THERYA NOTES 2025, Vol. 6: 168-173

First record of Perimyotis subflavus in Nuevo León, Mexico with additional ecological notes on hibernacula

Primer registro de Perimyotis subflavus en Nuevo León, México, con notas ecológicas adicionales sobre sus hibernáculos

A. Nayelli Rivera-Villanueva1,2,3, Tania C. Carrizales-Gonzalez1, and Antonio Guzmán-Velasco1*

1Laboratorio de Biología de la Conservación y Desarrollo Sostenible, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. Pedro de Alba, Ciudad Universitaria, C.P. 66455. San Nicolás de los Garza, Nuevo León, México. E-mail: nayelli.riverav@gmail.com (ANR-V); tania.carrigzz@gmail.com (TCC-G), anguve@gmail.com (AG-V).

2Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland P.C. 4072, Australia.

3School of the Environment, The University of Queensland; Brisbane, Queensland P.C. 4072, Australia.

*Corresponding author: anguve@gmail.com

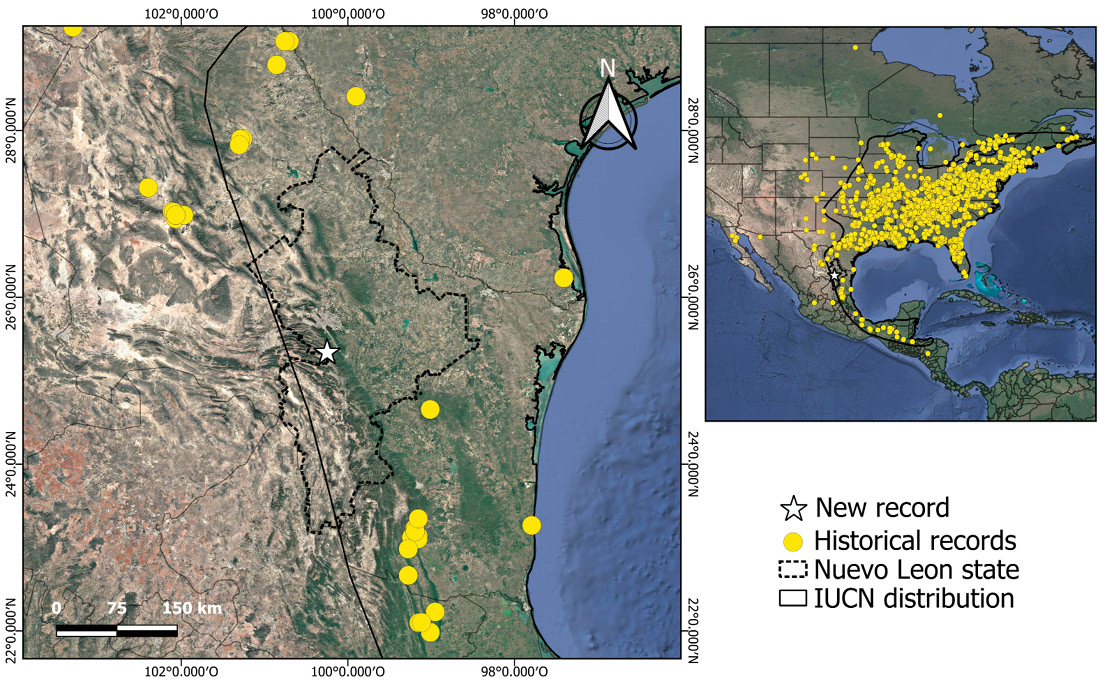

Perimyotis subflavus, is a species that is currently listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List due to the population decline that is causing the White-Nose Syndrome (WNS). However, in Mexico, its ecology and distribution are poorly understood. Despite its distribution in Mexico being mainly in the east, in Nuevo León has never been recorded until now. The individual’s capture was done during a speleologist exploration on March 18th, 2025, in a cave in Laguna de Sánchez, Santiago, Nuevo León. We described the microclimatic characteristics of the roost by measuring the temperature and relative humidity. We also measured individuals fur temperature and roost’s surface temperature where the bat was roosting. Our observation of P. subflavus is the first one in the Nuevo León state. The individual was an adult non-reproductive male in an apparent torpid state. Its fur temperature was 11.1°C, and the roost surface temperature was 13.1°C. The cave’s microclimate at the moment of the capture had a temperature of 12.5°C and a relative humidity of 79.8%. The nearest historical observation of P. subflavus in Tamaulipas state is 146.63 km from our record and 251.08 km from the record in Coahuila state. With our new addition, Nuevo León now has 36 bat species already recorded. The individual was apparently torpid, meaning there are conditions suitable for WNS growth, as it demonstrates that northeast of Mexico could be vulnerable to WNS invasion. Our finding underscores the urgent need to continue studying bat populations in these poorly surveyed regions to anticipate potential threats and establish effective conservation strategies.

