

.

Key words: Area fidelity; kinkajou; Michoacán; Procyonidae; water source.

La martucha (Potos flavus) es un carnívoro nocturno y arborícola, bien adaptado al dosel forestal gracias a su cola prensil y articulaciones flexibles. Su distribución y ecología a lo largo de la vertiente del Pacífico mexicano siguen siendo poco conocidas debido a su comportamiento críptico. Este estudio tiene como objetivo definir con mayor precisión el rango geográfico de la especie en esta región. Se revisaron todos los registros históricos y recientes provenientes de colecciones científicas, plataformas digitales y literatura. Los registros recientes se obtuvieron mediante monitoreo con cámaras trampa. Los datos espaciales se analizarán mediante SIG para determinar la distribución por ecorregión y municipio. Los registros se categorizaron como históricos (antes de 2000), contemporáneos (2001-2020) y recientes (2021-2024), incluyendo coordenadas, hábitat y observaciones de comportamiento cuando estuvieron disponibles. Los registros confirman la presencia de la especie en el noroeste de Michoacán, incluyendo nuevas localidades que amplían su distribución conocida hasta Coahuayana. Evidencias históricas (1889) indican su presencia pasada en la cuenca del Balsas, aunque no existen registros recientes allí. Su distribución actual abarca la Sierra Madre del Sur y la costa michoacana. Cámaras trampa registraron actividad terrestre y fidelidad al sitio cerca de manantiales durante la temporada seca. Este estudio refina la distribución conocida de Potos flavus, confirmando su persistencia a pesar de la reciente pérdida de bosques y el mantenimiento de su límite norte en el Pacífico. Nuevas observaciones conductuales sugieren adaptaciones a condiciones cálidas y secas, destacando la importancia de conservar la especie en su rango más septentrional y árido, donde las presiones ambientales pueden influir en sus respuestas ecológicas.

.

Palabras clave: Fidelidad de área; fuente de agua; martucha; Michoacán; Procyonidae.

© 2025 Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología, www.mastozoologiamexicana.org

The kinkajou (Potos flavus), also known as “Mico de noche” in Mexico, or kinkajou (Ford and Hoffmann 1988; Emmons and Feer 1997), is the most specialized arboreal carnivore in Mexico (Figueroa and Arita 2005). It uses its prehensile tail as an additional arm, in addition to adaptations such as flexible knees and ankle joints that allow the hind limbs to rotate, enabling the kinkajou to descend head-first into vegetation (Ford and Hoffmann 1988; Wainwright 2002). Although taxonomically a carnivore, its herbivore diet is broad and includes fruits, flowers, nectar, and leaves, from at least 119 plant species in 50 families, and to a lesser extent, small vertebrates, arthropods, and bird eggs (Janzen 1983; Reid 1997; Wainwright 2002; López-Cumatzi et al. 2025). The population ecology, actual distribution and conservation status of the species remain poorly understood in its Pacific range in Mexico, partly due to its strict nocturnal and arboreal habits (Monterrubio-Rico et al. 2013).

Historically, the distribution of P. flavus in Mexico extended from southern Tamaulipas to the Yucatan Peninsula, including Eastern San Luis Potosí, and Veracruz. For Western Mexico, the northern distributional limit was situated in Southeast Michoacán on the Pacific slope to Chiapas (Figueroa and Arita 2005; Monterrubio-Rico et al. 2013; Osorio-Rodríguez et al. 2023). The species in Mexico inhabits a variety of forest types, including tropical rainforests, cloud forests, tropical semi-deciduous forests, riparian forests, secondary vegetation, and sometimes orchards (Ford and Hoffman 1988; Figueroa and Arita 2005), from elevations at sea level to 2,200 m (Reid 1997; Figueroa and Arita 2005). The species is listed under special protection status in Mexico, NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (SEMARNAT 2010), due to forest loss, and hunting pressures, as reported in recent research (Hernández-Flores et al. 2018; Osorio-Rodríguez et al. 2023). And the species is internationally considered as of Least Concern, but with decreasing populations (Helgen et al., 2016).

