THERYA NOTES 2026, Vol. 7:11-19

Noteworthy acoustic records of Eumops ferox

(Chiroptera: Molossidae) and Mormoops megalophylla (Chiroptera: Mormoopidae) in Mexico

Registros acústicos notables de Eumops ferox

(Chiroptera: Molossidae) y Mormoops megalophylla

(Chiroptera: Mormoopidae) en México

Issachar L. López-Cuamatzi1, Sergio A. Cabrera-Cruz2, and Rafael Villegas-Patraca2*

1Red de Biología y Conservación de Vertebrados, Instituto de Ecología A.C. Carretera antigua a Coatepec 351, El Haya, 91073, Xalapa de Enríquez. Veracruz, Mexico. Email: isachar26@hotmail.com (ILLC)

2Unidad de Servicios Profesionales Altamente Especializados, Instituto de Ecología A.C. Carretera antigua a Coatepec, esq. Camino a Rancho Viejo, 1, Fraccionamiento Briones, 91152, Coatepec. Veracruz, Mexico. Email: sergio.cabrera@inecol.mx (SACC); rafael.villegas@inecol.mx (RVP)

*Corresponding author

Eumops ferox is a molossid previously considered restricted to the Neotropical region south of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt. Mormoops megalophylla is a widespread distributed mormoopid species but restricted in the Baja California Peninsula to Baja California Sur. This note reports notable records of these two species in northern Mexico. By employing Robust Quadratic Discriminant Analysis and Welch’s ANOVA, we analyzed and identified free-flying bat echolocation calls recorded during monthly surveys from January to November 2023 in two regions: Llera de Canales, Tamaulipas, and the Volcanic Complex “Las Tres Vírgenes” in Baja California Sur. Taxonomic identities were determined using frequency and temporal acoustic parameters. A total of 52 echolocation passes from E. ferox were documented in Llera de Canales, Tamaulipas, situated 170 km northwest of its closest previously known record and over 450 km north of its currently recognized distribution range. Additionally, 6 passes of M. megalophylla were identified in “Las Tres Vírgenes”, located 35 km northwest of the nearest prior record. The E. ferox record extends its known range into northeastern Mexico, while the M. megalophylla record marks the northernmost occurrence of the species on the Baja California Peninsula. These findings enhance our knowledge of the distribution of both species in Mexico.

Keywords: Baja California Peninsula; echolocation; insectivorous bats; northernmost record; Tamaulipas.

Eumops ferox es un molósido que anteriormente se consideraba restringido a la región neotropical al sur de la Faja Volcánica Transmexicana. Mormoops megalophylla es una especie de mormópido ampliamente distribuida, pero restringida en la Península de Baja California a Baja California Sur. Esta nota reporta registros notables de estas dos especies en la región norte de México. Mediante el uso de Análisis Discriminante Cuadrático Robusto y el ANOVA de Welch, analizamos e identificamos las llamadas de ecolocalización de murciélagos en vuelo libre, registradas durante muestreos mensuales realizados de enero a noviembre de 2023 en dos regiones: Llera de Canales, Tamaulipas, y el Complejo Volcánico “Las Tres Vírgenes” en Baja California Sur. Las identidades taxonómicas se determinaron utilizando parámetros acústicos de frecuencia y temporales. Un total de 52 secuencias de ecolocalización de E. ferox fueron documentadas en Llera de Canales, Tamaulipas, ubicadas a 170 km al noroeste de su registro más cercano conocido y a más de 450 km al norte de su rango de distribución actualmente reconocido. Adicionalmente, se identificaron 6 secuencias de M. megalophylla en “Las Tres Vírgenes”, situado a 35 km al noroeste del registro previo más cercano. El registro de E. ferox extiende su distribución conocida al noreste de México, mientras que el registro de M. megalophylla corresponde al registro más septentrional de la especie en la Península de Baja California. Estos registros mejoran el conocimiento de la distribución de ambas especies en México.

Palabras clave: Ecolocalización; murciélagos insectívoros; Península de Baja California; registro más septentrional, Tamaulipas.

© 2026 Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología, www.mastozoologiamexicana.org

The effectiveness of bat surveys depends on the sampling method employed (Flaquer et al. 2007). Conventional techniques such as mist nets and harp traps may overlook certain species as foraging strategies, vertical stratification, and echolocation reduce capture success (Berry et al. 2004). Consequently, relying solely on these techniques can underestimate species diversity (MacSwiney et al. 2008).

Since the late 1990s, the analysis of bat echolocation calls has enhanced bat fauna inventories by detecting previously unrecorded species (e. g., Leal-Sandoval et al. 2020; Rodríguez-San Pedro et al. 2022, 2023). With technological advancements and the decreasing cost of ultrasonic recording equipment, the combined use of acoustic monitoring and mist netting has become increasingly common in bat surveys (Zamora-Gutiérrez et al., 2021). Consequently, our understanding of bat diversity and species distribution has improved and continues to be regularly updated (e.g., González-Terrazas et al. 2016; Trujillo et al. 2021).

Through acoustic monitoring, this note reports two notable records in Mexico: Eumops ferox, a molossid bat previously thought to occur only in the Neotropical region south of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (Solari 2019), and Mormoops megalophylla, a widespread distributed mormoopid bat but restricted in the Baja California Peninsula to Baja California Sur (Álvarez-Castañeda 1999; Dávalos et al. 2019).

Acoustic recordings resembling E. ferox and M. megalophylla were obtained in 2023 from monthly surveys (January through November) at Llera de Canales, Tamaulipas, and Mulegé, Baja California Sur, respectively. In Tamaulipas, surveys were carried out near the Guayalejo River (23° 19’ 39.881” N, 99° 1’ 0.469” W) in a Tamaulipan Thorny Scrub with riparian vegetation and crops, under a hot semi-arid climate with summer rains (INEGI 2021). In Baja California Sur, surveys took place around the Las Tres Vírgenes Volcanic Complex (27° 31’ 59.263” N, 112° 33’ 38.372” W) in xerophilous scrubland, featuring a hot desert climate with temperatures of 14–24 °C and annual rainfall below 500 mm (INEGI 2010).

Acoustic surveys were conducted to assess local spatial and temporal patterns of bat activity. At each site, four transects, each 4-6 km in length, were surveyed. Bat activity was recorded for 90 minutes per transect immediately after sunset using an Echo Meter Touch 2 Pro ultrasonic detector (Wildlife Acoustics Inc., Maynard, MA) set to a 256 kHz sampling rate and connected to a Motorola G60S smartphone running Android v11. No frequency or amplitude filters were applied.