Key words: Cave; hibernation; Sierra Madre Oriental; torpor; Vespertilionidae.

Perimyotis subflavus es una especie actualmente clasificada como Vulnerable en la Lista Roja de la UICN debido a la disminución poblacional que ha ocasionado el Síndrome de la Nariz Blanca (SNB). Sin embargo, en México, su ecología y distribución son deficientes. A pesar de que su distribución en México se centra principalmente en el este, en Nuevo León nunca se había registrado hasta la fecha. La captura del individuo se realizó durante una exploración espeleológica el 18 de marzo de 2025 en una cueva en la Laguna de Sánchez, Santiago, Nuevo León. Describimos las características microclimáticas del refugio midiendo la temperatura y la humedad relativa. También medimos la temperatura del pelaje y la temperatura de la superficie del refugio donde el murciélago se encontraba posado. Nuestra observación de P. subflavus es la primera en el estado de Nuevo León. El individuo era un macho adulto no reproductivo en aparente estado de torpor. La temperatura de su pelaje fue de 11.1 °C y la temperatura de superficie del refugio fue de 13.1 °C. El microclima de la cueva en el momento de la captura presentaba una temperatura de 12.5 °C y una humedad relativa del 79.8 %. Nuestro registro amplía la distribución de P. subflavus en 146.63 km desde su observación histórica más cercana en el estado de Tamaulipas y en 251.08 km desde el estado de Coahuila. Discusión: Con nuestra nueva observación, Nuevo León cuenta ahora con 36 especies de murciélagos. El hecho de que este individuo se encontrara en probable letargo, resalta que existen las condiciones propicias para el crecimiento del SNB, ya que demuestra que los hábitats del noreste de México podrían ser vulnerables a su invasión. Nuestro hallazgo subraya la urgente necesidad de continuar estudiando las poblaciones de murciélagos en estas regiones con escasos estudios para anticipar posibles amenazas y establecer estrategias de conservación eficaces.

Palabras clave: Cueva; hibernación; Sierra Madre Oriental; torpor; Vespertilionidae.

© 2025 Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología, www.mastozoologiamexicana.org

The Eastern Pipistrelle bat, Perimyotis subflavus, is a vespertilionid species that can be distinguished from smaller Myotis species by its tricolored hair: dark at the base, lighter and yellowish-brown in the middle, and dark at the tip. The interfemoral membrane is furred in its first third and the calcar is unkeeled (Fujita and Kunz 1984). Perimyotis subflavus is currently listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List due to population declines caused by White-Nose Syndrome (WNS) (Solari, 2018). This disease has drastically increased mortality rates, reaching over 90% in some populations in the USA since its detection in this species in 2013 (Perea et al., 2022).

Its distribution goes from eastern Canada, North and Central United States, and eastern Mexico, following the Sierra Madre Oriental mountain range. It continues down into the tropical lowlands and mountains of northeastern Nicaragua (Fujita and Kunz 1984; Solari, 2018). Despite not being part of its main distribution, P. subflavus can also be found in other regions of Mexico, such as Baja California, Chiapas, Guanajuato, Sonora, and Oaxaca (GBIF 2025). The species can roost in subterranean habitats, trees, and even in artificial places (Fujita and Kunz 1984). Perimyotis subflavus is an obligate hibernator in winter, even under warm conditions (13-18°C) that overlaps with the optimal temperature of the Pseudogymnoascus destructans, the fungus that causes the White-Nose Syndrome (12.5-15.8°C) (Verant et al. 2012; Smith et al. 2021). For this reason, it is crucial not only to record its occurrence but also to gather ecological data about its roosts to identify the potential hibernacula sites vulnerable to the White-Nose Syndrome in Mexico (Rivera-Villanueva et al. 2025). Environmental modeling has projected the region of the Sierra Madre Oriental as the most likely entry point for WNS into Mexico (Gómez-Rodriguez et al., 2022). Identifying the hibernacula and their ecological conditions for one of the most affected species by WNS could help prevent the spread of the disease and mitigate its impacts (Perea et al. 2022). Research on hibernacula has recently advanced, mainly through the work of Ramos-H et al. (2024), who increased the number of torpid bat species known to hibernate in Mexico by over 50% and quadrupled the number of known hibernacula in the country.

