THERYA NOTES 2026, Vol. 7: 6-10

Fruit consumption by Trachops coffini

(Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) in Guatemala

Consumo de frutos por Trachops coffini

(Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) en Guatemala

Diana Salguero1,2*, Diana Mansilla-García1,2, Lesly E. Sosa3 and Luis A. Trujillo1,2

1Fundación Defensores de la Naturaleza. 18 calle 18-70, zona 12, Calzada Atanasio Tzul, C.P. 01012. Ciudad de Guatemala, Guatemala. E-mail: dianasofisg@gmail.com (DS); mansilladiana24@gmail.com (DM-G); trujillososaluis@gmail.com (LAT).

2Escuela de Biología, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Ciudad Universitaria, zona 12, C. P. 01012. Ciudad de Guatemala, Guatemala.

3Departamento de Biología, Universidad del Valle de Guatemala. 18 avenida 11-95, zona 15, Vista hermosa III. Ciudad de Guatemala, Guatemala. estefaniesosam27@gmail.com (LES).

*Corresponding author

Carnivorous bats in the Neotropics, such as Trachops coffini (Phyllostomidae), are typically considered strict predators of small vertebrates and invertebrates. Nonetheless, isolated reports of frugivory have been reported in some carnivorous phyllostomid bats. Here, we report the first documented case of fruit consumption by T. coffini in Guatemala. This frugivory event was recorded during nocturnal mist-netting surveys conducted in the Selempín Nature Reserve, El Estor, Izabal, Guatemala. Captured individuals were temporarily held in cloth bags, and fecal samples were collected and examined under a stereomicroscope to assess dietary content. On November 23, 2024, three individuals of T. coffini were captured. Seeds of Ficus maxima were recovered from the feces of one individual. This finding provides direct evidence of dietary flexibility in T. coffini and is consistent with previous reports of frugivory in other carnivorous phyllostomid bats, including T. cirrhosus (now restricted to South America), Chrotopterus auritus, and Vampyrum spectrum.

Keywords: Dietary flexibility, frugivory, carnivorous bats, Neotropics, Selempín Nature Reserve.

Los murciélagos carnívoros del Neotrópico, como Trachops coffini (Phyllostomidae), suelen considerarse depredadores estrictos de pequeños vertebrados e invertebrados. No obstante, se han reportado casos aislados de frugivoría en algunas especies de murciélagos carnívoros filostómidos. En este estudio, reportamos el primer caso documentado de consumo de frutos por T. coffini en Guatemala. Este evento de frugivoría fue registrado durante muestreos nocturnos con redes de niebla en la Reserva Natural Selempín, El Estor, Izabal, Guatemala. Los individuos capturados fueron mantenidos temporalmente en bolsas de tela, para recolectar muestras fecales que posteriormente fueron examinadas bajo un estereomicroscopio para determinar restos del contenido alimentario. El 23 de noviembre de 2024 se capturaron tres individuos de T. coffini. Se recuperaron semillas de Ficus maxima de las heces de uno de ellos. Este hallazgo constituye evidencia directa de flexibilidad alimentaria en T. coffini y es consistente con reportes previos de frugivoría en otros murciélagos carnívoros filostómidos, incluyendo T. cirrhosus (ahora restringida a Sudamérica), Chrotopterus auritus y Vampyrum spectrum.

Palabras clave: Flexibilidad dietaria, frugivoría, murciélagos carnívoros, Neotrópico, Reserva Natural Selempín.

© 2026 Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología, www.mastozoologiamexicana.org

Bats exhibit remarkable dietary diversity, encompassing insectivorous, nectarivorous, frugivorous, folivorous, hematophagous, and carnivorous species (Fenton et al. 1992; Simmons and Conway 2003; Kunz et al. 2011; Rodríguez et al. 2023). Within the family Phyllostomidae, carnivorous bats constitute an ecologically distinct group, primarily feeding on vertebrates such as amphibians, birds, reptiles, and other mammals (Gual-Suárez and Medellín 2021). Among these, bats of the genera Trachops, Chrotopterus, and Vampyrum are recognized as specialized predators, although the extent of their dietary plasticity remains poorly understood.