Bat echolocation calls were recorded in WAV format and analyzed in BatSound Pro v.3.31 (Pettersson Elektronik AB, Uppsala, Sweden) using a 1024-point FFT, Hamming window, and 95 % overlap, parameters chosen for analytical consistency and user convenience. The shape and structural characteristics of pulses were examined directly in the spectrogram using these settings, along with threshold = 1 and contrast = 2. For some recordings, however, these visualization settings were adjusted up to threshold = 5 and contrast = 4, to improve the clarity of pulse structure. We measured five acoustic parameters commonly used in bat species identification, call duration (Dur), maximum frequency (Fmax), minimum frequency (Fmin), peak frequency (Pkf), and bandwidth (Bw) (Orozco-Lugo et al. 2013; Leal-Sandoval et al. 2020; Ayala-Berdon et al. 2021; Rodríguez-San Pedro et al. 2022). Duration was measured in the oscillogram, beginning at the point where the signal amplitude rose abruptly above the background noise and ending when the amplitude returned to a level comparable to the noise floor, with no subsequent immediate increase (i.e., in signals exhibiting multimodal amplitude peaks resembling a “violin” shape). To visualize the oscillogram, we used the cursor selection tool to define a time window with a width approximately twice the duration of the pulse as displayed in the sonogram. Fmax, Fmin, and Pkf were extracted from the power spectrum (using the same 1024-point FFT, Hamming window, and 95 % overlap). Both Fmax and Fmin were measured at - 10 dB below the peak intensity in the power spectrum (Jensen and Miller 1999), and considering the background noise level present during the specific pulse duration. Pulses were discarded when external noise sources (e.g., insect calls, human noises) interfered with reliable measurement. Bandwidth was defined as the frequency range over which the echolocation pulse occurred and was calculated as the arithmetic difference between Fmax and Fmin.

To identify species recorded in Tamaulipas, we applied Robust Quadratic Discriminant Analysis (rQDA; Todorov and Filzmoser 2009; Tharwat 2016) using the R package rrcov (Todorov and Pires 2007) to build a discriminant model from a training dataset and to assign species identities. The rQDA extends classical QDA by using robust estimators for means and covariances, reducing sensitivity to outliers and assumption violations (Todorov and Filzmoser 2009). The training dataset comprised search-phase echolocation parameters of Eumops ferox recorded in 2020-2023 in La Venta, Oaxaca, Mexico (n = 24, unpublished data), supplemented with mean values from Cuban populations (n = 1, Mora and Torres 2008), and included parameters of sympatric species with similar calls previously recorded in the area: Eumops perotis, Nyctinomops macrotis, Tadarida brasiliensis, and Lasiurus cinereus (Ayala-Berdon et al. 2021; Szewczak 2018; Jung et al. 2014; Guzmán-Soriano et al. 2009; Mora and Torres 2008).

To ensure predictor independence, one pulse per date and site was used in the training data, and Tamaulipas recordings were averaged per pass, treating passes separated by silent gaps or different dates as independent. Principal Component Analysis was applied to reduce multicollinearity, and rQDA was conducted using the first three components of call signatures from E. perotis, N. macrotis, T. brasiliensis, L. cinereus and E. ferox (Oaxaca and Cuba) as training data, excluding PCA-scores of E. ferox from Tamaulipas. Model performance was assessed using accuracy and ROC AUC using the pROC package (Robin et al. 2011) in R (R Core Team, 2025). Species identity for Tamaulipas recordings was then inferred by applying the rQDA model’s posterior probabilities to their PCA-scores.

We assessed each principal component’s contribution to group discrimination using an index based on standardized mean differences. PCA loadings identified the acoustic parameters most linked to the discriminant component, which were then compared between Tamaulipas recordings and other reference species using Welch’s ANOVA with Games-Howell post hoc tests for unequal variances and non-normal data (Delacre et al. 2019; Shingala and Rajyaguru 2015).

For M. megalophylla, we applied the same methodology used for E. ferox in Tamaulipas. The rQDA training dataset included echolocation calls of M. megalophylla (n = 23) and Pteronotus fulvus (n = 40) recorded in La Mancha, Veracruz in 2022 (Echo Meter Touch 2 Pro, unpublished data). Pteronotus fulvus was included because it occurs in Baja California’s Cape Region and its multi-harmonic, quasi-constant, modulated calls resemble those of M. megalophylla (Álvarez-Castañeda ١٩٩٩; Arnaud-Franco et al. 2012; Orozco-Lugo et al. 2013).