The historic and actual distribution of kinkajou for the state of Michoacán was relatively uncertain for the northern portion of the Michoacan coast (northwestern Aquila and Coahuayana municipalities) (Monterrubio-Rico et al. 2013). The historic (before 2000) research effort occurred mainly on the remote wilderness areas of central and southern Michoacán coast, in particular on the Lazaro Cardenas and a report for Coalcomán fur trade, however, their presence was assumed as localities relatively near were reported for the neighboring Guerrero state (Ávila-Nájera 2006). In the absence of wildlife monitoring programs, and the increase in contemporary forest loss rates in the state (Loya-Carrillo and Mas-Caussel 2020), the aims of this report included to examine updated information in the context of previous reports (Monterrubio-Rico et al. 2013). To analyze new distributional records which implies modifications of the species observed range. In addition, to describe unusual behavioral ground level activity recordings.

In order to update the species status and distribution in Michoacán, we analyzed all available historical records, including those described in previous reports (Monterrubio-Rico et al., 2013) and combined data from field research including records from camera trap sampling, these records originated from a camera trap monitoring program designed primarily for the study of wild felids in the coastal–mountain region of Michoacán. Cameras were strategically placed along trails, dirt roads, and near springs within fragments of tropical forests, which also allowed for the incidental detection of other nocturnal and arboreal mammals such as Potos flavus. We also reviewed and included all kinkajou records available in databases and open online databases (Álvarez-Solórzano and López-Vidal 1998; Nagy-Reis et al. 2020), or platforms GBIF: Global Biodiversity Information Facility (www.gbif.org), MANIS: Mammal Networked Information System (www. manisnet.org), INaturalist Mexico (https://mexico.inaturalist.org/), and Portal de Datos Abiertos: UNAM: (http://datos abiertos.unam.mx), as well as scientific literature (Brand 1961; Sánchez-Hernández and Gaviño de la Torre 1988; Álvarez-Solórzano and López-Vidal 1998). P. flavus records were considered historic if they corresponded to an event (collected specimen, photograph, documented sighting) that occurred before year 2000, contemporary if occurred between 2000 and 2020, and recent if corresponded to the last five years. To determine the spatial distribution of Potos flavus in Michoacán, all georeferenced records (historical and contemporary) were plotted and analyzed in a Geographic Information System (GIS). Each record was inspected for its overlap with the corresponding ecoregion, of type vegetation and municipality boundaries following (Morrone et al., 2017; INEGI 2021).