Species of the genus Trachops, particularly T. cirrhosus, have traditionally been described as specialist predators that primarily feed on frogs and large invertebrates, and occasionally on small lizards and mammals (Reid 2009; Barbosa-Leal et al. 2018; Jones et al. 2020). Although the genus is predominantly associated with carnivory, frugivory has been reported in T. cirrhosus from South America and in T. coffini from Costa Rica. These records, based on fecal and stomach content analyses, are limited to observations of fruit ingestion without seed identification, and thus plant consumption in the genus remains rare, poorly documented, and its underlying drivers remain unclear (Gual-Suárez and Medellín 2021). In Guatemala, dietary information on Trachops is particularly limited, with only a single published record to date (Trujillo 2013; Trujillo and López 2014).

To date, there have been no documented records of fruit or seed consumption by the genus Trachops in Guatemala. Therefore, the objective of this note is to describe the first record of frugivory by T. coffini in the country. This observation contributes to the very limited records of plant consumption in Neotropical carnivorous bats, underscoring that such events remain rare and poorly documented.

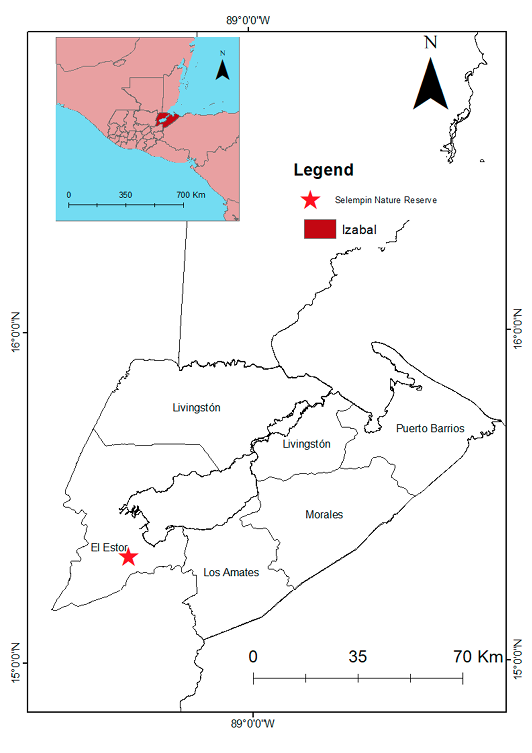

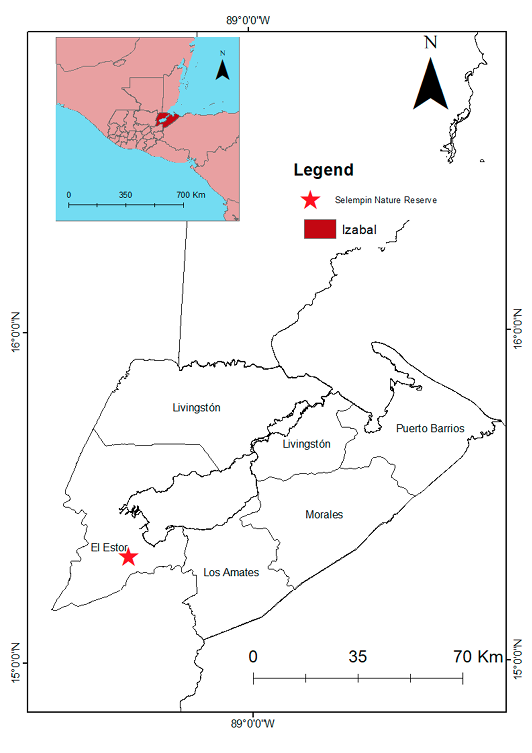

The Selempín Nature Reserve is located in the municipality of El Estor, Izabal department, Guatemala, and encompasses 617 hectares of lowland tropical rainforest (Fundación Defensores de la Naturaleza 2003). Situated within the Caribbean region (15° 19′ 26.98″ N, 89° 23′ 12.01″ W; Figure 1), the reserve features evergreen vegetation characteristic of lowland tropical rainforest, with a canopy dominated by tree species from families such as Moraceae, Fabaceae, Lauraceae, Sapotaceae, Meliaceae, and Rubiaceae, along with palms (Arecaceae) that are highly represented and floristically dominant in humid forests of the region (IARNA-URL 2018). The climate is warm and humid throughout the year, with elevations ranging from 100 to 400 m above sea level (Fundación Defensores de la Naturaleza 2003).