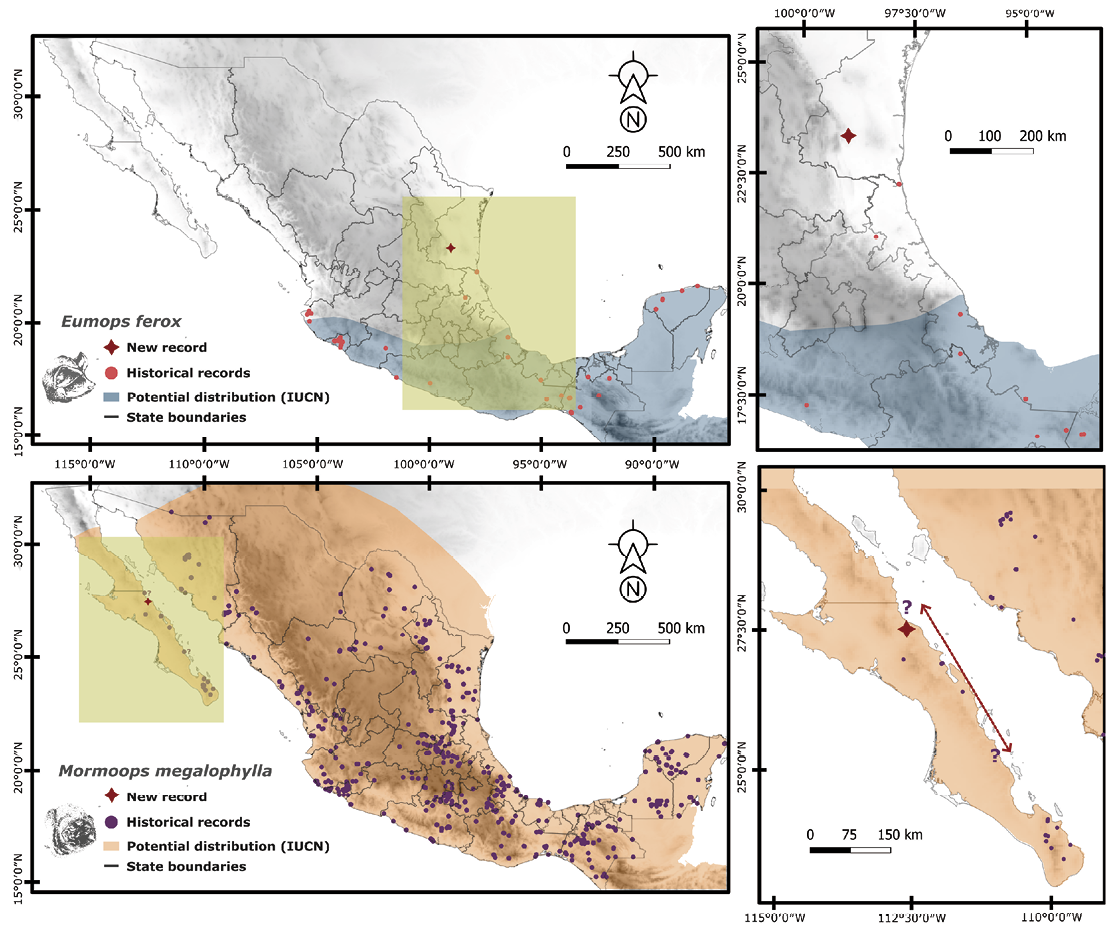

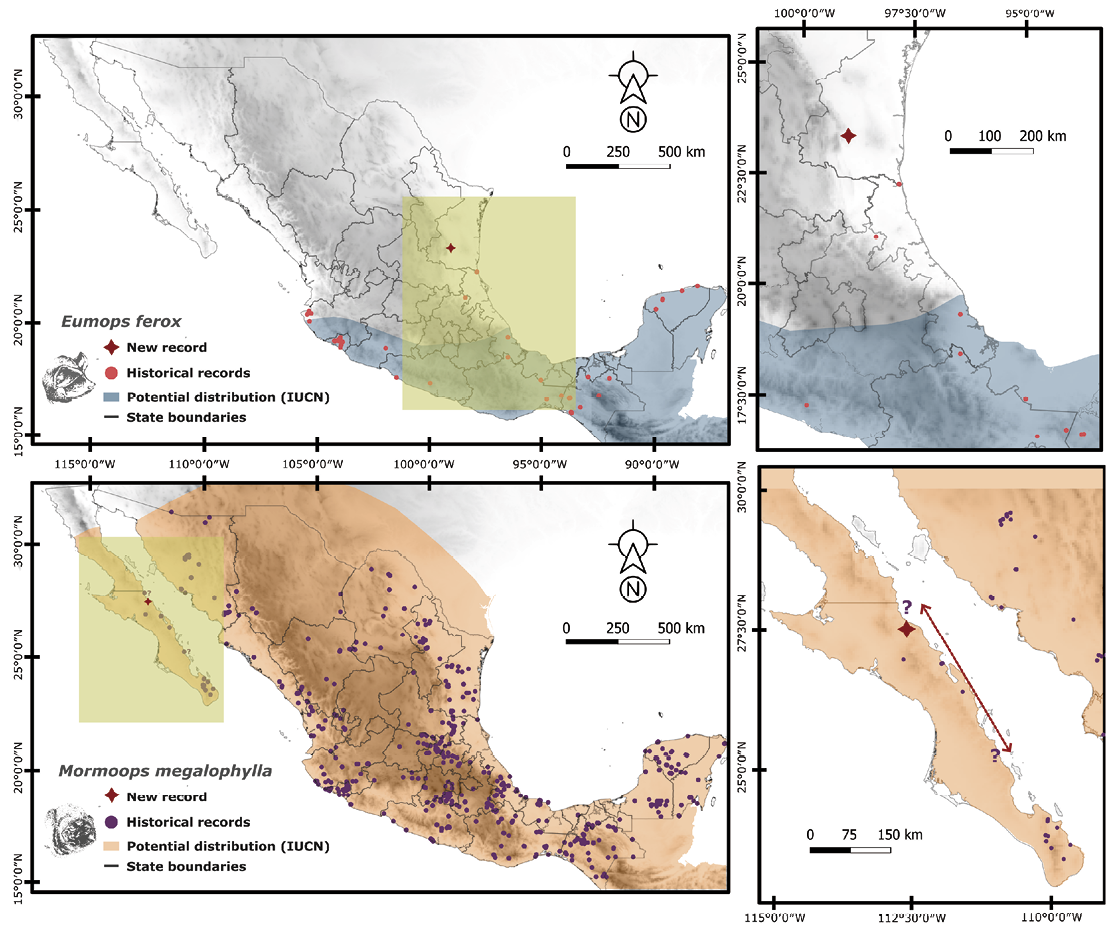

We recorded 52 passes (268 calls) of free-flying Eumops cf. ferox in Llera de Canales, Tamaulipas, ~ 170 km northwest of the nearest previous record (Figure 1). Calls were single-harmonic, quasi-constant frequency (Figure 2a), averaging 16.23 ± 1.06 ms in duration, a minimum frequency of 13.57 ± 0.33 kHz, and 15.69 ± 0.39 kHz peak frequency (Table 1). Recordings occurred multiple times in January, February, July, and August 2023, and activity peaked shortly after sunset and 2-3 h later.