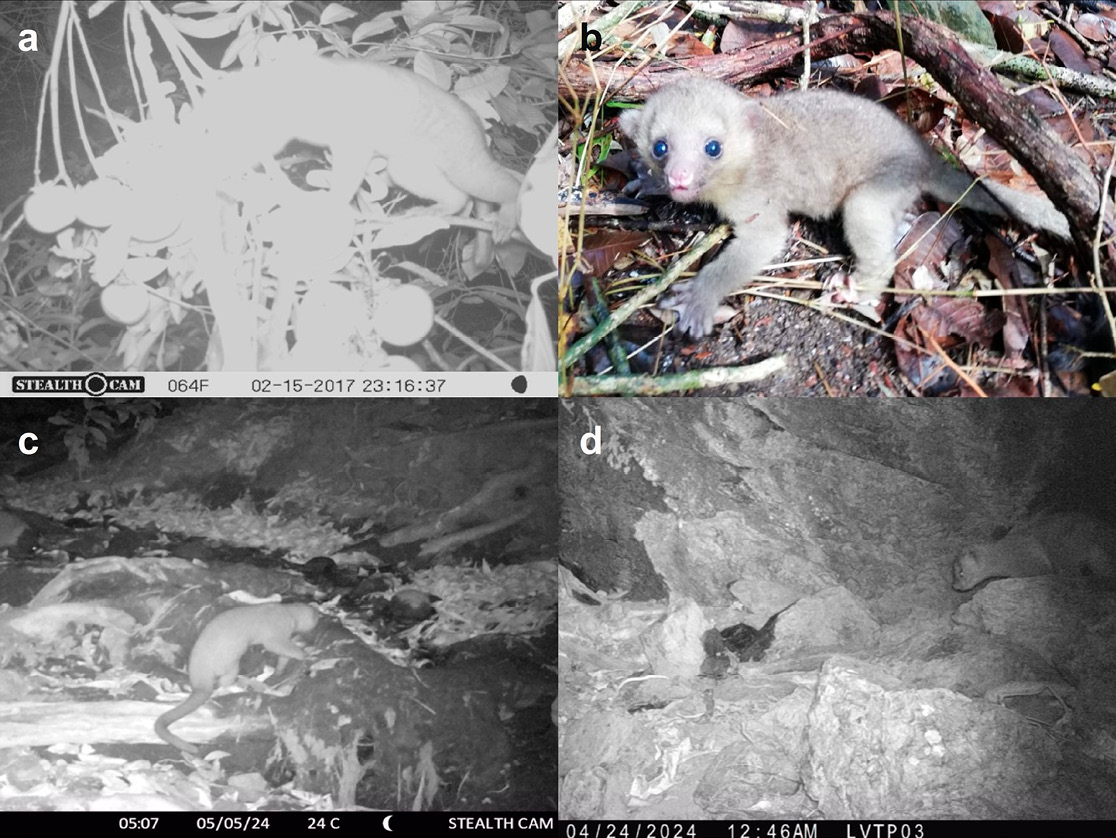

A total of 11 unique coordinates records were examined including field research, camera trap monitoring, observations documented in database portals, literature review and all the compiled records published previously (Monterrubio-Rico et al. 2013) (Table 1).

