THERYA NOTES 2025, Vol. 6: 163-167

Density, activity patterns, and habitat selection of Puma

(Puma concolor) in the high-altitude plateaus of Tarapacá, Chile

Densidad, patrones de actividad y selección de hábitat del puma (Puma concolor) en los bofedales de Tarapacá, Chile

Jorge Leichtle*1,2, and Cristian Bonacic3

1Escuela de Medicina Veterinaria, Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad Bernardo O’Higgins, Santiago 8320165, Chile. Email: jleichtle@docente.ubo.cl (JL)

2Doctorado en Conservación y Gestión de la Biodiversidad, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Santo Tomás, Santiago 8370003, Chile.

3Laboratorio de vida silvestre Fauna Australis, Departamento de Ecolosistemas y Medio Ambiente, Facultad de Agronomía e Ingeniería Forestal, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago 7820436, Chile. Email: bona@uc.cl (CB)

*Corresponding author

We investigated the ecology of the puma (Puma concolor) in the high-altitude plateaus of Tarapacá, northern Chile, with a focus on population density, daily activity patterns, and habitat selection. We hypothesized that prey scarcity and human presence would result in low population density, predominantly nocturnal activity, and a preference for shrubland (“tolar”) habitat. Systematic camera-trap surveys were conducted during two seasonal periods in 2012, totaling 1,602 trap-nights. Puma density was estimated using capture-recapture methods based on Maximum Mean Distance Moved (MMDM) and Minimum Convex Polygon (MCP). Activity patterns were analyzed by hour, and habitat selection was assessed using the Ivlev Selection Index and logistic regression. A total of 72 independent detection events were recorded, corresponding to four identified individuals. Density estimates ranged from 0.2 to 0.6 individuals per 100 km²—the lowest reported for Puma concolor in Chile. Eighty percent of detections occurred between 20:00 and 04:59 h, indicating a bimodal nocturnal activity pattern. Shrublands were preferred (Ivlev Index = +0.15), wetlands were avoided (–0.35), and detection probability was higher in areas with over 40% tolar cover. The low population density likely reflects limited wild prey availability and indirect competition with livestock. Nocturnality appears to be a behavioral adaptation to avoid human activity. The broad spatial distribution of detections suggests wide-ranging movements. Although fieldwork was conducted in 2012, ecological conditions have remained relatively stable, supporting the relevance of our findings, despite emerging threats such as infrastructure development and wildlife decline. This study provides essential baseline data on puma ecology in the Tarapacá highlands and supports evidence-based management. We recommend implementing long-term monitoring with telemetry, improving nighttime livestock protection, and conserving tolar corridors to promote puma persistence in high Andean environments.

Keywords: Andean highlands, apex predator, carnivore ecology, human-wildlife conflict, non-invasive monitoring.

Investigamos la ecología del puma (Puma concolor) en el altiplano de la región de Tarapacá, en el norte de Chile, con un enfoque en la densidad poblacional, los patrones de actividad diaria y la selección de hábitat. Se planteó la hipótesis de que la escasez de presas y la presencia humana resultarían en una baja densidad poblacional, actividad predominantemente nocturna y preferencia por hábitats arbustivos de “tolar”. Se realizaron muestreos sistemáticos con cámaras trampa durante dos periodos estacionales en 2012, acumulando un total de 1.602 noches-trampa. La densidad fue estimada mediante métodos de captura-recaptura basados en la Distancia Máxima Promedio de Movimiento (MMDM) y el Polígono Mínimo Convexo (MCP). Los patrones de actividad fueron analizados por hora y la selección de hábitat se evaluó mediante el Índice de Selección de Ivlev y regresión logística. Se registraron 72 eventos independientes de detección, correspondientes a cuatro individuos identificados. Las estimaciones de densidad variaron entre 0.2 y 0.6 individuos por cada 100 km², los valores más bajos reportados para Puma concolor en Chile. El 80 % de las detecciones se produjo entre las 20:00 y las 04:59 h, lo que indica un patrón de actividad nocturna bimodal. Se observó preferencia por el tolar (Índice de Ivlev = +٠.١٥), evitación de bofedales (–٠.٣٥) y una mayor probabilidad de detección en áreas con más del ٤٠ ٪ de cobertura de tolar. La baja densidad poblacional probablemente refleja una disponibilidad limitada de presas silvestres y competencia indirecta con el ganado. La nocturnidad parece ser una adaptación conductual para evitar la actividad humana. La amplia distribución espacial de las detecciones sugiere movimientos de largo alcance. Aunque el trabajo de campo se realizó en ٢٠١٢, las condiciones ecológicas se han mantenido relativamente estables, lo que respalda la vigencia de los hallazgos, a pesar de amenazas emergentes como el desarrollo de infraestructura y la disminución de fauna silvestre. Este estudio proporciona datos de línea base esenciales sobre la ecología del puma en el altiplano de Tarapacá y contribuye al manejo basado en evidencia. Recomendamos implementar monitoreos de largo plazo con telemetría, mejorar la protección nocturna del ganado y conservar los corredores de tolar para favorecer la persistencia del puma en ambientes altoandinos.