Bats were captured using three 12-meter mist nets set at ground level along natural flyways, including forest trails and the edges of water bodies, following the methodology described by Kunz and Parsons (2009). Mist nets were set up and opened shortly before sunset (approximately 17:30 hr) and remained open for about five hours, with captures checked every 30 minutes.

Morphometric measurements were recorded for each bat, including head and body length (HB), forearm length (FA), ear length (E), tail length (T), hindfoot length (HF), and weight (Wt). All procedures followed the ethical guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists (Sikes et al. 2016), and collection activities were conducted under permits issued by the Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas (CONAP), co-administrators of the protected area (Government Decree No. 93-93).

Species identification followed the field guides and keys of Reid (2009), Medellín et al. (2008), and York et al. (2019), and taxonomic classification was based on Simmons and Cirranello (2025). Recent phylogeographic analyses have demonstrated that the taxon historically identified as Trachops cirrhosus comprises multiple distinct lineages, now recognized as T. coffini, T. ehrhardti, and T. cirrhosus sensu stricto, which exhibit substantial genetic, morphological, and ecological differentiation (da Silva Fonseca et al. 2024). In Mesoamerica, including Guatemala, populations belong to the lineage T. coffini (da Silva Fonseca et al. 2024). Accordingly, we adopt this revised taxonomy and refer to the Central American species as T. coffini.

Subsequently, individuals were placed in separate and previously cleaned cloth bags for up to 30 minutes to obtain fecal samples. Feces were preserved in 70% ethanol and later examined under a stereomicroscope to detect identifiable food remains such as seeds and body parts of arthropods and vertebrates. Seed identification was conducted by comparing specimens with reference images and descriptions from a seed catalogue developed for the study area (FODECYT 68-06; Cajas et al. 2008).

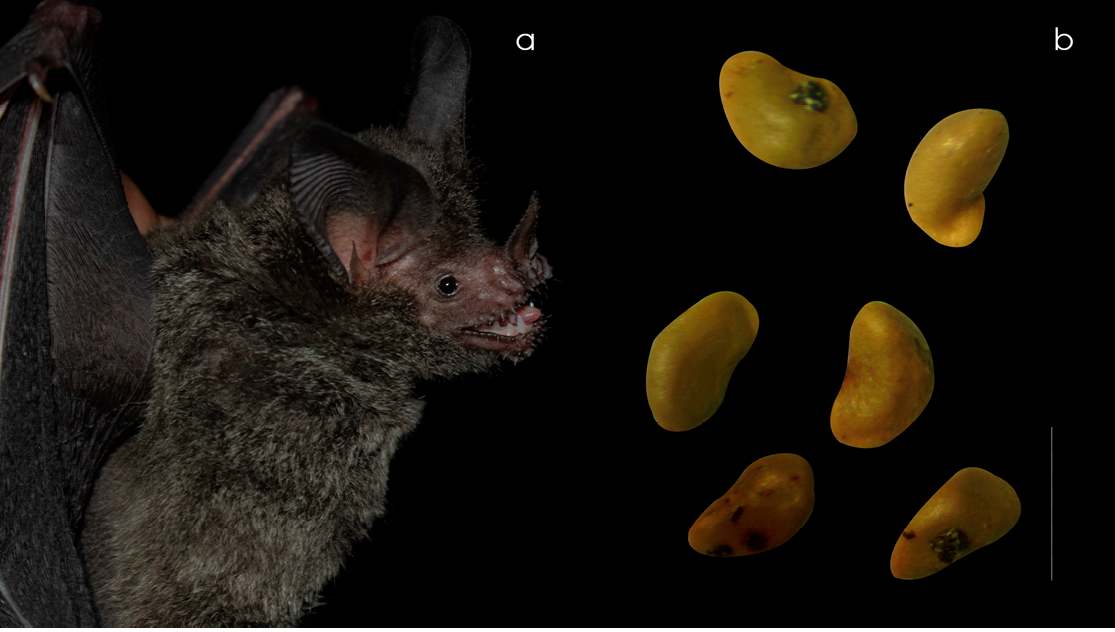

On November 23, 2024, three individuals of T. coffini were captured, and feces from one of them contained six Ficus maxima seeds, providing clear evidence of fruit consumption. The seeds measured 2–3 mm in length, were yellowish, and had a slight fold toward a narrower end that bore a paler coloration, a feature that distinguishes them from other Ficus seeds in the locality (Figure 2). This finding represents the first documented record of F. maxima consumption by this carnivorous species in the region.