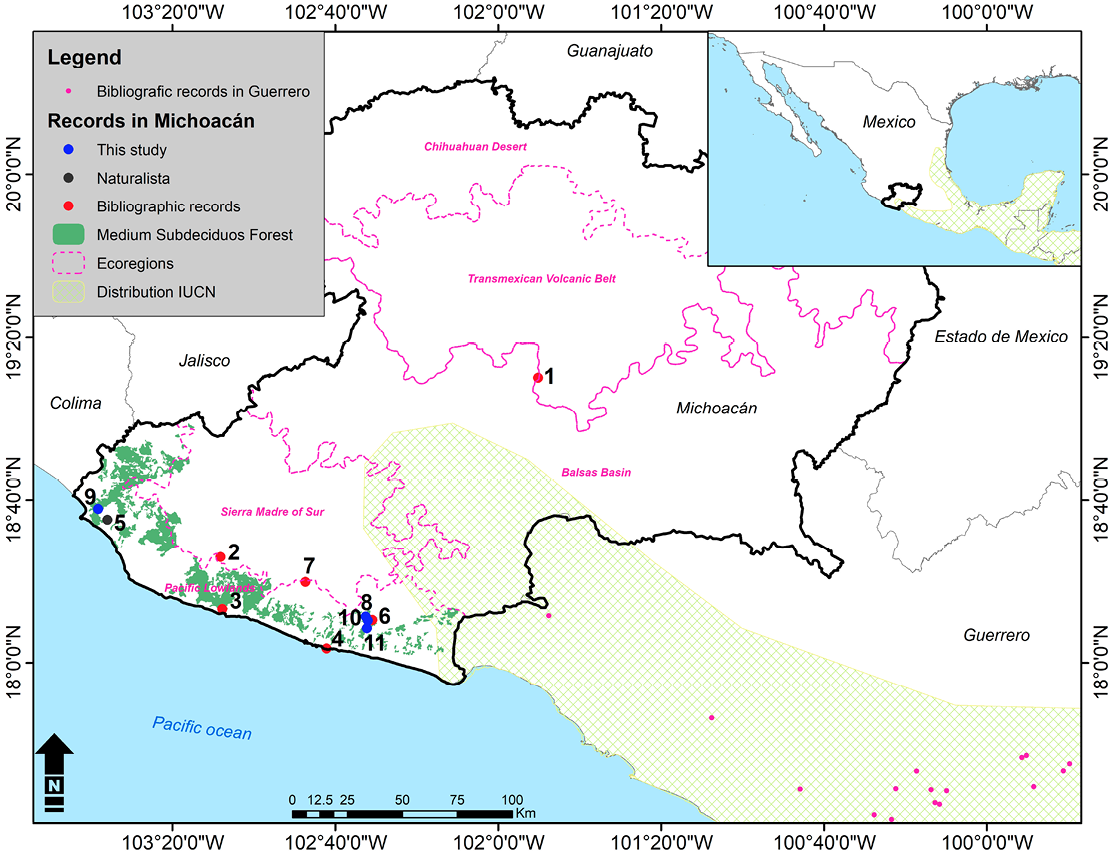

The oldest historic record corresponds to a male specimen collected from the Balsas Basin in the Municipality of Nuevo Urecho housed in the Natural History Museum in London, England, collected by H.H. Smith in 1889; catalog number NHM: 19457 (Arroyo-Cabrales 2010). The coordinates of the record constitute the most interior locality in the state (Record No.1, Figure 1). No other kinkajou record is available from the Balsas region.

During 2013, a comprehensive research note on the Potos flavus status in Michoacán was published (Monterrubio-Rico et al. 2013). It included three compiled historic records (2, 3 and 4; Table 1) from databases and scientific literature (Brand 1961; Sánchez-Hernández and Gaviño de la Torre 1988; Álvarez-Solórzano and López-Vidal 1998). Contemporary records number 6 and 7 from wildlife surveys (Table 1), which included a specimen collected and available at the mammal collection in the Museo de Zoología, Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM, with a preliminary catalog number: MZFC-10737 (Monterrubio-Rico et al. 2013), but now corresponds to the 10748 catalog number (Departamento de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias 2025).

The first contemporary record corresponded to an individual photographed near the Aquila town on December 2009, but was not uploaded to the “iNaturalist” plataform until July 2014 https://mexico.inaturalist.org/observations/738691, by a contributor identified as “Nasua” (Nasua 2025). The record coordinates correspond to northernmost location of the species on the coast (Record 5: Figure 1).

