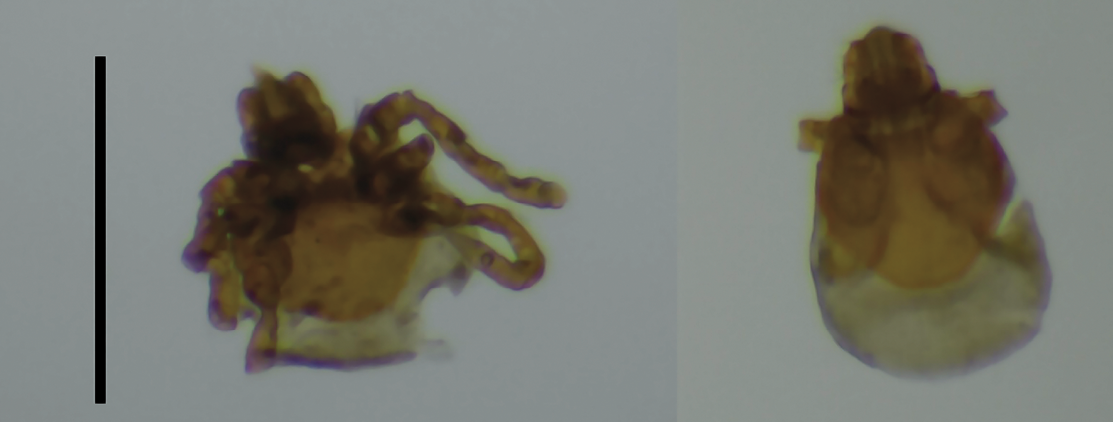

Figure 1. Ventral and dorsal views of Ixodes keiransi larvae specimens (A, B) collected from the intestinal contents of Peromyscus yucatanicus in Yucatan, Mexico. The scale is 600 microns.

Ticks (Parasitiformes: Ixodida) are hematophagous ectopara-sites that are highly diverse and abundant among vertebrates, particularly in small and medium mammals. About 900 species of ticks have been found across different ecosystems. They are divided into three leading families: Ixodidae (hard ticks), Argasidae (soft ticks), and Nuttalliellidae (Boulanger et al. 2019).

Ixodidae includes the Ixodes genus, which includes approximately 266 species (Guglielmone et al. 2023). Many of these are recognized as biological vectors of zoonotic pathogens responsible for several emerging or re-emerging diseases significant to public or animal health (Dantas-Torres et al. 2012; Madison-Antenucci et al. 2020; Aguilar-Tipacamú et al. 2025). Ixodes keiransi is a member of the complex Ixodes affinis, previously referred to as I. cf. affinis, I. near affinis or I. affinis (only in Mexico) (Nava et al. 2023; Rodríguez-Vivas et al. 2023). This tick species occurs in tropical and subtropical regions from Belize, Mexico, and southeastern USA. It has been found specifically in Mexico across Campeche, Chiapas, Hidalgo, Quintana Roo, Veracruz, and Yucatan. It is an ectoparasite that affects many animal hosts, including wildlife, farm animals like cattle and horses, and pets such as dogs and cats (Rodríguez-Vivas et al. 2023, 2024). Adult ticks are primarily associated with members of the Cetartiodactyla and Carnivora, such as cervids and carnivores, while larvae and nymphs tend to infest birds, reptiles, as well as small and medium-sized mammals (Martínez-Ortiz et al. 2019; Flores et al. 2020; Rodríguez-Vivas et al. 2024), including members of the Rodentia (Clark 2004; Harrison et al. 2010; Rodríguez-Vivas et al. 2023).

In the southeastern and northeastern USA, I. keiransi is known to be one of the main vectors that support the enzootic cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto among rodents (Clark 2004; Maggi et al. 2010). Other bacterial genera of public health significance found in I. keiransi include Rickettsia and Bartonella (Martínez-Ortiz et al. 2019; Rodríguez-Vivas et al. 2024).

Wild rodents host several tick species that transmit pathogens, causing emerging or re-emerging zoonotic diseases (Burri et al. 2011; Aguilar-Tipacamú et al. 2025). In Yucatan, some rodents had been identified as hosts of certain pathogenic microorganisms transmitted through biological vectors like ticks, lice, and fleas (Panti-May et al. 2015; Torres-Castro et al. 2018; Panti-May et al. 2021; Arroyo-Ramírez et al. 2023). Peromyscus yucatanicus (Mexican deer mouse) is a rodent endemic species distributed throughout the Yucatan Peninsula, Guatemala, and Belize (MacSwiney-G et al. 2012). This species inhabits various environments, ranging from well-preserved ecosystems to anthropogenically altered areas (Zaragoza-Quintana et al. 2022).