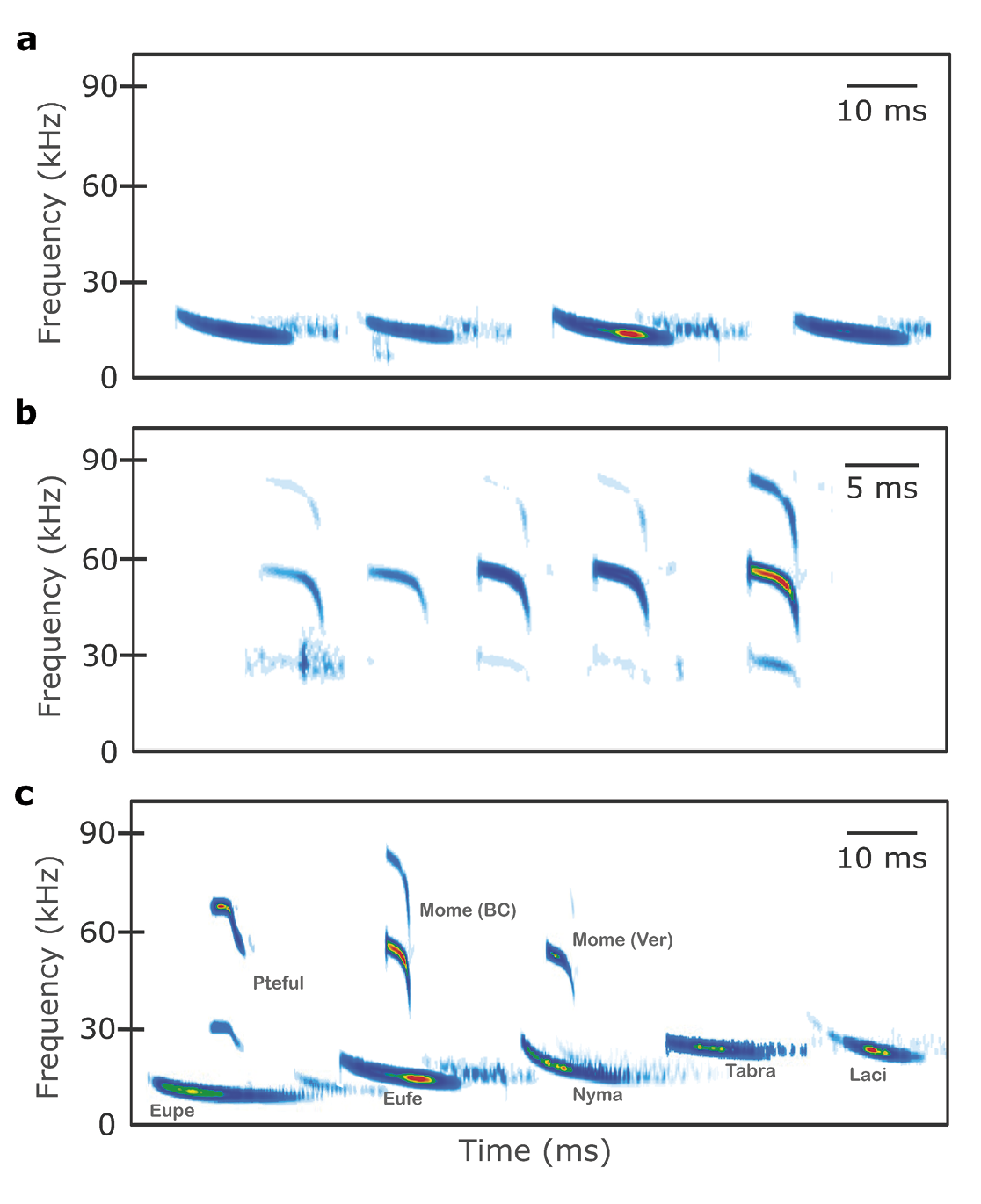

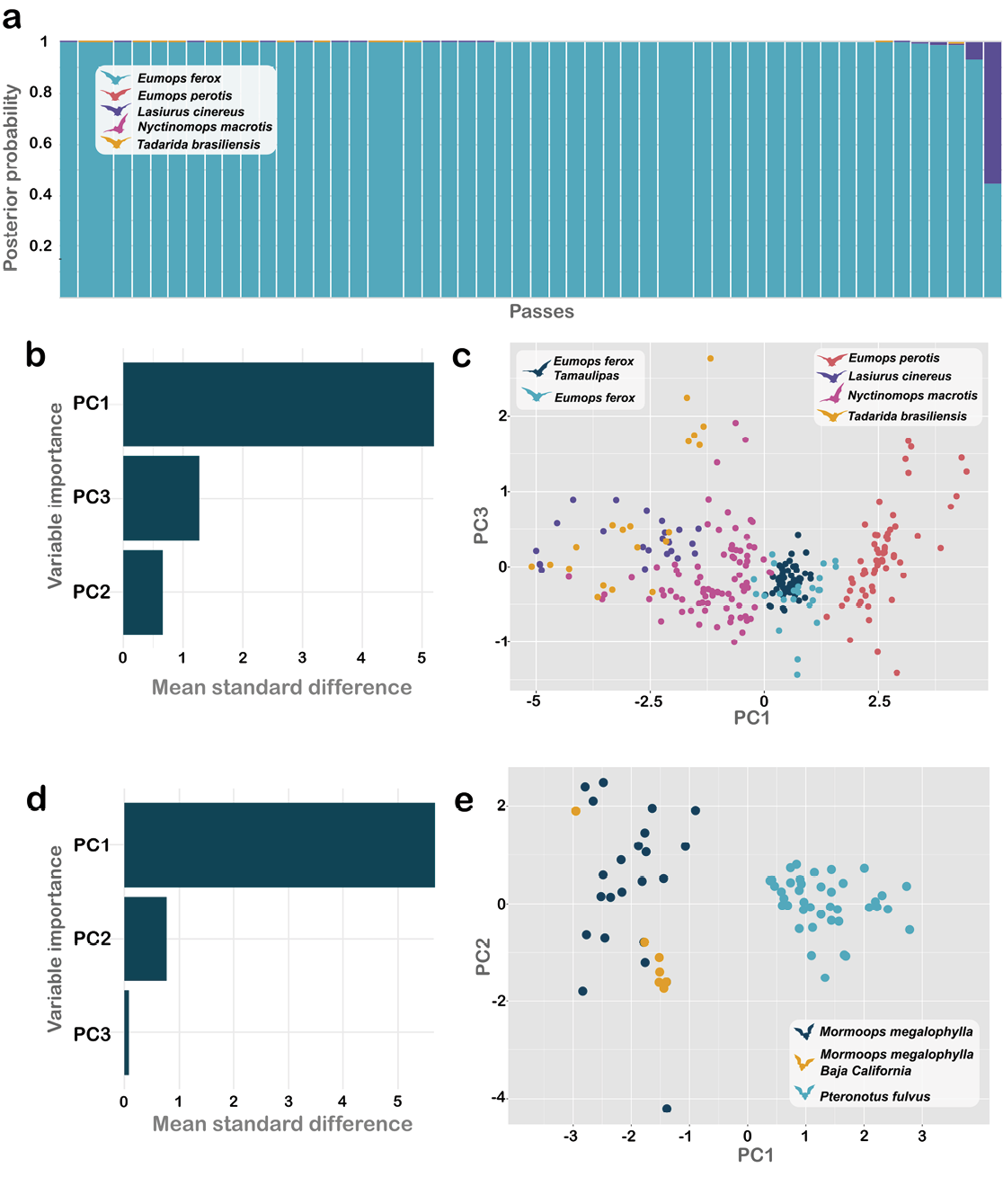

The training dataset violated assumptions of multivariate normality (E = 6.423, P < 0.001) and covariance homogeneity (X² = 396.21, d.f. = 30, P < 0.001), justifying the use of rQDA. The model achieved 93.02 % overall accuracy, with ROC AUC > 0.96 for most species except T. brasiliensis (AUC = 0.68); E. ferox reached 88 % accuracy (AUC = 0.97). Posterior classification assigned 51 passes (98.1 %) from Tamaulipas to E. ferox with high posterior probability (> 0.93) (Figure 3a). The first PC, primarily influenced by Fmin, Fmax, and Pkf, was the most effective for separating E. ferox from other species (Figure 3b,c). Welch’s ANOVA with Games-Howell tests revealed significant differences in these parameters (F = 580.66, d.f. = 5/73.70, P < 0.001 for Pkf; F = 686.41, d.f. = 5/74.25, P < 0.001 for Fmin; F = 294.52, d.f. = 5/75.51, P < 0.001 for Fmax) relative to other aerial-hawking bats, but not compared to E. ferox from the training dataset (Table 2).

For M. megalophylla, we recorded 6 echolocation passes (29 calls) about 55 km north of a previous record in Santa Ana and 35 km northwest of another in Santa Rosalía, Baja California (Figure 1). Calls consisted of a quasi-constant segment followed by a steeply modulated portion; in some cases, a brief initial FM component was present. Up to three harmonics were usually visible, with the second harmonic being the most energetic (Figure 2b). The calls had an average duration of 5.69 ± 0.45 ms, a maximum frequency of 59.05 ± 0.93 kHz, and a peak frequency at 54.4 ± 0.32 kHz (Table 1). Recordings occurred in July, September, and November 2023, 90 min to 2 h after sunset.

The rQDA was applied as the training dataset violated normality (E = 3.351, P < 0.001) and covariance homogeneity (X² = 96.41, d.f. = 12, P < 0.001). The model achieved 100 % classification accuracy and AUC = 1 for both M. megalophylla and P. fulvus. Posterior classification assigned all Baja California passes to M. megalophylla with probability 1. The first PC, primarily influenced by Fmin, Fmax, and Pkf, was the most effective for separating M. megalophylla from Pteronotus fulvus (Figure 3d,e). Welch’s ANOVA (F = 79.251, d.f. = 2/42.18, P < 0.001 for Pkf; F = 1091.9, d.f. = 2/24.57, P < 0.001 for Fmin; F = 467.04, d.f. = 2/20.52, P < 0.001 for Fmax) with Games-Howell post hoc tests confirmed significant differences between Baja California M. megalophylla and P. fulvus (Pkf q = -15.933, P < 0.001; Fmin q = -66.525, P < 0.001; Fmax q = -37.391, P < 0.001), and also with Veracruz M. megalophylla for Pkf, Fmin, and Fmax (Pkf q = 7.148, P < 0.001; Fmin q = -4.737, P < 0.001; Fmax q = 6.39, P < 0.01).