Palabras clave: Altiplano andino, conflicto humano-fauna, depredador tope, ecología de carnívoros, monitoreo no invasivo.

© 2025 Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología, www.mastozoologiamexicana.org

DOI: 10.12933/therya_notes-24-215

ISSN 2954-3614

Top predators, particularly large carnivores, play key ecological roles as ecosystem regulators through prey population control and facilitation of ecological processes (Fortuna et al. 2024; Romero-Muñoz et al. 2024). However, these species face global declines due to habitat loss, prey depletion, and human-wildlife conflicts (Torres et al. 2018; Chinchilla et al. 2022).

The puma (Puma concolor), the most widely distributed felid in the Americas, exemplifies these conservation challenges. As solitary territorial carnivores, pumas require extensive home ranges (Elbroch & Kusler 2018; Guerisoli et al. 2019). Neotropical studies report minimum densities of ~0.6 individuals/100 km², reflecting territorial spacing strategies (Guarda et al. 2017; Zanón-Martínez et al. 2023).

In Chile, pumas serve as apex predators across multiple ecosystems (Osorio et al. 2020). Yet ecological knowledge remains scarce for arid northern regions. While density estimates exist for central and southern Chile (Guarda et al. 2017), only Villalobos (2006) reported data for high-altitude plateaus (0.9 ind/100 km² in Arica-Parinacota). This information gap hinders conservation planning in Tarapacá, where puma-livestock conflicts persist (Ohrens et al. 2016). Camera-trapping offers a non-invasive solution for studying this cryptic species across large ranges (Hending 2024; Harley et al. 2024).

Although our fieldwork was conducted in 2012, the ecological insights derived remain relevant due to the long-term stability of high-Andean ecosystems. These environments exhibit minimal interannual variation in vegetation structure and prey composition, providing a consistent ecological baseline. Biomass estimates were derived from bibliographic averages, which may introduce a potential bias in precise seasonal quantification. Nonetheless, these proxies allow for valid spatial comparisons and provide a robust framework for understanding predator-prey dynamics in remote regions.

Given the lack of ecological information for P. concolor in northern Chile, we asked: What is the density of pumas in the high-altitude plateaus of Tarapacá? What are their daily activity patterns, and which habitats do they preferentially use in this landscape? We hypothesized that puma density would be lower than in central and southern Chile due to prey scarcity and human presence, that activity would be predominantly nocturnal, and that shrublands would be preferred over wetlands or grasslands. Based on these questions, this study aimed to: (1) estimate puma density using camera traps, (2) characterize activity patterns, and (3) assess habitat selection in the high-altitude plateaus of Chile.

The research was conducted in Tarapacá’s high-altitude plateaus (3,500–5,000 m), dominated by tolar shrubs (Adesmia spinosissima) and pajonal grasses (Festuca orthophylla). Mean annual temperatures range from 0–10 °C, with 250–300 mm of concentrated rainfall (December–March).