On the other hand, some elements from the diet of P. yucatanicus captured in Mexican tropics (Zaragoza-Quintana et al. 2022) were described. Notably, this is the first international record of tick ingestion by P. yucatanicus.

In a study to identify the helminth fauna of small rodents from the Yucatan Peninsula, we examined the gastrointestinal contents of wild rodents captured in Panabá and Tekax, Yucatan. Characteristics of the study sites are described in Yeh-Gorocica et al. (2024). Briefly, Panabá (grassland landscape) and Tekax (forest with secondary vegetation landscape) have a warm and subhumid climate throughout the year, with two defined climatic seasons (rainy and dry).

During the examination of the gastrointestinal content of 104 small rodents, two partially digested tick larvae (Figure 1) were collected from the gastrointestinal contents of an adult male P. yucatanicus captured at the Panabá site in July 2023. These were preserved in 96% ethanol and stored at -25°C until used. The capture and extraction of rodents were conducted with permission from the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) of Mexico (documents: SPARN/DGVS/06447/22 and SPARN/DGVS/09663/23). This study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of the Autonomous University of Yucatan (official document: CB-CCBA-D-2022-004).

Genomic DNA was extracted from each specimen using Chelex 100 resin® solution (Bio-Rad®, United States of America) as described by Grostieta et al. (2024). To identify the tick species, a fragment of 400 bp of the mitochondrial 16S-rDNA gene was amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), following the criteria outlined by Norris et al. (1996) and the primers 16S+ (CTGCTCAATGATTTTTTAAATTGCTGTGG) and 16S- (CCGGTCTGAACTCAGATCAAGT). The 16S-rDNA region is adequate to investigate the tick diversity because it is commonly sequenced for several species (Rodríguez-Vivas et al. 2023).

Both PCR products were sent for sequencing to Macrogen, Inc. in Seoul, South Korea. The resulting sequences measuring 350 base pairs (bp) were visualized and manually edited using the MEGA-X® software. After editing, each sequence was compared with sequences available in the NCBI database using BLASTn (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) using the NCBI core nucleotide database (core_nt) to determine identity and coverage percentages (Altschul et al. 1990). The organism or taxon of interest was not specified for the sequence search, and the Models (XM/XP) and uncultured/environmental sample sequences were not excluded. Both sequences were submitted to GenBank under Accession numbers PQ299193 and PQ299194.