In this note, we report noteworthy records of E. ferox and M. megalophylla in Mexico based on acoustic evidence, extending their known distribution. These findings underscore the importance of ongoing acoustic surveys to document bat diversity in Mexico, particularly in historically underexplored regions with insectivorous bat species. Our models, constructed using Robust Quadratic Discriminant Analysis, successfully distinguished their calls from those of closely related species, strongly suggesting the presence of E. ferox in Tamaulipas and M. megalophylla in northern Baja California Sur.

Echolocation calls of E. ferox from Tamaulipas were clearly distinguished from sympatric aerial-hawking bats (Table 1). While N. macrotis, L. cinereus, and T. brasiliensis emitted higher frequencies (Ayala Berdon et al. 2021; Szewczak 2018), the congener E. perotis produced lower ones (Szewczak 2018; Rodríguez-San Pedro et al. 2023). These differences likely reflect negative allometry between body size and call frequency (Jones 1999; López-Cuamatzi et al. 2020), as E. ferox (Forearm [FA]: 55-63 mm; Body mass [BM]: 34-42 g; Lim 2019a) is larger than L. cinereus (FA: 50-57 mm; BM: 20-35 g; Cláudio 2019) and T. brasiliensis (FA: 36-47 mm; BM: 8-15 g; Lim 2019d), but smaller than E. perotis (FA: 72-83 mm; BM: 52-76 g; Lim 2019b). Interestingly, in comparison with N. macrotis, E. ferox has a similar forearm length but greater body mass (N. macrotis FA: 54-65 mm; BM: 17-34 g; Lim 2019c). Thus, allometry could be a contributing factor; however, it is important to note that this relationship may not apply uniformly across all comparisons, particularly among molossid bats (see Jung et al. 2014), and other factors may also influence the divergence in echolocation call frequencies within our dataset.

The acoustic traits of E. ferox in this study resemble those from Campeche (Guzmán-Soriano et al. 2009), though at slightly lower frequencies. Intraspecific variation in echolocation call parameters is well-documented and often linked to environmental factors (Jiang et al. 2015). For instance, higher frequencies are more prone to atmospheric attenuation under high humidity or wind (Gillam et al. 2009), while lower frequencies are more resilient (Goerlitz 2018). Lower call frequencies of E. ferox in Llera de Canales may reflect the impact of stronger winds (INEGI 2021), similar to observations from La Venta, Oaxaca, another windy site used for training data. Further studies are needed to verify this pattern and its driving factors.

Our multiple records of E. ferox in Llera de Canales, Tamaulipas, suggest its presence in northeastern Mexico. Although surveys covered nearly a full year, the species was detected only in January-February and July-August, indicating a possible seasonal pattern that warrants further year-round monitoring. Previous distribution models (Medellín et al. 2008) suggested the occurrence of E. ferox in the region based on records collected in Tampico, Tamaulipas, in 1923 (FMNH 124224-29), but no additional records existed until now. Combined with historical observations (Figure 1), our findings indicate that the range of E. ferox extends along the Gulf of Mexico slope beyond the limits currently recognized by the IUCN (Solari 2019) (Figure 1).