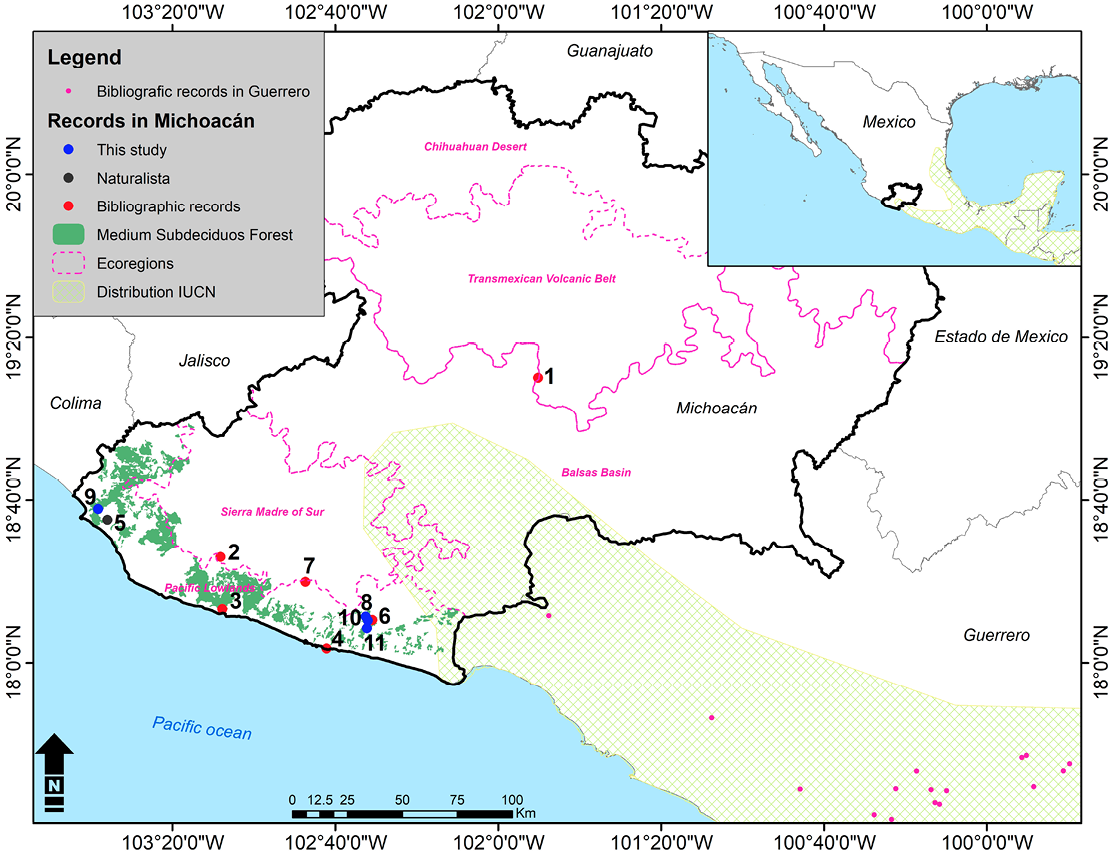

Four of the unpublished reports were obtained by wildlife monitoring efforts carried out during the 2012-2024 period. Record number eight was obtained by placing a camera trap in a zapote prieto tree (Diospyros digyna) to record nocturnal mammals feeding from its fruit. The recorded activity included three kinkajous, an adult male, and an adult female with a juvenile. The feeding behavior was recorded in the same tree since February 12, to March 3, 2017, during 16 different nights (Figure 2a), in the Cayaco locality (Table 1). All recorded feeding behavior events were nocturnal, initiating approximately at 20:30 to 05:00 hr of the following date, with evidence of soncoya fruit (Annona purpurea), and cecropia tree (Cecropia peltata), locally named as “yoyote” consumed by kinkajous as fruit remains were observed on the ground and local settlers confirmed the kinkajou feeding observations.

The three most recent records corresponded to ground activity, which occurred during the driest days with high temperature during the dry season (2019 and 2024 respectively). Record number 9 (the northernmost recent location, Figure 1.) corresponds to a young kinkajou (Figure 2b) abandoned by its mother after being surprised by sunrise laborers. It is assumed that the kinkajous were on their way returning from a nearby spring.

The last two records came from camera traps located to survey faunal activity on the ground, including the use of springs during the dry season (April and May) (Charre-Medellín et al. 2021) (Figures 2c and d). In record 11, the site was monitored by a camera trap programmed in video format during a 34 day-survey period, in which a pair of adult kinkajous were recorded using a water spring during 19 nights (55.8% of survey effort). The kinkajous were hydrating from April 14 to May 16, 2024, and the activity varied among the different nights and hours, the earliest occurred at 20:32, but most commonly initiated around 22:00 hr. Permanence on the spring ranged from three minutes to seven hours.

Although some of the records obtained in this study, correspond to areas near previous reports confirming that the species maintain activity in the area after the publication of Monterrubio-Rico et al. (2013), some records also expand the species observed distribution into Coahuayana municipality (Table 1). In this study, we outlined with higher certainty the kinkajou distribution northern limit in western Mexico, both historically and currently. We hypothesized how the kinkajou distribution in the 19th century included the Balsas Basin (Tierra Caliente), a large tropical dry area of 7,003 km2 (Ihl and Bautista-Zúñiga 2019), as the oldest record available corresponds to Nuevo Urecho, but no other report has been documented from the region. However, it’s also true that research effort and surveys in the region have been limited due to inaccessibility of the rugged terrain in remote areas, and insecurity. In addition, the kinkajous nocturnal and arboreal behavior may limit their detection.

On the other hand, historically, fragments of tropical semideciduous forests, (the kinkajou main habitat in western Mexico) occurred in the most humid areas of the region, and today those areas are now covered by cattle ranches and agricultural areas (Ihl and Bautista-Zúñiga 2019). However, surprisingly kinkajous also wander into dry areas, as in Barranca de Metztitlan Reserve, as a recent individual was observed on a riparian canyon in trees of Prosopis leviagata and Salix humboldtiana, in a landscape with arid scrubland (Hernández-Flores et al. 2018). Therefore, isolated kinkajou groups may likely wonder into the Zicuiran-Infiernillo reserve vast forests, persisting today, as some remote and inaccessible canyons with riparian forests occur adjacent to Guerrero state. Future research should test such hypothesis when additional effort on the region.