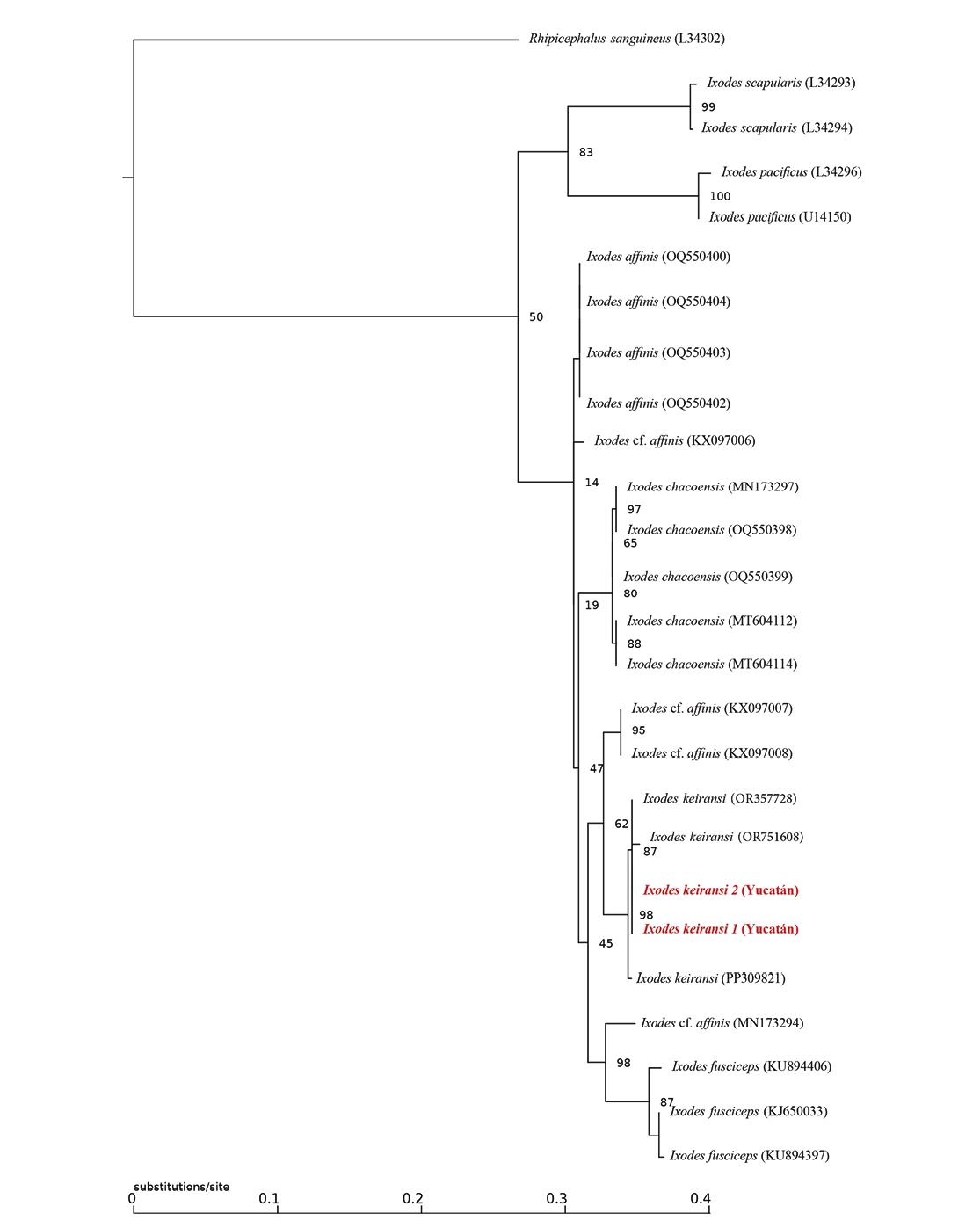

The edited sequences were globally aligned with several neotropical Ixodes sequences obtained from GenBank using the CLUSTAL-W algorithm in MEGA-X® (Kumar et al. 2018), and the phylogenetic tree was constructed in IQ-TREE (http://www.iqtree.org/) using the maximum likelihood method with 1,000 Bootstrap replicates (Tamura et al. 2004).

As illustrated in the phylogenetic tree (Figure 2) derived from the partial sequences of the 16S-rDNA gene, both specimens were identified as I. keiransi. The identity and coverage percentages yielded from BLASTn were 100% for both sequences.

The parasitism of I. keiransi (reported as I. affinis) has been described in wild rodents at several sites in Yucatán, but there are no records of I. keiransi parasitizing P. yucatanicus in the region (Palomo-Arjona et al. 2024; Núñez-Corea et al. 2024); however, the present study is the first to identify the ingestion of this tick by P. yucatanicus, underscoring the need for further research into oral route transmission of tick-borne diseases. In this study, neither the rodent nor the tick were tested for the detection of Borrelia, Rickettsia, or Bartonella.

Several families and genera of small rodents, including Peromyscus, are reservoirs of several vector-borne pathogens and are essential for generating and maintaining transmission cycles and the epidemiology of the diseases they cause (Panti-May et al. 2021). These animals are a food source for immature stages of ectoparasites (larvae and nymphs) (Palomo-Arjona et al. 2024) and contribute to maintaining the horizontal transmission of microorganisms when these immature stages without infection, especially larvae, become infected by feeding on rodents with the bacteria circulating in their bloodstream (Kiran et al. 2024; Perumalsamy et al. 2024).

Small rodents are known to incidentally ingest immature stages of ticks and other ectoparasite vectors, such as fleas (Siphonaptera), lice (Anoplura), and mites (Mesostigmata) through grooming (Panti-May et al. 2015). With this behavior, they manage to regulate the number of ectoparasites that reach the adult stage and, therefore, reduce the risk of transmission of pathogens that can affect susceptible hosts, including humans and other host animals (Krawczyk et al. 2020).

Another possible route for P. yucatanicus to ingest I. keiransi larvae is through the consumption of leaves and other vegetal or plant elements found in the soil (Zaragoza-Quintana et al. 2022). Ixodes keiransi larvae detach from their host and drop to the ground to molt for the first time, transforming into nymphs (Rodríguez-Vivas et al. 2023).