The shape, multi-harmonic structure, and frequency of M. megalophylla calls in our recordings match previous descriptions from Mexico and the Neotropics (i.e., Orozco-Lugo et al. 2013). However, Games-Howell tests revealed significant differences between Veracruz and Baja California Sur populations, likely reflecting intraspecific geographic variation rather than species-level divergence (Jiang et al. 2015). Despite these differences, both populations remain clearly distinct from P. fulvus.

Previous records of M. megalophylla on the Baja California Peninsula are concentrated in southern Baja California Sur (BCS), including the Cape Region near La Paz and Comondón, as well as two northern BCS locations in Mulegé municipality (Santa Ana, Santa Rosalía, and the municipal head) (Figure 1). A controversial record of M. megalophylla on the Baja California Peninsula concerns a female captured on July 24, 1963, by Jamie Maya and deposited at the University of Arizona Museum of Natural History (UAZ 09941). Although labeled as collected at “Bahía San Carlos, East Coast”, BCS (Bucci 2024), the assigned coordinates (27° 55’ 00.0” N 112° 43’ 00.0” W) fall over water in the Gulf of California (Figure 1). This may represent the northernmost record of the species on the peninsula, but the exact collection site is uncertain. The assigned coordinates were taken from one of two potential locations for Bahía San Carlos in Baja California Sur (Melanie Bucci, curator of the Mammal Collection at the University of Arizona Museum of Natural History, pers. comm.). The second location (25° 16’ 0.001”N, 110° 57’ 0” W), provided by the curator as an alternative (but not shown in either GBIF or VertNet; Bucci, pers. comm.), lies 350 km south of the coordinates assigned to the specimen and 290 km south of our record from the “Las Tres Vírgenes” Volcanic Complex. Given the curator’s acknowledgment of the uncertainty around the location assigned to the UAZ 09941 specimen, reflected in GBIF’s “Georeference verification status” field indicating the need for verification (Bucci 2024), we consider that our record of M. megalophylla in the lowlands of the Volcanic Complex of “Las Tres Vírgenes” represents the most reliable northernmost record of occurrence of this species on the Baja California Peninsula.

Identifying bat species through comparative analyses of echolocation call parameters is a scientific practice that inherently involves some degree of uncertainty regarding taxonomic identity. Acknowledging this uncertainty, we consider that, although our quantitative analyses and the available ecological background on the distribution and ecology of the species discussed in this note support our inferences about these remarkable records, a thorough field exploration of the region is necessary to obtain voucher specimens. Such efforts would confirm the presence of these species and dispel any remaining skepticism. In this sense, our note emphasizes the importance of continued bat monitoring in the region to enhance our understanding of bat diversity and distribution in northern Mexico.

Based on a quantitative analysis of echolocation call parameters, this note reports noteworthy records of E. ferox and M. megalophylla in northern Mexico. The record of E. ferox from Llera de Canales, Tamaulipas, represents the northernmost occurrence of this species and confirms its presence in northeastern Mexico, complementing previous records from Tampico, Tamaulipas. Regarding M. megalophylla, the record presented here constitutes the most reliable and northernmost occurrence of the species on the Baja California Peninsula. Furthermore, our quantitative analysis revealed significant differences in the acoustic parameters of echolocation calls between Baja California and reference data from Veracruz, suggesting the presence of geographic variation that warrants further investigation. The records presented here contribute substantially to understanding the geographic distribution of both species, extending their known ranges and adding new localities. These findings underscore the importance of continued field surveys in northern Mexico and highlight the value of acoustic monitoring for improving bat diversity inventories across the country.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor and the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, which greatly improved the content of this note. The first author thanks C. Alavez Tadeo, M. A. Pulido Alemán, T. Hernández Morales, J. Mendoza, and R. Tepatlán Vargas for their assistance in the fieldwork during the acoustic surveys.

Literature cited

Alvarez-Castañeda, S. T. 1999. Familia Mormoopidae. Pp. 67–76 in Mamíferos del Noroeste de México (Álvarez-Castañeda, S.T., and J. L., Patton, eds.). Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, La Paz, BCS, Mexico.

Arnaud-Franco, G., Álvarez-Cárdenas, S., and P. Cortés-Calva. 2012. Mamíferos de la Reserva de la Biósfera Sierra la Laguna. Pp. 145–161 in Evaluación de la Reserva de la Biósfera Sierra de La Laguna, Baja California Sur (Ortega-Rubio, A., Lagunas-Vázques, M., and L.F. Beltrán-Morales, eds.). Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, SC La Paz, Mexico.

Ayala-Berdon, J., et al. 2021. Random forest is the best species predictor for a community of insectivorous bats inhabiting a mountain ecosystem of central Mexico. Bioacoustics 30: 608–628.

Berry, N., et al. 2004. Detection and avoidance of harp traps by echolocating bats. Acta Chiropterologica 6:335–346.

Best, T. L., Kiser, W. M., and J. C. Rainey. 1997. Eumops glaucinus. Mammalian species 551:1–6.

Bucci, M. 2024. UAZ Mammals. Version 5.4. University of Arizona Museum of Natural History. Occurrence dataset. https://doi.org/10.15468/2swesj accessed via GBIF.org on 2025-01-14. https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/1262401021

Cláudio, V. C. 2019. Lasiurus cinereus [Northern Hoary Bat]. Pp. 876 in Handbook of the mammals of the world. Vol. 9, bats (Wilson, D. E., and R. A., Mittermeier, eds.). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

Davalos, L., et al. 2019. Mormoops megalophylla. In: IUCN 2019. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T13878A22086060. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T13878A22086060.en. Accessed on 21 December 2024.

Delacre, M., et al. 2019. Taking parametric assumptions seriously: Arguments for the use of Welch’s F-test instead of the classical F-test in one-way ANOVA. International Review of Social Psychology 32:1–13.

Flaquer, C., Torre, I., and A. Arrizabalaga. 2007. Comparison of sampling methods for inventory of bat communities. Journal of Mammalogy 88: 526–533.

Gbif.org. 2024a. Eumops glaucinus. (06 November 2024) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.t2t8g3

Gbif.org. 2024b. Eumops ferox. (09 January 2025) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.25mvhq

Gbif.org. 2024c. Mormoops megalophylla. (06 November 2024) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.95vznt

Gillam, E. H., et al. 2009. Bats aloft: variability in echolocation call structure at high altitudes. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 64:69–79.

Goerlitz, H. R. 2018. Weather conditions determine attenuation and speed of sound: Environmental limitations for monitoring and analyzing bat echolocation. Ecology and Evolution 8:5090–5100.