The presence of Ficus maxima seeds in the feces of T. coffini, a predominantly gleaning carnivorous bat, provides direct evidence of the inclusion of plant material in its diet and indicates a degree of dietary flexibility. This represents the first documented record of Ficus consumption by a predominantly gleaning carnivorous bat. Other bats belonging to the same subfamily (Phyllostominae), such as Tonatia bidens, have been reported feeding on Ficus, but this species rarely preys on vertebrates and is not considered a true carnivore (Gual-Suárez and Medellín 2021). Although fruit consumption is typically associated with frugivorous bats, other guilds, such as nectarivores, are well known to complement their diets with fruits during certain times of the year (Simmons and Conway 2003; Lobova et al. 2009; Kunz et al. 2011). In contrast, confirmed reports of fruit consumption in carnivorous phyllostomids remain rare and poorly documented (Dobson 1878; Godwin 1946; Navarro 1979; Uieda et al. 2007; Witt and Fabián 2010; Munin et al. 2012; Gual-Suárez 2023).

In the genus Trachops, reports of fruit consumption exist from Costa Rica, Panama, and Brazil, although the plant remains were not identified to taxonomic level (Whitaker and Findley 1980; Humphrey et al. 1983; Bonato et al. 2004). The present finding from Guatemala is the first to confirm the identity of a fruit species consumed by the genus and, together with previous reports, indicates that frugivory is a broader, yet still rarely documented, alternative feeding strategy among carnivorous phyllostomids. The evidence was gathered at the end of the rainy season, when typical prey items for the species are abundant, highly active, and consistently producing acoustic or mechanical cues (Steen et al. 2013).

In other Neotropical carnivorous bats, evidence of fruit consumption remains limited but is increasingly reported (Table 1). Chrotopterus auritus is the best represented, with at least four independent records documenting the consumption of Piper, Cecropia, Solanum, Cestrum, Brosimum, Lucuma, and members of the Araceae, based on fecal samples and food remains from Brazil and Mexico (Uieda et al. 2007; Witt and Fabián 2010; Munin et al. 2012; Gual-Suárez 2023). For Vampyrum spectrum, evidence is scarcer and consists of a recent report from Mexico identifying Solanum sp. (Gual-Suárez 2023), along with historical records from Mexico and Brazil noting fruit rind remains in the digestive tract but without taxonomic identification (Dobson 1878; Godwin 1946; Navarro 1979).

Phyllostomid bats exemplify an exceptional adaptive radiation, occupying one of the most diverse sets of dietary niches among mammals, with diets spanning insects, fish, frogs, lizards, rodents, other bats, birds, fruits, pollen, nectar, and blood (Kalko et al. 1996). Rather than representing a regular dietary component, our finding indicates that carnivorous phyllostomids are capable of exploiting plant resources under certain circumstances (Gual-Suárez and Medellín 2021), although the ecological factors and nutritional significance of this behavior remain poorly understood. While many species show marked specialization on particular food types, multiple studies have shown that, at certain stages of their life history, many species may incorporate alternative resources drawn from across this broad trophic spectrum (Howell and Burch 1974; Reid 2009; Hemingway et al. 2020).

This finding underscores the ecological flexibility of T. coffini as part of a broader behavioral pattern observed across phyllostomids, and highlights the value of documenting rare feeding events for a better understanding of resource use and trophic interactions in Neotropical carnivorous bats.

Acknowledgements

We thank all field personnel, with special recognition to Walter Alvarez and Alfonzo Pérez. We are also grateful to Luis Barrientos, Director of the Bocas del Polochic Wildlife Refuge, and Javier Márquez, Executive Director of Fundación Defensores de la Naturaleza (FDN), along with the entire FDN team, for their invaluable support and unwavering dedication to the conservation of the protected area. We also extend our appreciation to the anonymous reviewers, whose thoughtful comments and suggestions greatly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Literature cited

Barbosa Leal, E. S., et al. 2018. What constitutes the menu of Trachops cirrhosus (Chiroptera)? A review of the species’ diet. Neotropical Biology and Conservation 13 337–346.

Bonaccorso, F. J. 1979. Foraging and reproductive ecology in a Panamanian bat community. Bulletin of the Florida State Museum. Biological Sciences 24:359–408.