This analysis enhances our understanding of the northern distributional limit of the species along the Pacific coast. We can now define this boundary with greater precision near El Ticuiz, in the municipality of Coahuayana, approximately 100 km northwest from the previously recorded limit in El Naranjal (Monterrubio-Rico et al. 2013). Two potential explanations arise from all available kinkajou data, the species historic distribution included the northern tropical forests of the Michoacan coast, but was previously undetected due to limited sampling research effort. A second more speculative explanation is a distributional expansion. It remains unclear the relative importance, use and selection of the remaining patches of tropical semi-deciduous forest by Potos flavus. However, based on INEGI (2021), 143,160 hectares of tropical sub-deciduous forest are still available in Michoacán. Forests available constitute actual potential habitats, and are large enough for the species home range requirements estimated at eight has. (Ford and Hoffmann 1988). Targeted surveys with balanced sampling designs should be conducted across coastal forest fragments along the year to examine seasonal forest use.

Another research topic for the kinkajou presence in the region is how habitat use and selection is influenced by tree species composition, as well as ground water availability. Three camera trap records illustrated area fidelity by the kinkajous, at least during the camera survey period, when a specific fruiting tree or water source were selected. The direct water consumption on the ground is a considerably unusual behavior (Ford and Hoffmann 1988), and the high proportion of surveyed nights detecting their prolonged presence at the water sources may explain the area fidelity observed. Heat stress may explain water spring use. Temperatures of 33°C and above constitute stressful conditions for the species due its limited ability to dissipate heat through evaporation. The documented responses to heat stress in the humid tropics consist in the search for cooler den sites (Ford and Hoffman 1988), making water spring suitable sites to refresh, explaining its presence for several hours. No other reports have evidenced such behavior on Guerrero or the Pacific (Osorio-Rodríguez et al. 2023).

The degree to which kinkajous respond to periods of atypical drought and heat is essential to understand, as the species low metabolic rates are physiologically adapted to stable climatic conditions. In addition, water availability in general for wildlife in the region may experience a decline in the future with climate change. Species populations occurring on the ecological margins of fundamental climatic conditions (temperature and humidity), such as the kinkajou in Michoacán, are considered as relevant in the species responses to climatic changes (Travis and Dytham 2004; Hampe and Petit 2005).

The presence of a viable kinkajou population in Michoacán is important for the entire species range in Mexico. Protected Areas in the region are urgently needed, as forest loss rates have drastically reduced tropical forests (Trejo and Dirzo 2000; Loya-Carrillo and Mas-Caussel 2020), and extensive cattle ranching and extensive agriculture cover 66% of the coastal region and 14% in the Sierra Madre del Sur (Ihl and Bautista-Zúñiga 2019).

Today, no records of kinkajous have been reported for the protected areas of the state, and the coast and Sierra Madre del Sur still present areas that could be considered biodiversity rich. Conserving Potos flavus in Michoacán requires urgent attention to habitat protection and connectivity. As the species shows reliance on water sources and specific fruiting trees, conservation strategies should prioritize the preservation of tropical semi-evergreen forests and the maintenance of ecological corridors that ensure access to these critical resources. Furthermore, the identification and inclusion of potential habitats within protected areas will be essential to strengthen long-term population viability. Collaborative efforts among government agencies, local communities, ONGs and researchers, will be key to safeguarding this ecologically significant species.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the field support provided by Gerardo Soto Mendoza and Jennifer S. Lowry. We are grateful for the continued financial support from the Coordinación de Investigación Científica, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo (UMSNH), the Sectoral Fund for Environmental Research CONACYT-SEMARNAT (Project 2002-C01-00021), and the Mixed Funds CONACYT–State of Michoacán (Project 41168). JFC-M thanks SECIHTI for the postdoctoral fellowship awarded.