González-Terrazas, T. P., et al. 2016. New records and range extension of Promops centralis (Chiroptera: Molossidae). Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 87:1407–1411.

Guzmán-Soriano, D., et al. 2013. Registros notables de mamíferos para Campeche, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana 29:269–286.

Instituo Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 2010. Compendio de información geográfica municipal 2010 Mulegé Baja California Sur. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/app/mexicocifras/datos_geograficos/03/03002.pd.f. Accessed on 21 December 2024.

Instituo Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 2021. Aspectos Geográficos Tamaulipas. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/app/areasgeograficas/resumen/resumen_28.pd.f. Accessed on 6 December 2024.

Jensen, M. E., and L. A. Miller. 1999. Echolocation signals of the bat Eptesicus serotinus recorded using a vertical microphone array: effect of flight altitude on searching signals. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 47:60–69.

Jiang, T., Wu, H., and J. Feng. 2015. Patterns and causes of geographic variation in bat echolocation pulses. Integrative Zoology 10:241–256.

Jones, G. 1999. Scaling of echolocation call parameters in bats. Journal of Experimental Biology 202:3359–3367.

Jung, K., Molinari, J., and E. K. Kalko. 2014. Driving factors for the evolution of species-specific echolocation call design in new world free-tailed bats (Molossidae). PloS One 9: e85279.

Leal-Sandoval, A., et al. 2020. Acoustic records of Promops centralis (Thomas 1915)(Chiroptera, Molossidae) in corn agroecosystems of northwestern Mexico. Check List 16: 1269–1276.

Lim, B. 2019a. Eumops ferox [Fierced Bonnete Bat]. Pp. 631 in Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9, bats (Wilson, D. E., and R. A., Mittermeier, eds.). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

Lim, B. 2019b. Eumops perotis [Western Bonnete Bat]. Pp. 633 in Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9, bats (Wilson, D. E., and R. A., Mittermeier, eds.). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

Lim, B. 2019c. Nyctinomops macrotis [Big Free-tailed Bat]. Pp. 638 in Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9, bats (Wilson, D. E., and R. A., Mittermeier, eds.). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

Lim, B. 2019d. Tadarida brasiliensis [Brazilian Free-tailed Bat]. Pp. 664 in Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9, bats (Wilson, D. E., and R. A., Mittermeier, eds.). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona, Spain.

López‐Cuamatzi, I. L. et al. 2020. Does body mass restrict call peak frequency in echolocating bats? Mammal Review 50:304–313.

López-Cuamatzi, I. L. 2022. Pteronotus fulvus. Pp. 52–53 in Compendium of Echolocation Calls of Mexican Insectivorous Bats (Ortega, J., Mac Swiney G, M.C., and V., Zamora-Gutierrez, eds.). Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología-CONABIO. Mexico City, Mexico.

MacSwiney, M. C., Clarke, F. M., and P. A. Racey. 2008. What you see is not what you get: the role of ultrasonic detectors in increasing inventory completeness in Neotropical bat assemblages. Journal of Applied Ecology 45:1364–1371.

Medellín, R.A., Arita, T.H., and H. O. Sánchez. 2008. Identificación de los murciélagos de México. Clave de campo (2nd ed.). Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Mexico City, Mexico.

Mora, E. C., and L. Torres. 2008. Echolocation in the large molossid bats Eumops glaucinus and Nyctinomops macrotis. Zoological Science 25:6–13.

Orozco-Lugo, L., et al. 2013. Description of the echolocation ultrasounds of eleven aerial insectivorous bats from a tropical dry forest in Morelos, México. Therya 4:33–46.

R Core Team. 2025. R: A language and environment for statistical. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/.

Rezsutek, M., and G. N. Cameron. 1993. Mormoops megalophylla. Mammalian species 448:1–5.

Ripley, B., et al. 2013. Package ‘mass’. Cran r, 538(113-120), 822.

Robin, X., et al. 2011. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC bioinformatics 12:1–8.

Rodríguez-San Pedro, A., et al. 2022. First record of the Peale’s free-tailed bat Nyctinomops aurispinosus (Peale, 1848)(Chiroptera, Molossidae) from Chile revealed by acoustic surveys, with notes on ecology and distribution. Mammalia 86:321–327.

Rodríguez-San Pedro, A., et al. 2023. Eumops perotis (Schinz, 1821)(Chiroptera, Molossidae): a new genus and species for Chile revealed by acoustic surveys. Mammalia 87:283–287.

Shingala, M. C., and A. Rajyaguru. 2015. Comparison of post hoc tests for unequal variance. International Journal of New Technologies in Science and Engineering 2:22–33.

Solari, S. 2019. Eumops ferox. In: IUCN 2019. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T87994072A87994075. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T87994072A87994075.en. Accessed on 5 December 2024.

Tharwat, A. 2016. Linear vs. quadratic discriminant analysis classifier: a tutorial. International Journal of Applied Pattern Recognition 3:145–180.

Todorov, V., and A. M. Pires. 2007. Comparative performance of several robust linear discriminant analysis methods. REVSTAT-Statistical Journal 5:63–83.

Todorov, V., and P. Filzmoser. 2009. An object-oriented framework for robust multivariate analysis. Journal of Statistical Software 32:1–47.

Trujillo, L. A., et al. 2021. Noteworthy records of bats of the genus Eumops Miller 1906 from Guatemala: first confirmed record of Underwood’s Bonneted Bat, Eumops underwoodi Goodwin 1940 (Mammalia, Chiroptera, Molossidae), in the country. Check List 17:1147–1154.

Zamora-Gutierrez, V., et al. 2021. The evolution of acoustic methods for the study of bats. Pp. 43–59 in 50 Years of Bat Research: Foundations and New Frontiers (Burton K.L, Fenton, M. B., Brigham, R. M., Mistry, S., Kurta, A., Gillam, E. H., Russell, A., and J. Ortega, eds.). Springer. Cham, Switzerland.

Associate editor: Cristian Kraker Castañeda

Submitted: April 21, 2025; Reviewed: December 11, 2025.

Accepted: January 15, 2026; Published on line: February 4, 2026.

DOI: 10.12933/therya_notes-24-225

ISSN 2954-3614

Figure 1. Norteworthy records of Eumops ferox (above) and Mormoops megalophylla (below) from Llera de Canales, Tamaulipas, and the Volcanic Complex Las Tres Vírgenes, Baja California, respectively. Circles represent historical records up to the current study (GBIF.org 2024 a,b,c), while red stars denote new records. The colored areas (blue or orange) indicate the geographic distribution ranges according to the IUCN for E. ferox (Solari 2019) and M. megalophylla (Dávalos et al. 2019). For M. megalophylla, the two potential locations for the previously debated record from Bahía San Carlos, Costa Este (see main text) are marked with question marks and the red arrow indicate the distance between them.