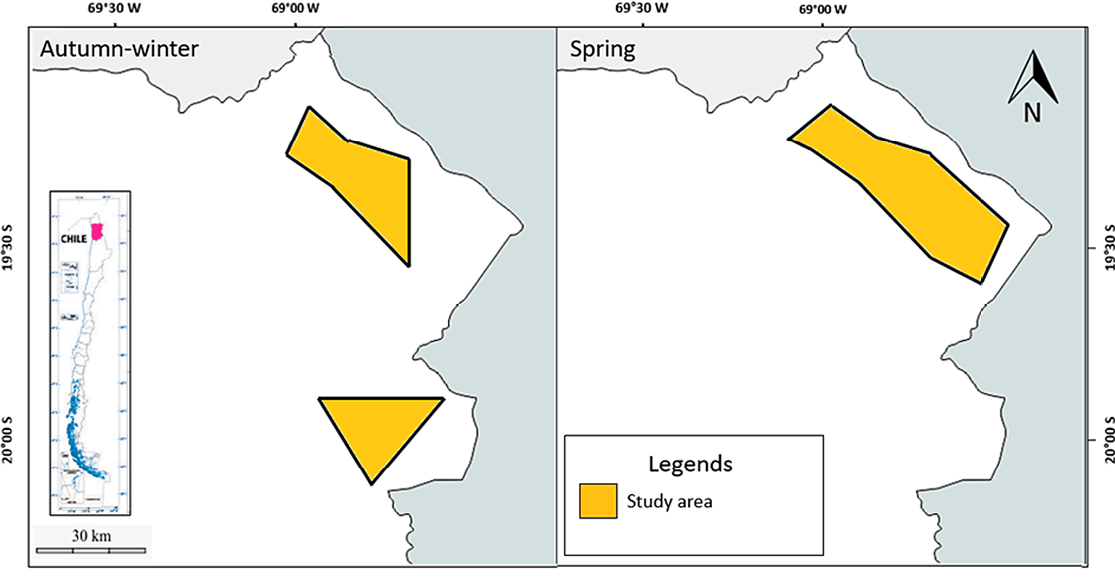

We conducted two surveys in 2012: autumn–winter (April–August) and spring (September–November). Eighteen Bushnell cameras (119455 Trophy Cam XLT) were deployed in a systematic grid (5–10 km spacing), placed along wildlife trails (40–70 cm height, 7 m focal distance). Cameras were set to capture 3-photo bursts (5-min interval), operating continuously with commercial carnivore lures. Individuals were identified via unique pelage patterns. Independent captures required: (1) different individuals in consecutive photos, (2) same individual ≥30 min apart, or (3) same individual at different stations. Density was estimated using Maximum Mean Distance Moved (MMDM) and Minimum Convex Polygons (MCP). Activity patterns were analyzed across four temporal windows, and habitat selection via Ivlev’s Index.

To determine differences in detection probability among habitat types, we conducted a logistic regression analysis using the presence or absence of Puma concolor in each camera station as the binary response variable. The main predictor was vegetation structure, categorized as tolar-dominated (>40% cover) versus other habitats. Odds Ratios (OR) and confidence intervals (95% CI) were computed to assess the strength and significance of habitat associations. Analyses were performed in R using the glm() function (family = binomial), following methodological frameworks used in carnivore ecology (e.g., Harmsen et al., 2011; Kelly et al., 2008).

All statistical analyses were performed using R 4.3.1 (R Core Team, 2013), with bio-statistical procedures executed using the BioestadisticaR package (Femia Marzo et al., 2012).