Literature cited

Álvarez-Solórzano, T., and J. C. López-Vidal. 1998. Biodiversidad de los mamíferos en el Estado de Michoacán. Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas. Base de datos SNIB2010-CONABIO, proyecto No. P020. México, D. F.

Arroyo-Cabrales, J. 2010. Catálogo de los mamíferos de México en resguardo de The Natural History Museum (London), Inglaterra. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Base de datos SNIB-CONABIO, proyecto DE020. México, D. F.

Ávila-Nájera, D. M. 2006. Patrones de distribución de la mastofauna del estado de Guerrero, México. Tesis de licenciatura. Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México.

Brand, D. 1961. Coalcomán and Motines del Oro. An ex-distrito of Michoacán, México. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague. Institute of Latin American Studies, University of Texas, Austin, Texas, U.S.A.

Departamento de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias (FC-UNAM). 2025. Potos flavus (Schreber, 1774), ejemplar del Museo de Zoología Alfonso L. Herrera (MZFC), Colección de Mamíferos (MZFC-M). En Portal de Datos Abiertos UNAM (en línea). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. https://datosabiertos.unam.mx/FC-UNAM:MZFC-M:10748. Accessed on June 3, 2025.

Emmons, L., and F. Feer. 1997. Neotropical rainforest mammals. 2nd ed. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, U.S.A.

Figueroa, F., and H. T. Arita. 2005. Potos flavus. Pp. 405–408 in Los mamíferos silvestres de México (Ceballos, G. and G. Oliva, eds.). Fondo de Cultura Económica / CONABIO, México.

Ford, L. S., and R. S. Hoffmann. 1988. Potos flavus. Mammalian Species 321:1–9.

Hampe, A., and R. Petit. 2005. Conserving biodiversity under climate change: the rear edge matters. Ecology Letters 8:461–467.

Helgen, K., Kays, R., and J. Schipper. 2016. Potos flavus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T41679A45215631. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T41679A45215631.en. Accessed on 30 June 2025.

Hernández-Flores, S. D., et al. 2018. Registro reciente de la martucha (Potos flavus) para la Reserva de la Biósfera Barranca de Metztitlán y el estado de Hidalgo, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana 34:1–5.

Ihl, T., and F. Bautista-Zúñiga. 2019. Estado actual de la cobertura vegetal y uso de suelo. Pp. 61–65 in La biodiversidad de Michoacán: Estudio de Estado 2. Vol. I. (Cruz-Angón, A., Nájera-Cordero, K. C., and E. D. Malgarejo, eds.). CONABIO. México.

INEGI. 2021. Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de Uso de Suelo y Vegetación, escala 1:250 000, Serie VII. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, México.

Janzen, D. H. 1983. Costa Rican natural history. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

López-Cumatzi, I. L., et al. 2025. Additional dietary records of the arboreal kinkajou (Potos flavus). Therya Notes 6:22–28.

Loya Carrillo, J. O., and J. F. Mass-Caussel. 2020. Análisis del proceso de deforestación en el estado de Michoacán: de lo espacial a lo social. Revista Cartográfica 101:99–117.

Monterrubio-Rico, T. C., et al. 2013. Nuevos registros de la martucha (Potos flavus) para Michoacán, México, que establecen su límite de distribución al norte por el Pacífico. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 84:1002–1006.

Morrone, J. J., et al. 2017. Mexican biogeographic provinces: Map and shapefiles. Zootaxa 4277: 277–279.

Nasua. 2014. Observación en iNaturalistMX: https://mexico.inaturalist.org/observations/738691. Accessed on June 28, 2025.

Nagy-Reis, M., et al. 2020. Neotropical carnivores: a data set on carnivore distribution in the Neotropics.

Osorio-Rodríguez, A. N., et al. 2023. Registros recientes de la martucha (Potos flavus, Carnivora: Procyonidae) en el estado de Guerrero, México, con comentarios de su ocurrencia y amenazas. Mammalogy Notes 9:293–293.