However, in order to assess the ecology and vulnerability of this species in Mexico, baseline knowledge of the species’ distribution is first required. Although P. subflavus is primarily found in eastern North America, it has never been recorded in the state of Nuevo León, México. This state is part of the Sierra Madre Oriental mountain range in northeastern Mexico (Jiménez-Guzmán et al., 1998; Wilson et al., 1985). The potential distribution of P. subflavus according to the IUCN includes Nuevo León; however, there is no previous record of the species in the state (Jiménez-Guzmán et al., 1998). Given its distribution across the nearby and ecologically similar states of Coahuila, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas, and Veracruz, the species is also expected to occur in Nuevo León (Fujita and Kunz 1984).

In terms of bat diversity in Nuevo León, 35 species have been recorded in the past, including the endemic Corynorhinus leonpaniaguae (Jiménez-Guzmán et al., 1998; López-Cuamatzi et al., 2024). Here we provide the first record of Perimyotis subflavus in the state, with some ecological observations of its potential hibernacula site, thereby increasing the known bat diversity of Nuevo León to 36 species.

Laguna de Sanchez is a locality in the Santiago municipality in Nuevo León state, Mexico, with pine-oak forest, a yearly precipitation of 643.4 mm, and a mean annual temperature of 10-15°C (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografia, 2024). Laguna de Sanchez is at 1896.9 m.a.s.l, it is part of the Sierra Madre Oriental. Despite the locality being characterized by a Cw1, temperate subhumid climate with an annual temperature between 12°C and 18°C according to Köppen’s climate classification (García 2004), the area has experienced several droughts, leaving the previously permanent lake almost always dry. Fieldwork was part of the expeditions of Laguna de Sanchez Cave Project, which includes more than 130 caves explored in the region (Kennedy 2025).

We recorded the roost microclimate at the time of the finding of P. subflavus. Temperature and relative humidity were taken with a data logger Elitech RC-51H (with an accuracy of ±1º C and ±3.0% relative humidity). We determined the bat to be in an apparent torpid state due to its motionless and cold state (Ramos-H et al., 2024). To gather baseline data on the apparent torpor behavior in this locality, we recorded the bat’s fur temperature while roosting and the surface temperature where the bat was roosting using an infrared thermometer ThermoPro TP30 (with an accuracy of ±1.5°C from -10 to 100°C, and ±2% outside this range) at a distance of approximately 5 cm. The capture was following the guidelines of Sikes and the Animal Care and Use Committee of the American Society of Mammalogists (2016).