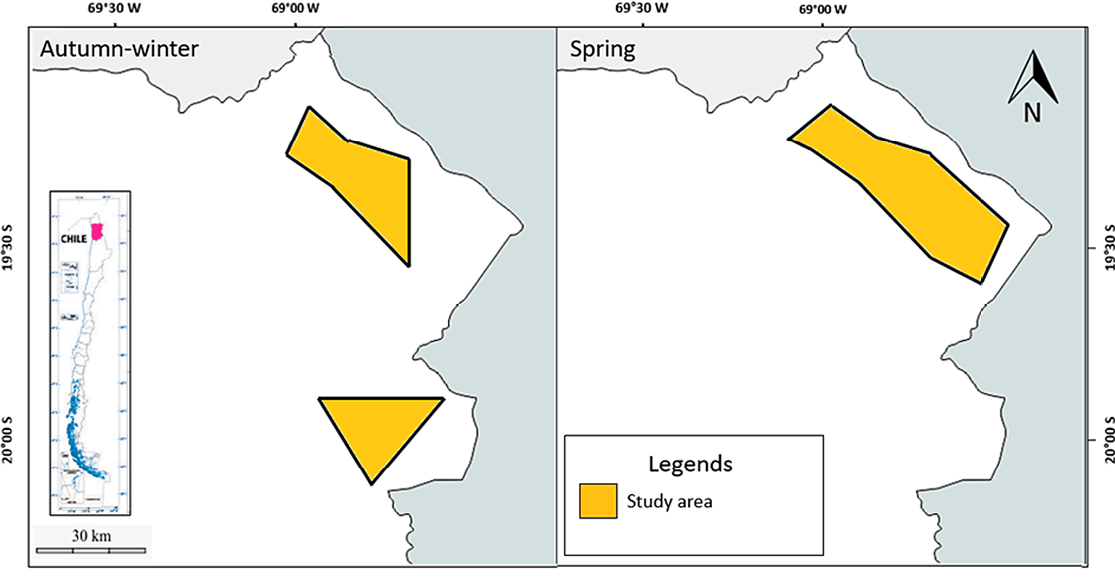

We recorded 72 independent detection events across both seasons: 42 in autumn–winter (0.88 captures/100 trap-nights) and 30 in spring (0.6 captures/100 trap-nights) (Figure 1). These correspond to seven puma detections in the first period and five in the second, totaling twelve records. Four individuals were identified overall (3 adults, 1 subadult), based on pelage and facial markings (Figure 2). Density estimates ranged from 0.5–0.6 ind/100 km² in autumn–winter (707–772 km²) and 0.2–0.4 ind/100 km² in spring (855–1,672 km²) (Table 1).

Table 1. Puma density estimates based on Maximum Mean Distance Moved (MMDM) and Minimum Convex Polygons (MCP) methods in two sampling periods.

|

|

Period 1 (Atumm-winter) |

Period 2 (Spring) |

|

Sampling effort |

792 trap nights |

810 trap nights |

|

Capture success / 100 trap days |

0.88 records |

0.6 records |

|

Puma records |

7 |

5 |

|

Stations with records |

3 |

4 |

|

Identified pumas |

4 |

3 |

|

MMDM |

5.5 km |

8.4 km |

|

Total MMDM area |

707 km² |

1,672 km² |

|

Minimum MMDM density |

0.6 puma/100 km² |

0.2 puma/100 km² |

|

Total MPC area |

772 km² |

855.28 km² |

|

Minimum MPC density |

0.5 puma/100 km² |

0.4 puma/100 km² |

Confidence intervals were not presented for these estimates due to the limited number of spatial recaptures, which prevented robust variance estimation. Given this constraint, densities are reported as minimum values and should be interpreted as a conservative baseline for future monitoring.