Bonato, V., Facure, K. G., and W. Uieda. 2004. Food habits of bats of subfamily Vampyrinae in Brazil. Journal of Mammalogy 85:708–713.

Cajas, J., et al. 2008. Interacciones endozoócoras entre vertebrados y plantas con frutos carnosos en el Refugio de Vida Silvestre Bocas del Polochic, El Estor, Izabal. Proyecto FODECYT 68-06. Anexo 6: Semillas producidas por plantas con frutos carnosos en el RVSBP. Ciudad de Guatemala, Guatemala: Fondo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (FONACYT). Informe técnico, 19 pp.

Cramer, M. J., et al. 2001. Trachops cirrhosus. Mammalian Species 656:1–3.

Da Silva Fonseca B., et al. 2024. A species complex in the iconic frog-eating bat Trachops cirrhosus (Chiroptera, Phyllostomidae) with high variation in the heart of the Neotropics. American Museum Novitates 2024:1–27.

Dobson, G. E. 1878. Catalogue of the Chiroptera in the collection of the British Museum. British Museum (Natural History), London, United Kingdom 567.

Fenton, M. B., et al. 1992. Phyllostomid bats (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) as indicators of habitat disruption in the Neotropics. Biotropica 24: 440–446.

Fundación Defensores de la Naturaleza. 2003. II Plan Maestro 2003-2007: Refugio de Vida Silvestre Bocas del Polochic. Guatemala: Fundación Defensores de la Naturaleza. Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas (CONAP), Ciudad de Guatemala, Guatemala. 103 pp.

Goodwin, G. 1946. Mammals of Costa Rica. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 87:270–473.

Gual-Suárez, F. 2023. Variación estacional y entre grupos sociales de la dieta de Chrotopterus auritus en la selva de Calakmul, Campeche, y su relación con los hábitos de los murciélagos carnívoros del mundo. Tesis Profesional. Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM. 656 pp.

Gual-Suárez, F. and R. A. Medellín. 2021. We eat meat: a review of carnivory in bats. Mammal Review 51:540–558.

Hemingway, C. T., Dixon, M. M., and R. A. Page. 2020. The omnivore’s dilemma: the paradox of the generalist predators. Pp. 239–256, in Phyllostomid bats: a unique mammalian radiation (T. H. Fleming, Dávalos, L. M., and M. A. R. Mello, eds.). University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois.

Howell D. J., and D. Burch. 1974. Food habits of some Costa Rican bats. Revista de Biología Tropical 21:281–294.

Humphrey, S. R., et al. 1983. Guild structure of surface‐gleaning bats in Panama. Ecology 64:284–294.

IARNA-URL (Instituto de Investigación y Proyección sobre Ambiente Natural y Sociedad de la Universidad Rafael Landívar). 2018. Ecosistemas de Guatemala basado en el sistema de clasificación de zonas de vida. IARNA-URL, Ciudad de Guatemala, Guatemala. 122 pp.

Jones, P. L., et al. 2020. Sensory ecology of the frog-eating bat, Trachops cirrhosus. Behavioral Ecology 31:1420–1428.

Kalko, E. K. V., Handley, C. O., and D. Handley. 1996. Organization, diversity, and long-term dynamics of a Neotropical bat community. Pp. 503–553 in Long-term studies in vertebrate communities (M. L. Cody and J. A. Smallwood, eds.). Academic Press, San Diego, California.

Kunz, T. H., et al. 2009. Methods of capturing and handling bats. Pp. 3–35 in Ecological and behavioral methods for the study of bats, 2nd edition (T. H. Kunz and S. Parsons, eds.). Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Kunz, T. H., et al. 2011. Ecosystem services provided by bats. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1223:1–38.

Lobova, T. A., Geiselman, C. K., and S. A. Mori. 2009. Seed dispersal by bats in the Neotropics. Volume 101. New York Botanical Garden, New York, U.S.A.

Medellín, R., et al. 2008. Identificación de los murciélagos de México: Clave de campo. Instituto de Ecología, UNAM, Ciudad de México, México. 78 pp.

Munin, R. L., et al. 2012. Food habits and dietary overlap in a phyllostomid bat assemblage in the Pantanal of Brazil. Acta Chiropterologica 14:195–204.