Most vector-borne pathogens are transmitted indirectly through fecal contamination or inoculation with a bite (vectorial route) during the feeding process (Meerburg et al. 2009). In the specific case of members of the genus Hepatozoon (Apicomplexa: Adeleina), infection occurs through the consumption of ticks or some of their parts (Smith 1996). This protozoan genus has previously been reported in two rodent species in the southern United States of America (Peromyscus leucopus and Sigmodon hispidus), evidencing the participation of the Peromyscus genus in the enzootic cycle of this parasite (Modarelli et al. 2020).

Zaragoza-Quintana et al. (2022) evaluated fecal samples of P. yucatanicus, where they found a higher proportion of fruit pulp, followed by chitin remains, several types of epidermis, seeds, remains of appendages of other arthropods (mites and ants) and, finally, fibers. These findings help us to suggest that the ingestion of I. keiransi by one of the specimens evaluated could have been accidental during the grooming process, as indicated by Panti-May et al. (2019) in the commensal rodents M. musculus and R. rattus captured in Yucatan.

The oral route is vital in transmitting pathogens to animals (i.e., Hepatozoon canis) (Vásquez-Aguilar et al. 2021), and this finding highlights the need for further investigation into this emerging paradigm in tick-borne disease research. In addition to the oral transmission pathway, it is crucial to consider the ecological dynamics that facilitate tick-borne diseases. For instance, the role of reservoir hosts in maintaining and amplifying pathogen populations cannot be overstated. Peromyscus yucatanicus harbors pathogens and may contribute to the interactions between ticks and their environments. Furthermore, as urbanization encroaches on wildlife habitats, increased human-wildlife interactions may lead to higher rates of ectoparasitic feeding and accidental ingestion of infected ticks, thereby exacerbating disease transmission risks. This shift underscores the necessity for interdisciplinary research that integrates ecology, veterinary science, and public health perspectives to devise effective intervention strategies against emerging zoonotic threats linked to ticks.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the administrations of Rancho Santa María (Panaba, Yucatán), Grutas Las Sartenejas (Tekax, Yucatan), and Parque Ecoturistico Kaalmankal (Tekax, Yucatan) for their facilities for bat sampling.

Literature cited

Aguilar-Tipacamú, G., et al. 2025. El impacto de la Rickettsiosis y la Borreliosis en la salud pública. Bioagrociencias 18:82-89.

Altschul, S. F., et al. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology 215:403-410.

Arroyo-Ramírez, A., et al. 2023. An unusual identification of Rickettsia parkeri in synanthropic rodents and domiciliated dogs of a rural community from Yucatán, Mexico. Zoonoses and Public Health 70:594-603.

Boulanger, N., et al. 2019. Ticks and tick-borne diseases. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses 49:87-97.

Burri, C., et al. 2012. Serological evidence of tick-borne encephalitis virus infection in rodents captured at four sites in Switzerland. Journal of Medical Entomology 49:436-439.

Clark, K. 2004. Borrelia species in host-seeking ticks and small mammals in northern Florida. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 42:5076-5086.

Dantas-Torres, F., B. B. Chomel, and D. Otranto. 2012. Ticks and tick-borne diseases: a One Health perspective. Trends in Parasitology 28:437-446.

Flores, F. S., et al. 2020. Borrelia genospecies in Ixodes sp. cf. Ixodes affinis (Acari: Ixodidae) from Argentina. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases 11:101546.

Guglielmone, A. A., S. Nava, and R. G. Robbins. 2023. Geographic distribution of the hard ticks (Acari: Ixodida: Ixodidae) of the world by countries and territories. Zootaxa 5251:1-274.

Grostieta, E., et al. 2024. First record of Coxiella sp. in Ornithodoros hasei parasitizing Rhogeessa tumida in México. Therya Notes 5:92-102.

Harrison, B. A., et al. 2010. Recent discovery of widespread Ixodes affinis (Acari: Ixodidae) distribution in North Carolina with implications for Lyme disease studies. Journal of Vector Ecology 35:174-179.

Kiran, N., et al. 2024. Effects of rodent abundance on ticks and Borrelia: results from an experimental and observational study in an island system. Parasites & Vectors 17:157.

Krawczyk, A.I., et al. 2020. Effect of rodent density on tick and tick-borne pathogen populations: consequences for infectious disease risk. Parasites & Vectors 13:34.

Kumar, S., et al. 2018. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution 35:1547-1549.

Madison-Antenucci, S., et al. 2020. Emerging tick-borne diseases. Clinical Microbiology Review 33:e00083- e00018.

Maggi, R. G., et al. 2010. Borrelia species in Ixodes affinis and Ixodes scapularis ticks collected from the coastal plain of North Carolina. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases 1:168-171.