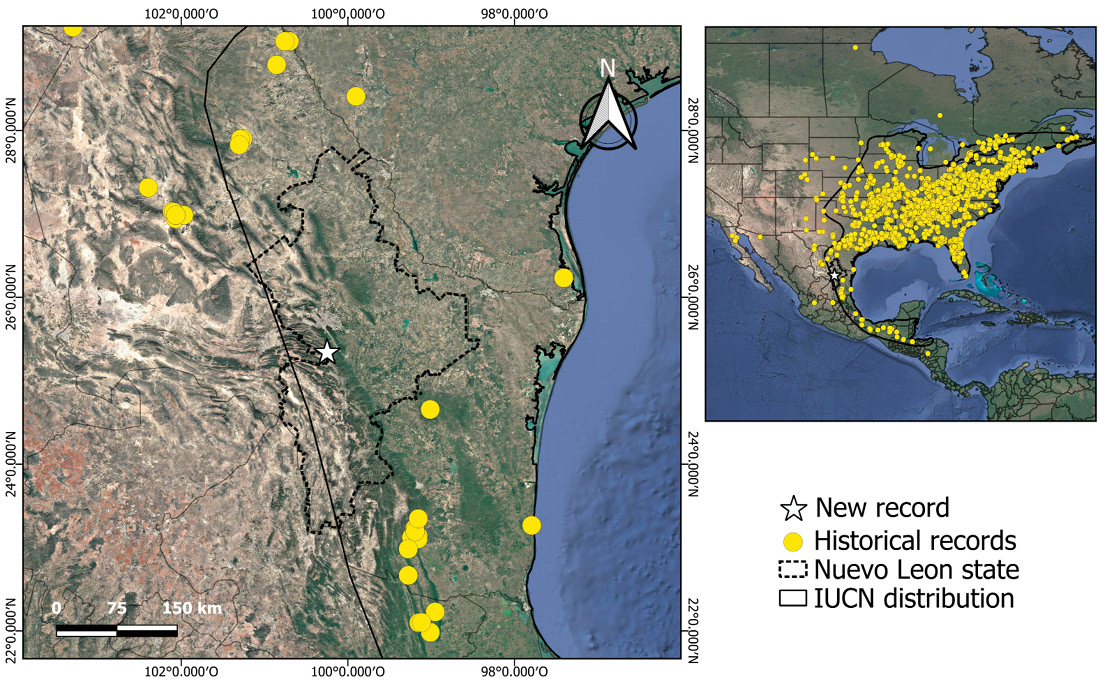

Protective equipment (gloves and a face mask) was used at all times. The bat was gently removed by hand as it began to wake up and was handled quickly to minimize stress. Forearm length was measured with a digital caliper (with an accuracy of ±0.2 mm). It was identified at the moment using the taxonomic keys Medellin et al. (2008). Due to its IUCN Red List category and decreasing population trends, the bat was not included as a collection voucher, but photographs and key measures were taken for identification. Photographs were taken of the uropatagium, dorsal color bands, dental row, full body, and face for documentation. After processing, the bat was released inside the roost. The study followed the requirements of the General Wildlife Federal Law of México (Ley General de Vida Silvestre) under collection permit SPARN/DGVS/09981/23.

To confirm its distribution range, we searched in GBIF (GBIF 2025) records using the scientific name “Perimyotis subflavus”, and searched in the Mammals Collection of the Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas of the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León (UANL). We confirmed the name of collection localities, identified the incorrectly georeferenced records, and verified the identification of preserved specimens when available through digitized scientific collections.

The finding was near the end of the winter season on March 18th, 2025, approximately at 5:00 PM, in a cave located in an area called Mesa Colorada, within Laguna de Sanchez. The cave is located at 25° 20’ 17.628’’N, 100° 14’ 53.667’’W; 2151 m.a.s.l (Figure 1). Its entrance is a small hole on the ground, but the interior opens into a narrow crevice with high ceilings. The cave was inspected as thoroughly as possible, up to the areas accessible to humans, but only one individual was observed. The individual was an adult non-reproductive male in an apparent torpid state, alone in a crevice on a wall at an approximate height of 7 meters (iNaturalist 2025). Its fur temperature was 11.1°C and surface temperature was 13.1°C. The specimen forearm had a length of 31 mm. It was identified by the uropatagium covered with sparse fur and with a calcar unkeeled (Figure 2b). Three color bands (brown-yellow-brown) were also observed (Medellin et al. 2008).

The microclimate of the site where the bat was found had a temperature of 12.5°C and relative humidity 79.8%. From GBIF (2025), we obtained 138 records of P. subflavus from Mexico and 4,576 from the rest of its distribution. Our observation of P. subflavus is the first one in the Nuevo León state and with our new addition, Nuevo León now has 36 bat species, being the 22nd species of Vespertilionidae family in the state. Our record is the first for the state of Nuevo León; the nearest records of P. subflavus are 146.63 km to the East in Tamaulipas state and 251.08 km to the west in Coahuila state.

P. subflavus has been captured in the east of Mexico, including Coahuila, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas, Veracruz, but it is the first time that is recorded in Nuevo León state, probably because of the lack of research in subterranean habitats such as caves, culverts, and mines. Our study site is found in the Sierra Madre Oriental mountain range, which is the region with the most bat captures in the state (Jimenez et al. 1999). There are recent efforts to monitor bat diversity and activity in municipalities near Nuevo León’s capital, Monterrey, such as Santiago, where this finding was made has been conducted. However, its most southern part, such as Doctor Arroyo, General Zaragoza, Mier y Noriega, are the municipalities with the fewest bat captures. We encourage researchers to fill these gaps and increase bat research efforts, not only in subterranean habitats, but also in trees, bridges, and other types of roosts. Considering that P. subflavus also roosts in trees and bridges in other parts of its distribution, such as in the United States, we do not know if its behavior is similar in Mexico (Fujita and Kunz 1984; Newmann et al. 2021). Recent studies record P. subflavus roosting in caves (Ramos-H et al., 2024). Whereas, from the GBIF records, there are no clear patterns of P. subflavus roosting behavior.