Reid, F. A. 1997. A field guide to the mammals of Central America and Southeast Mexico. Oxford University Press, Oxford, Reino Unido.

Sánchez-Hernández, C., and G. Gaviño de la Torre. 1988. Registros de tres especies de mamíferos para la región central y occidental de México. Anales del Instituto de Biología, UNAM, Serie Zoología 1:477–478.

SEMARNAT (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales). 2010. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010. Diario Oficial de la Federación, 30 de diciembre de 2010, México.

Travis, J. M., and C. Dytham. 2004. A method for simulating patterns of habitat availability at static and dynamic range margins. Oikos 104:410–416.

Trejo, I., and R. Dirzo. 2000. Deforestation of seasonally dry tropical forest: a national and local analysis in Mexico. Biological Conservation 94:133–142.

Wainwright, M. 2002. The natural history of Costa Rican mammals. Zona Tropical, Miami, Florida, U.S.A.

Associate editor: Jorge Ayala Berdón

Submitted: May 24, 2025; Reviewed: September 19, 2025.

Accepted: October 2, 2025; Published on line: December 11, 2025.

DOI: 10.12933/therya_notes-24-223

ISSN 2954-3614

Figure 1. Geographic context of the distribution of martucha (Potos flavus) in Michoacán, Mexico. The numbering corresponds to ID locations in Table 1. Distribution IUCN (Helgen et al. 2016). Bibliographic records in Guerrero (Nagy-Reis et al. 2020; Osorio-Rodríguez et al. 2023).

Figure 2. New records of kinkajou (Potos flavus) in Michoacán, Mexico. IDs correspond to locality numbers in table 1. a) Feeding on a black sapote tree (Diospyros digyna) (ID 8), b) Juvenile (ID 9), c) Drinking from a spring (ID 10), d) Drinking from a spring (ID 11).

Table 1. Records of kinkajou (Potos flavus) in Michoacán, Mexico. Agr = Agriculture, PF = Pine Forest, MSF = Medium Subdeciduous Forest, DF = Deciduous forest, POF = Pine-Oak Forest.

|

ID |

Location |

Longitude |

Latitude |

Elevation |

Municipality |

Vegetation/land use |

Year |

Reference (Source) |

|

1 |

Los Otates |

-101.835876 |

19.167938 |

909 |

Nuevo Urecho |

Agr |

1889 |

Arroyo-Cabrales 2010 |

|

2 |

San José de la Montaña |

-103.135474 |

18.431715 |

794 |

Coalcomán |

PF |

1961 |

Brand 1961 (Literature review). |

|

3 |

Tizupán |

-103.128397 |

18.218728 |

21 |

Aquila |

MSF |

1979 |

Sánchez-Hernández and Gaviño de la Torre 1988 (Literature review) |

|

4 |

El Carrizalillo |

-102.701667 |

18.058333 |

21 |

Lázaro Cárdenas |

DF |

1998 |

Álvarez-Solórzano and López-Vidal 1998 (Online database) |

|

5 |

San Juan de Alima |

-103.59855 |

18.58514 |

99 |

Aquila |

DF |

2009 |

Nasua 2025 (Online databases) |

|

6 |

San José de Los Pinos |

-102.514788 |

18.174446 |

858 |

Arteaga |

POF |

2010 |

Monterrubio-Rico et al. 2013 |

|

7 |

El Naranjal |

-102.788722 |

18.32926 |

792 |

Arteaga |

POF |

2011 |

Monterrubio-Rico et al. 2013 |

|

8 |

Cayaco |

-102.54165 |

18.1881 |

235 |

Arteaga |

MSF |

2017 |

This study (Field survey) |

|

9 |

El Ticuiz |

-103.636265 |

18.629961 |

255 |

Coahuayana |

MSF |

2019 |

This study (Field survey) |

|

10 |

Cayaco |

-102.532781 |

18.171727 |

307 |

Arteaga |

MSF |

2024 |

This study (Field survey) |

|

11 |

Cayaco |

-102.53689 |

18.141016 |

246 |

Arteaga |

MSF |

2024 |

This study (Field survey) |