Navarro, D. L. 1979. Vampyrum spectrum (Chiroptera, Phyllostomatidae) in Mexico. Journal of Mammalogy 60:435.

Reid, F. A. 2009. A field guide to the mammals of Southeast Mexico and Central America. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, New York, USA. 346 pp.

Rodrigues, T. M., et al. 2023. A review of folivory by Neotropical bats. Interfaces Científicas - Saúde e Ambiente 9:29–44.

Ruschi, A. 1953. Morcegos do estado do Espírito Santo. XI Família Phyllostomidae, chaves analíticas para subfamílias, gêneros e espécies, representadas no Estado do Espírito Santo. Boletim do Museu de Biologia Prof. Mello Leitão, Série Zoologia 13:1–18.

Sikes, R. S., and The Animal Care and Use Committee of the American Society of Mammalogist. 2016. Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research and education. Journal of Mammalogy 97:663–688.

Simmons, N. B., and A. L. Cirranello. 2025. Bat species of the world: A taxonomic and geographic database. Version 1.5. . Accessed on: 2025-05-17.

Simmons, N. B., and T. M. Conway. 2003. Evolution of ecological diversity in bats. Pp 493–535 in Bat ecology (T. H. Kunz and M. B. Fenton, eds.). University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Steen, D. A., McClure, C. J. W., and S. P. Graham. 2013. Relative influence of weather and season on anuran calling activity. Canadian Journal of Zoology 91:462–467.

Trujillo, L. 2013. Análisis de nicho trófico de la comunidad de murciélagos (Mammalia: Chiroptera) del Parque Nacional Laguna Lachuá: un enfoque ecomorfológico. Undergraduate thesis, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala.

Trujillo, L., and J. López. 2014. Análisis del nicho trófico de la comunidad de murciélagos del Parque Nacional Laguna Lachuá: un enfoque ecomorfológico. Revista Científica 24:58–70.

Uieda, W., et al. 2007. Fruits as unusual food items of the carnivorous bat Chrotopterus auritus (Mammalia, Phyllostomidae) from southeastern Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 24:844–847.

Whitaker Jr., J. O., and J. S. Findley. 1980. Foods eaten by some bats from Costa Rica and Panamá. Journal of Mammalogy 61:540–544.

Witt, A. A. and Fabián, M. E. 2010. Hábitos alimentares e uso de abrigos por Chrotopterus auritus (Chiroptera, Phyllostomidae). Mastozoología Neotropical 17:353–360.

York H.A., et al. 2019. Field key to the bats of Costa Rica and Nicaragua. Journal of Mammalogy 100:1726–1749.

Associate editor: Cristian Kraker Castañeda

Submitted: May 20, 2025; Reviewed: October 14, 2025.

Accepted: November 25, 2025; Published on line: January 21, 2026.

DOI: 10.12933/therya_notes-24-222

ISSN 2954-3614

Figure 1. Geographic location of the Selempín Nature Reserve in the department of Izabal, Guatemala.

Figure 2. Lateral view of an adult male of Trachops coffini (a), and Ficus maxima seeds collected from the feces of the same individual (b). Scale bar = 3 mm.

Table 1. Documented records of fruit consumption by carnivorous phyllostomid bats in the Neotropics, including the new record in this study. Evidence codes are as follows: FS = fecal sample, DTC = digestive tract content, RS = roost sample (material collected from below bat roosting sites), ND = not determined.

|

Species |

Location |

Fruit item |

Evidence |

Reference |

|

Chrotopterus auritus |

Brasil |

Piper sp., Cecropia sp., Solanum sp., Cestrum sp. |

FS |

|

|

Brasil |

Piper sp. |

DTC |

||

|

Brasil |

ND |

FS |

||

|

Mexico |

Manilkara zapota, Brosimum alicastrum, Araceae sp., Lucuma sp. |

RS |

||

|

Trachops cirrhosus |

Panamá |

ND |

FS |

|

|

Brasil |

ND |

DTC |

||

|

Trachops coffini |

Costa Rica |

ND |

FS |

|

|

Guatemala |

Ficus maxima |

FS |

This study |

|

|

Vampyrum spectrum |

ND |

ND |

DTC |

|

|

Costa Rica |

ND |

DTC |

||

|

Mexico |

ND |

FS |

||

|

Mexico |

Solanum sp. |

DTC |