This record offers further information on the species’ winter behavior and local distribution, which is relevant given its current conservation status. The fur temperature of the recorded individual was 11.1°C, which is lower than the temperature recorded by Meierhofer et al. (2019) in Texan populations (15.07 ± 2.87ºC). Whereas our substrate temperature (13.1°C) is similar to previously recorded (15.79 ± 3.69ºC; 13 ± 4.4ºC) (Meierhofer et al. 2019; Smith et al. 2021). But has also been recorded in lower substrate temperatures, going from approximately 7 ± 0.5ºC Langwig et al. (2016) to 9.5 ± 1.9ºC (Brack 2007). This means that P. subflavus has a large range of microclimate preferences. Ramos-H et al. (2024) found a strong positive relationship between substrate temperature and fur temperature in Mexican torpid bats.

Although the substrate temperature is not indicative of WNS infection, it has been recorded that P. subflavus uses colder roosting temperatures after WNS infection (Loeb and Winters 2022; Brown et al. 2025). The roosting temperatures of the species overlap with the range of optimal temperature growth of Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Sirajuddin et al. 2025). This means that it is needed to continue researching the microclimate preference of P. subflavus, especially in Mexico, where the WNS is still not recorded. The fact that this individual was found in an apparent torpid state within a roost with environmental conditions suitable for P. destructans growth raises concern, as it demonstrates that northeastern Mexico habitats are vulnerable to P. destructans invasion. Population studies of the eastern pipistrelle bat are of interest for WNS research, as they are considered one of the potential pathways for the entry of WNS into Mexico (Gómez-Rodriguez et al., 2022). Moreover this species is believed to have the ability to undertake regional and long-distance migrations along a latitudinal gradient, and is expected to be more common in males as they can withstand greater metabolic stress by not having to endure the strain caused by pregnancy and lactation (Fraser et al., 2012), which that comes to our attention since the recorded bat was an adult male.

Perimyotis subflavus tends to hibernate singly, not in clusters. Also, during hibernation (winter) tends not to be sex segregated, contrary to the maternity season. And their hibernacula and maternity sites are usually different roosts (Fujita and Kunz 1984). For this reason, we consider our record of only one adult male to be a potential indication that more research needs to be done to understand its ecology. One of the possible explanations for our single recording is that more P. subflavus use the roost but were not found. But to test this hypothesis, the area and the cave need more exploration to understand the behavior of the species in Nuevo León. Our finding underscores the urgent need to continue studying bat populations in these poorly surveyed regions to anticipate potential threats and establish effective conservation strategies.

Acknowledgements

We are very thankful to our speleologist mates such as J. Kennedy, M. Ponce, J. Alfano for their endless support in exploring in the northeast of Mexico, especially to the Laguna Sanchez Project. We also thank the biologist D. Battie and speleologists A. Lu, A. Loh, and M. Denneborg for their field assistance during this record. Also, thanks to Hábitats Resilientes A.C. for their support and the facilities to work in the field with bats and caves.

Brack, V. Jr. 2007. Temperatures and locations used by hibernating bats, including Myotis sodalis (Indiana bat), in a limestone mine: implications for conservation and management. Environmental Management 40:739–746.

Brown, R. L., et al. 2025. Tricolored bat (Perimyotis subflavus) microsite use throughout hibernation. Journal of Mammalogy 106:146–156.

Fraser, E. E., et al. 2012. Evidence of latitudinal migration in tri-colored bats, Perimyotis subflavus. PLoS ONE 7:e31419.

Fujita, M. S., and Kunz, T. H. 1984. Pipistrellus subflavus. Mammalian Species 228:1–6.

García, E. 2004. Modificaciones al sistema de clasificación climática de Köppen (para adaptarlo a las condiciones de la República Mexicana), quinta edición. Instituto de Geografía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Ciudad de México, México.

GBIF Secretariat. 2023. Perimyotis subflavus (F. Cuvier, 1832). En: GBIF Backbone Taxonomy. Checklist dataset. www.gbif.org. Accessed on May 15, 2025.