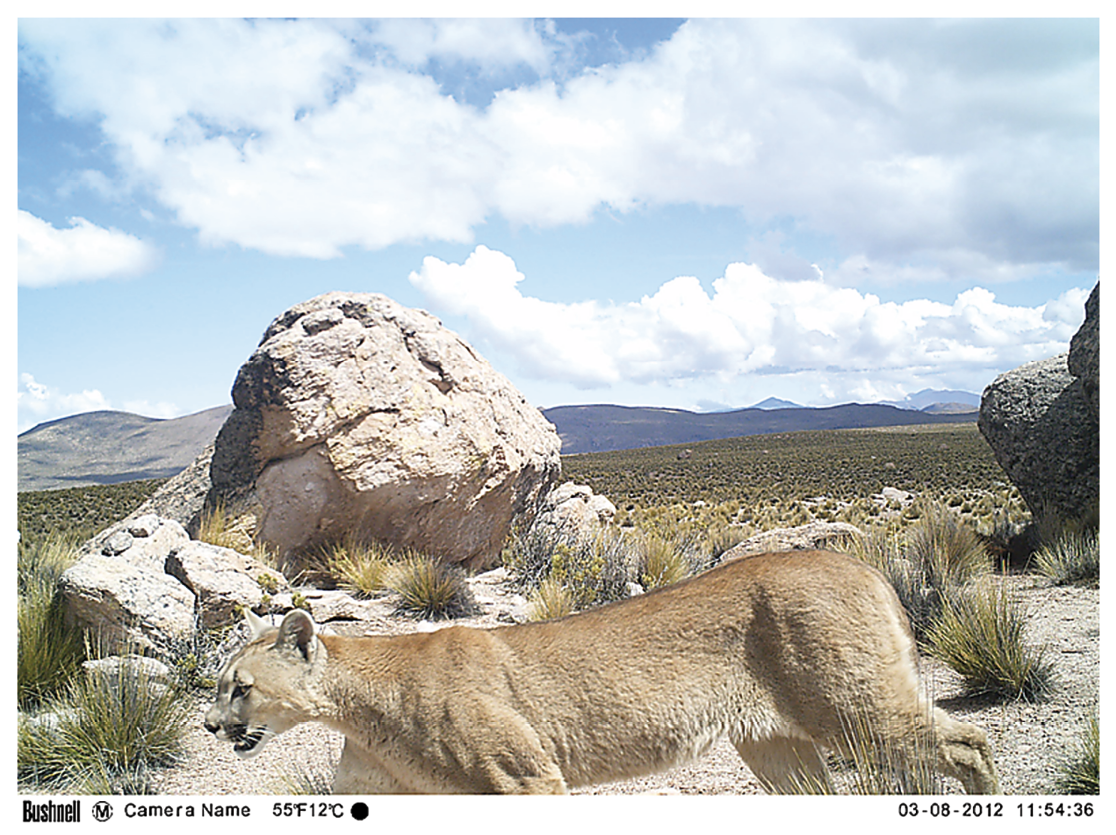

Pumas exhibited strongly nocturnal behavior, with 80% of records occurring between 20:00 and 04:59 h. Activity peaks were concentrated at 21:00–23:00 h (χ² = ١٥.٣, P < ٠.٠١) and ٠٣:٠٠–٠٥:٠٠ h (χ² = ١٢.٧, P < ٠.٠٥), indicating a bimodal pattern centered around midnight and pre-dawn hours. Notably, these intervals fall well outside solar daylight windows, as sunrise during the sampling periods ranged from approximately ٠٦:٣٠ to ٠٧:٠٠ h, and sunset occurred between ١٨:٠٠ and ١٨:٤٥ h. Diurnal (١٣.٣٪) and crepuscular (٦.٦٪) activity was limited (Figure ٣), supporting temporal avoidance of human activity.

“Tolar” shrublands were preferred (50% detections, Ivlev = +0.15), wetlands avoided (–0.35), and grasslands showed neutral selection (–0.02) (Table 2). The probability of detection was significantly higher in areas with >40% tolar cover (OR = 2.3, 95% CI: 1.4–3.8).

Table 2. Habitat preference based on the Ivlev Selection Index.

|

Vegetation Type |

Percentage of Records |

Ivlev Selection Index |

|

Tolar |

50% |

0.15 |

|

Pajonal |

16.50% |

-0.02 |

|

Bofedal |

33.50% |

-0.35 |

Our density estimates (0.2–0.6 ind/100 km²) are Chile’s lowest reported, potentially reflecting: (1) limited wild prey (Vicugna vicugna, Lagidium viscacia), (2) livestock competition, or (3) methodological constraints. Regarding point (2), competition with livestock likely reflects indirect ecological displacement of wild prey, rather than direct interference. The intensive presence of llamas and alpacas in the bofedales may lead to habitat degradation, reduced vegetative cover, and altered resource availability for native species, particularly for herbivores that form the puma’s natural prey base. Additionally, constant human activity associated with pastoralism can suppress wildlife activity and limit prey abundance through behavioral avoidance. These conditions constrain the trophic flexibility of P. concolor, potentially increasing its dependence on domestic livestock and thereby intensifying conflict with local herders.

The pronounced nocturnality (80% activity) likely represents temporal segregation to avoid humans, as observed in other high-conflict areas (Procko et al. 2023). “Tolar” preference reflects its value for hunting, cover, and movement corridors.

Importantly, the fieldwork was conducted in 2012, and while some aspects of the landscape have remained ecologically stable—such as vegetation structure and altiplano livestock presence—there is growing concern over emerging pressures. These include expanding mining infrastructure, declining vicuña populations, and increasing human-livestock interactions at higher elevations. Although long-term trends are not fully documented, anecdotal reports from herders and field teams suggest conservation challenges may be intensifying in the region.

Furthermore, only four of the 18 camera stations recorded puma presence across both seasons. These stations were not spatially clustered but were distributed across the broader sampling polygon (Minimum Convex Polygon), encompassing varied habitat types and elevation gradients. This spatial dispersion supports the interpretation that individuals operate across wide-ranging territories and those detections represent genuine habitat use rather than proximity bias.

However, some limitations must be considered when interpreting these findings. The relatively short sampling period (eight months) may not capture seasonal or interannual variation in density and activity. In addition, the spatial distribution of camera traps was not entirely random, which could bias detection probabilities toward more accessible sites. It is also possible that transient or dispersing individuals were underrepresented due to the stationary sampling design. Finally, the small number of identified individuals (n = 4) and limited spatial recaptures restrict the precision of density estimates, which should be interpreted conservatively.