Martínez-Ortiz, D., et al. 2019. Rickettsia spp. en garrapatas (Acari: Ixodidae) que infestan perros de una comunidad rural con antecedentes de rickettsiosis, Yucatán, México. Revista Biomédica ٣٠:٤٣-٥٠.

MacSwiney-G, Ma. C. et al. ٢٠١٢. Ecología poblacional del ratón yucateco Peromyscus yucatanicus (Rodentia: Cricetidae) en las selvas de Quintana Roo, México. Pp. ٢٣٧-٢٤٦ in Estudios sobre la biología de roedores silvestres mexicanos (F. A. Cervantes, and C. Ballesteros-Barrera, eds.). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología, Casa Abierta al Tiempo, México, DF.

Meerburg, B. G., G. R. Singleton and A. Kijlstra 2009. Rodent-borne diseases and their risks for public health. Critical Reviews in Microbiology 35:221-270.

Modarelli, J. J., et al. 2020. Prevalence of protozoan parasites in small and medium mammals in Texas, USA. International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife 11:229-234.

Nava, S., et al. 2023. Description of two new species in the Ixodes ricinus complex from the New World (Acari: Ixodidae), and redescription of Ixodes affinis Neumann, 1899. Zootaxa 5361:53-73.

Norris, D. E., et al. 1996. Population genetics of Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) based on mitochondrial 16S and 12S genes. Journal of Medical Entomology 33:78-89.

Núñez-Corea, D. A., et al. 2024. Hematophagous ectoparasites of wild and synanthropic rodents in Yucatan, Mexico. Southwest Entomologist 49:1290-1300.

Palomo-Arjona, E. E., et al. 2024. New records of rodent hosts for hard ticks in tropical forests of Yucatán, México: Implications for tick-borne diseases in human-modified landscapes. Therya Notes 5:124-132.

Panti-May, J. A., et al. 2015. Detection of Rickettsia felis in wild mammals from three municipalities in Yucatan, Mexico. Ecohealth 12:523-527.

Panti-May, J. A., et al. 2019. Diet of two invasive rodent species in two Mayan communities in Mexico. Mammalia 83:567-573.

Panti-May, J. A., M. A. Torres-Castro and S. F. Hernández-Betancourt. 2021. Parásitos zoonóticos y micromamíferos en la península de Yucatán, México: Contribuciones del CCBA-UADY. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems 24:18.

Perumalsamy, N., et al. 2024. Hard ticks as vectors: The emerging threat of tick-borne diseases in India. Pathogens 13:556.

Rodríguez-Vivas, R. I., et al. 2023. Population genetics of the Ixodes affinis (Ixodida: Ixodidae) complex in America: new findings and a host-parasite review. Parasitology Research 123:78.

Rodríguez-Vivas, R. I., et al. 2024. Monthly fluctuation of parasitism by adult Ixodes keiransi ticks in dogs from Yucatán, Mexico. Veterinary Parasitology Regional Study and Reports 53:101077.

Smith, T. G. 1996. The genus Hepatozoon (Apicomplexa: Adeleina). Journal of Parasitology 82:565-585.

Tamura, K., M. Nei and S. Kumar. 2004. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101:11030-1105.

Torres-Castro, M., et al. 2018. Rickettsia typhi in rodents from a community with history of murine typhus from Yucatan, Mexico. Revista MVZ Córdoba 23:6974-6980.

Vásquez-Aguilar, A. A., et al. 2021. Phylogeography and population differentiation in Hepatozoon canis (Apicomplexa: Hepatozoidae) reveal expansion and gene flow in world populations. Parasites & Vectors 14:467.

Yeh-Gorocica, A., et al. 2024. Prevalence of Flavivirus and Alphavirus in bats captured in the state of Yucatan, southeastern Mexico. One Health 19:100876.

Zaragoza-Quintana, E. P., et al. 2022. Abundance, microhabitat and feeding of Peromyscus yucatanicus and Peromyscus mexicanus in the Mexican tropics. Therya 13:129-142.

Associated editor: Agustín Jiménez Ruiz

Subnitted: March 12, 2025; Reviewed: August 13, 2025

Accepted: September 24 2025, Published on line: November 22, 2025.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic tree constructed from a partial fragment (340-350 pb) of the 16SrDNA gene using the maximum likelihood method and the K3Pu+F+R2 nucleotide substitution model. Bootstrap values greater than 0.4 are indicated at the nodes of the tree. The scale bar represents nucleotide substitutions per site. It includes the sequences recovered in this study in red (accessions PQ299193.1 and PQ299194.1).