Gómez-Rodríguez, R. A., et al. 2022. Risk of infection of white-nose syndrome in North American vespertilionid bats in Mexico. Ecological Informatics 72:101869.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 1988. Síntesis geográfica del estado de Nuevo León. INEGI. Aguascalientes, México. In: http://internet.contenidos.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/productos/prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi/productos/historicos/1334/702825927004/702825927004_1.pdf

Jiménez-Guzmán, A., Niño-Ramírez, J. A., and Zúñiga-Ramos, M. A. 1998. Mammals of Nuevo León: distribution and taxonomy. Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. SNIB-CONABIO Database, Project P008. México City, México.

Jiménez-Guzmán, A., M. A. Zúñiga-Ramos y J. A. Niño-Ramírez. 1999. Mamíferos de Nuevo León, México. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. 178 pp.

Kennedy, J. 2025. Laguna caves. In: https://lagunacaves.com/. Accessed on May 15, 2025.

Langwig, K. E., et al. 2016. Drivers of variation in species impacts for a multi-host fungal disease of bats. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 371:20150456.

Loeb, S. C., and Winters, E. A. 2022. Changes in hibernating tri-colored bat (Perimyotis subflavus) roosting behavior in response to white-nose syndrome. Ecology and Evolution 12:e9045.

López-Cuamatzi, I. L., et al. 2024. Molecular and morphological data suggest a new species of big-eared bat (Vespertilionidae: Corynorhinus) endemic to northeastern Mexico. PLoS ONE 19:e0296275.

Medellín, R. A., Arita, H. T., and Sánchez, O. 2008. Identificación de los murciélagos de México: clave de campo. Segunda edición. Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México City, México.

Meierhofer, M. B., et al. 2019. Winter habitats of bats in Texas. PLoS ONE 14:e0220839.

Newman, B. A., Loeb, S. C., and Jachowski, D. S. 2021. Winter roosting ecology of tri-colored bats (Perimyotis subflavus) in trees and bridges. Journal of Mammalogy 102:1331–1341.

Perea, S., et al. 2022. Seven-year impact of white-nose syndrome on tri-colored bat (Perimyotis subflavus) populations in Georgia, USA. Endangered Species Research 48:99–106.

Ramos-H., D., G. Marín, D. Cafaggi, C. Sierra-Durán, A. Romero-Ruíz, y R. A. Medellín. 2024. Hibernacula of bats in Mexico, the southernmost records of hibernation in North America. Journal of Mammalogy 105:823–837.

Rivera-Villanueva, A. N., A. Guzmán-Velasco, J. I. González-Rojas, T. C. Carrizales-Gonzalez, y I. P. Rodriguez-Sanchez. 2025. White-nose syndrome: an emerging disease and a potential threat to Mexican bats. Biología y Sociedad 8:11–22.

Sikes, R. S., and the Animal Care and Use Committee of the American Society of Mammalogists. 2016. Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research and education. Journal of Mammalogy 97:663–688.

Sirajuddin, P., et al. 2025. Winter torpor patterns of tri-colored bats (Perimyotis subflavus) in the southeastern United States. Journal of Mammalogy 106:468–478.

Smith, L. M., et al. 2021. Characteristics of caves used by wintering bats in a subtropical environment. Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management 12:139–150.

Solari, S. 2018. Perimyotis subflavus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018:e.T17366A22123514. In: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/17366/22123514. Accessed on May 15, 2025.

Verant, M. L., J. G. Boyles, W. Waldrep Jr., G. Wibbelt, y D. S. Blehert. 2012. Temperature dependent growth of Geomyces destructans, the fungus that causes bat white-nose syndrome. PLoS ONE 7: e46280.

Wilson, D. E., et al. 1985. Los murciélagos del noreste de México, con una lista de especies. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie) 8:1–26.

Associate editor: Jorge Ayala Berdón

Submitted: May 24, 2025; Reviewed: September 19, 2025.

Accepted: October 2, 2025; Published on line: December 5, 2025.

DOI: 10.12933/therya_notes-24-216

ISSN 2954-3614

Figure 1. Map of the GBIF records of Perimyotis subflavus and our new record in Nuevo León, México showed with a star.

Figure 2. a) and c) Perimyotis subflavus captured to confirm reproductive stage; b) uropatagium covered with sparse fur in the first third of the femoral region; d) The adult non-reproductive male of P. subflavus in a probably torpid state. Photos authoring not disclosed for review.