Despite these limitations, our results provide valuable baseline data and suggest key directions for future conservation efforts. We recommend the implementation of long-term monitoring programs incorporating satellite telemetry to better understand movement ecology and landscape use. In parallel, reinforced nighttime livestock enclosures could help mitigate conflicts with herders, particularly in zones of high nocturnal puma activity. Additionally, preserving and restoring “tolar” shrubland corridors should be prioritized, given their ecological importance as preferred habitats and movement pathways for pumas in the Andean highlands.

Future research should consider expanding spatial coverage and increasing sampling duration across multiple years to improve density estimates and capture potential interannual variability. The use of rotating camera stations and integration of occupancy modeling could further strengthen inference, particularly in low-density or wide-ranging species such as P. concolor.

Although our study is based on data collected in 2012, we emphasize its value as an ecological baseline for the Tarapacá highlands. The region’s relative environmental stability, particularly in vegetation structure and climate, supports the relevance of the findings. However, emerging anthropogenic pressures such as infrastructure development and wildlife population shifts underscore the need for updated information. We highlight the urgency of implementing long-term monitoring to track changes in puma ecology and habitat use. These updated efforts will be essential to evaluate trends over time and support adaptive conservation planning in this vulnerable ecosystem.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Forestry Corporation of Chile (CONAF) and The Agriculture and Livestock Service (SAG) for providing accommodation and assistance in field work within their areas. A special thanks to Jorge Valenzuela, Vinko Malinarich, Omar Ohrens, Mariano De la Maza, Patricio Jaure, Christian Osorio and Carolina Zumaeta for their support in carrying out this project.

Literature cited

Chinchilla, S. et al. 2022. Livestock–carnivore coexistence: moving beyond preventive killing. Animals 12:479.

Elbroch, L. M. and Kusler, A. 2018. Are pumas subordinate carnivores, and does it matter? PeerJ 6:e4293

Femia Marzo, P. et al. 2012. BioestadisticaR: Rutinas de bioestadística en R (Versión 2.0). Universidad de Granada.

Fortuna, CM. et al. 2024. Top predator status and trends: ecological implications, monitoring and mitigation strategies to promote ecosystem-based management. Frontiers in Marine Science 11:1282091.

Guarda, N. et al. 2017. Puma (Puma concolor) density estimation in the Mediterranean Andes of Chile. Oryx 51:263–267.

Guerisoli, MDLM. et al. 2019. Habitat use and activity patterns of Puma concolor in a human-dominated landscape of central Argentina. Journal of Mammalogy 100:202–211.

Harley, D. and Eyre A. 2024. Ten years of camera trapping for a cryptic and threatened arboreal mammal—a review of applications and limitations. Wildlife Research 51:1–12.

Hending, D. 2024. Cryptic species conservation: a review. Biological Reviews 99:1–25.

Ivlev, V. 1961. Experimental ecology of the feeding of fishes. Yale University Press.

Ohrens, O. et al. 2016. Relationship between rural depopulation and puma-human conflict in the high Andes of Chile. Environmental Conservation 43:24–33.

Osorio, C. ET AL. 2020. Exotic prey facilitate coexistence between pumas and culpeo foxes in the Andes of central Chile. Diversity 12:317.

Procko, M. ET AL. 2023. Human presence and infrastructure impact wildlife nocturnality differently across an assemblage of mammalian species. PLOS ONE 18:e0286131.

R Core Tram. 2013. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria.

Romero-Muñoz, A. et al. 2024. Hunting and habitat destruction drive widespread functional declines of top predators in a global deforestation hotspot. Diversity and Distributions.

Villalobos, R. 2006. Ecología del Puma en la región de Arica-Parinacota. Tesis para optar al grado de Magíster en Ciencias Ambientales. Universidad de Chile.

Associated editor: José Manuel Mora Benavides

Submitted: May 3, 2025; Reviewed: July 13, 2025; Accepted: July 15, 2025, Published online: December 6, 2025.

Figure 1. Study area in the high-altitude plateaus of Tarapacá surveyed in autumn-winter and spring seasons.

Figure 2. Adult male puma detected by camera trap, identified through distinctive facial features: a spotted pattern on the left cheek and a pale stripe across the forehead.

Figure 3. Hourly distribution of puma detections from camera traps.