Table 1. Acoustics parameters of echolocation calls for Eumops ferox (Llera de Canales, Tamaulipas) and Mormoops megalophylla (Las Tres Vírgenes Volcanic Complex, Baja California) are highlighted in bold. Calls included in both rQDAs, as well as those from the training dataset, are presented with sample size (n) -indicating the number of calls and the number of passes in parentheses- along with the mean (X̄), standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (CV). Abbreviation: Eumops ferox (Eufe), Eumops perotis (Eupe), Lasiurus cinereus (Laci), Nyctinomops macrotis (Nyma), Tadarida brasiliensis (Tabra), Mormoops megalophylla (Mome), Pteronotus fulvus (Pteful).

|

Eufe (training dataset) |

Eufe Tamaulipas |

Eupe |

Laci |

Nyma |

Tabra |

Mome (training dataset) |

Mome |

Pteful |

||

|

n |

25 |

268(52) |

64 |

23 |

83 |

20 |

23 |

29(6) |

40 |

|

|

Fmax |

X̄ |

17.79 |

19.20 |

12.67 |

30.56 |

23.51 |

30.19 |

55.64 |

59.05 |

71.68 |

|

SD |

1.91 |

0.95 |

1.47 |

5.30 |

3.48 |

3.35 |

3.14 |

0.93 |

1.85 |

|

|

CV |

10.76 |

4.96 |

11.59 |

17.36 |

14.79 |

11.11 |

5.64 |

1.57 |

2.58 |

|

|

Fmin |

X̄ |

13.97 |

13.57 |

10.42 |

22.47 |

18.30 |

23.29 |

42.64 |

38.96 |

57.04 |

|

SD |

0.79 |

0.33 |

1.39 |

1.51 |

0.96 |

1.53 |

5.10 |

0.69 |

1.66 |

|

|

CV |

5.63 |

2.41 |

13.36 |

6.72 |

5.26 |

6.57 |

11.95 |

1.76 |

2.91 |

|

|

Bw |

X̄ |

3.71 |

5.63 |

2.24 |

8.09 |

5.21 |

6.90 |

13.00 |

20.10 |

14.63 |

|

SD |

1.09 |

1.01 |

1.34 |

4.72 |

3.32 |

2.98 |

7.36 |

1.47 |

1.99 |

|

|

CV |

29.26 |

17.89 |

59.83 |

58.33 |

63.79 |

43.23 |

56.63 |

7.31 |

13.61 |

|

|

Pkf |

X̄ |

15.56 |

15.69 |

11.60 |

24.51 |

20.51 |

25.48 |

52.92 |

54.48 |

63.53 |

|

SD |

1.26 |

0.39 |

1.28 |

1.65 |

1.29 |

1.75 |

1.35 |

0.32 |

5.02 |

|

|

CV |

8.08 |

2.46 |

11.03 |

6.74 |

6.26 |

6.86 |

2.54 |

0.59 |

7.89 |

|

|

Dur |

X̄ |

15.00 |

16.23 |

21.06 |

11.09 |

12.24 |

12.04 |

6.94 |

5.69 |

5.88 |

|

SD |

1.95 |

1.06 |

3.59 |

1.53 |

2.55 |

5.60 |

1.50 |

0.45 |

1.50 |

|

|

CV |

13.03 |

6.55 |

17.06 |

13.82 |

20.80 |

46.51 |

21.62 |

7.89 |

||

Table 2. Results of the Games-Howell post-hoc test comparing E. ferox from Tamaulipas with E. ferox from training dataset, and sympatric open-space aerial hawking species presented in Tamaulipas.

|

Pkf |

Fmin |

Fmax |

|||||

|

n |

q |

P |

q |

P |

q |

P |

|

|

Eumops ferox (training dataset) |

25 |

0.732 |

0.995 |

-3.46 |

0.1748 |

4.92 |

0.017 |

|

Eumops perotis |

64 |

34.35 |

< 0.001 |

24.73 |

< 0.001 |

40.84 |

< 0.001 |

|

Lasiurus cinerus |

23 |

-35.77 |

< 0.001 |

-39.55 |

< 0.001 |

-14.42 |

< 0.001 |

|

Nyctinomops macrotis |

83 |

-45.24 |

< 0.001 |

- 58.18 |

< 0.001 |

-15.11 |

< 0.001 |

|

Tadarida brasiliensis |

20 |

-35.11 |

< 0.001 |

- 39.82 |

< 0.001 |

-20.41 |

< 0.001 |

Figure 2. Sonograms of echolocation calls of (a) Eumops ferox recorded in Llera de Canales, Tamaulipas, and (b) Mormoops megalophylla recorded in the Las Tres Vírgenes Volcanic Complex, Baja California Sur. Panel (c) is a composition illustrating sonograms of echolocation calls from various species used as reference for species discrimination analysis based on acoustic parameters. The time between pulses in all panels is compressed and does not represent the actual interval separating them. Abbreviations: Mome (Ver): M. megalophylla from Veracruz; Mome (BC): M. megalophylla from Baja California; Pteful: P. fulvus; Eupe: E. perotis; Eufe: E. ferox; Laci: L. cinereus; Nycma: N. macrotis; Tabra: T. brasiliensis. Sonograms were generated using SonoBat Viewer (free version) with blue contrast settings.

Figure 3. (a) Posterior probability of identity assigned to E. ferox from Tamaulipas based on the rQDA model. Each bar represents a pass. (b) Variable importance, calculated through the mean standard distance of class, for discriminating E. ferox from other open-space aerial hawking species. (c) Scatter plot of the PCA-scores of PC1 and PC3 for E. ferox and other sympatric aerial hawking bat species analyzed in the rQDA. The plot is constructed based on variable importance. (d) Variable importance, calculated through the mean standard distance of class, for discriminating M. megalophylla from P. fulvus. (e) Scatter plot of the PCA-scores of PC1 and PC32for M. megalophylla and P. fulvus analyzed in the rQDA. Similar to E. ferox, the scatterplot is based on variable importance according to the rQDA. In both cases, training and empirical data for E. ferox from Tamaulipas and Oaxaca, as well as M. megalophylla from Baja California Sur and Veracruz, are included.