THERYA NOTES 2025, Vol. 6: 87-93

Beneath umbrellas: Noteworthy records of tent-roosting

bats in Guatemala’s Maya Biosphere Reserve

Bajo sombrillas: registros notables de murciélagos

tienderos en la Reserva de la Biosfera Maya, Guatemala

Ana Lucía Arévalo1*, Luis A. Trujillo2,3, Ricardo Sánchez-Calderón1,4, Rodrigo A. Medellín5, and Bernal Rodríguez-Herrera6,7

1Sistema de Estudios de Posgrado, Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica (UCR), San Pedro de Montes de Oca, 11501-2060, San José, Costa Rica. Email: arevalofigueroaanalucia@gmail.com (ALAF); ricardosanchezc92@gmail.com (RSC).

2Fundación Defensores de la Naturaleza, Guatemala City, Guatemala.

3Escuela de Biología, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Guatemala City, Guatemala. Email: trujillososaluis@gmail.com.

4 The School for Field Studies, Center for Amazon Studies (SFS), San Martín, Tarapoto 22201, Peru.

5Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México, México. Email: medellin@iecologia.unam.mx.(RML)

6Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica.

7Centro de Investigación en Biodiversidad y Ecología Tropical, Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica. Email: bernal.rodriguez@ucr.ac.cr (BRH)

*Corresponding author

Neotropical tent-roosting bats can modify approximately 77 species of plants as tents, most inhabiting lowland tropical forests. At least ten of the 22 known species of tent-roosting bats occur in Guatemala. Many studies have investigated their roosting ecology in Central America. Nevertheless, this behavior is still undocumented in this country. Here, we describe for the first time the use of Sabal mauritiiformis and Cryosophila stauracantha palm trees with tents occupied by Artibeus jamaicensis and Dermanura sp. in two localities of the Maya Biosphere Reserve, (MBR) Guatemala. We report a total density of 35.11 (tents/ km2) for both localities, most of them with big seeds underneath. All S. mauritiiformis tents presented a type of ceiling modification that had never been reported before. This study furthers our understanding of bat ecology and behavior in Central America. We expect many tent architectures to be present in the region and tents in plant species not reported before since Guatemala has a great diversity of plants that, according to the literature, are used as tents by bats in other tropical regions. We also expect that these bats will play an important role as seed dispersers in the Guatemalan forests.

Key words: Sabal mauritiiformis; Neotropical bats; Guatemala; tents.

Los murciélagos neotropicales que habitan en tiendas modifican aproximadamente 77 especies de plantas como refugios, la mayoría de las cuales se distribuyen en bosques tropicales de tierras bajas. Al menos diez de las 22 especies de murciélagos que ocupan estas tiendas habitan en Guatemala. Varios estudios han investigado la ecología del refugio de estas especies en Centroamérica. Sin embargo, este comportamiento aún no ha sido documentado en este país. Describimos por primera vez el uso de Sabal mauritiiformis y Cryosophila stauracantha como refugios por Artibeus jamaicensis y Dermanura sp. en dos localidades de la Reserva de la Biosfera Maya (RBM), Guatemala. Reportamos una densidad total de 35.11 (tiendas/km2) para ambas localidades, la mayoría de estas con semillas debajo. Todas las tiendas de S. mauritiiformis presentaban una modificación tipo “techo” nunca antes reportada.. Este estudio abre la puerta para seguir avanzando en la comprensión de la ecología y el comportamiento de los murciélagos en Centroamérica. Esperamos que una alta diversidad de arquitecturas y de especies de plantas aún no reportadas anteriormente estén presentes en esta región, ya que Guatemala cuenta con una gran diversidad de plantas que, según la literatura, son utilizadas como tiendas por murciélagos en otras regiones neotropicales. Asimismo, esperamos que estos murciélagos cumplan un papel importante como dispersores de semillas en los bosques de Guatemala.

Palabras clave: Sabal mauritiiformis; Murciélagos neotropicales; Guatemala; tiendas de campaña.

© 2025 Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología, www.mastozoologiamexicana.org

Guatemala is home to 105 species of bats grouped in 8 families: Phyllostomidae, Vespertilionidae, Molossidae, Emballonuridae, Mormoopidae, Noctilionidae, Natalidae, and Thyropteridae (Kraker-Castañeda et al. 2016; Trujillo et al. 2022; Trujillo et al. 2024). The country’s great diversity of bat species and other taxonomic groups is explained by its location between North and South America and its extensive variations in altitude and precipitation, making it one of Latin America’s repositories of biodiversity (Birner et al. 2005). Despite the richness of bat species, this group is still not well-studied as most studies have focused on their community composition level (Meachem 1968; Dickerman et al. 1981; Schulze et al. 2000), cave-dwelling species (Kraker-Castañeda et al. 2023; Kraker-Castañeda et al. 2024), infectious diseases (Ubico and McLean, 1995; Bai et al. 2011; Morán et al. 2015), and taxonomic lists (Pérez et al. 2012; Kraker-Castañeda et al. 2016).

Of the 51 species of Phyllostomidae documented in Guatemala, only ten have been confirmed to exhibit tent-roosting behavior. This group includes members of the genera Dermanura, Artibeus, Uroderma, and Vampyressa (Rodríguez-Herrera et al. 2007). Many studies have researched the roosting ecology of tent-roosting bats in Costa Rica (Brooke, 1897; Chaverri and Kunz, 2010; Gutiérrez-Sanabria, 2010; Rodríguez-Herrera et al. 2018; Rodríguez et al. 2021) and Panama (Choe, 1997; Lim, 1998; Cvecko, 2022); however, information on this behavior is absent in Guatemala.

In the Neotropics, around 22 species of Phyllostomidae are known to show this behavior, occurring with the greatest species diversity in Brazil, Colombia, and Perú (Tello and Velazco, 2003). These bats modify approximately 77 species of plants as tents, most inhabiting lowland tropical forests, being Arecaceae, Heliconiaceae, and Araceae, the most representative plant families, all of them present in Guatemala. Eight types of tent architecture are known to date: apical, bifid, umbrella, boat, conical, pinnate, boat-apical, and paradox (Rodríguez-Herrera et al. 2007). Since many of the tent-roosting bat species and their associated roosting plant species have been reported for Guatemala, we expect this behavior to be present in this country. Here, we report the tent-roosting behavior in two localities at the Maya Biosphere Reserve (MBR), Petén, Guatemala, for the first time. This report is not only the first for the study area but also for the country. It contributes to bringing attention to an understudied but important biological interaction, especially in the Central American region, and highlights the need to continue reporting these sightings.

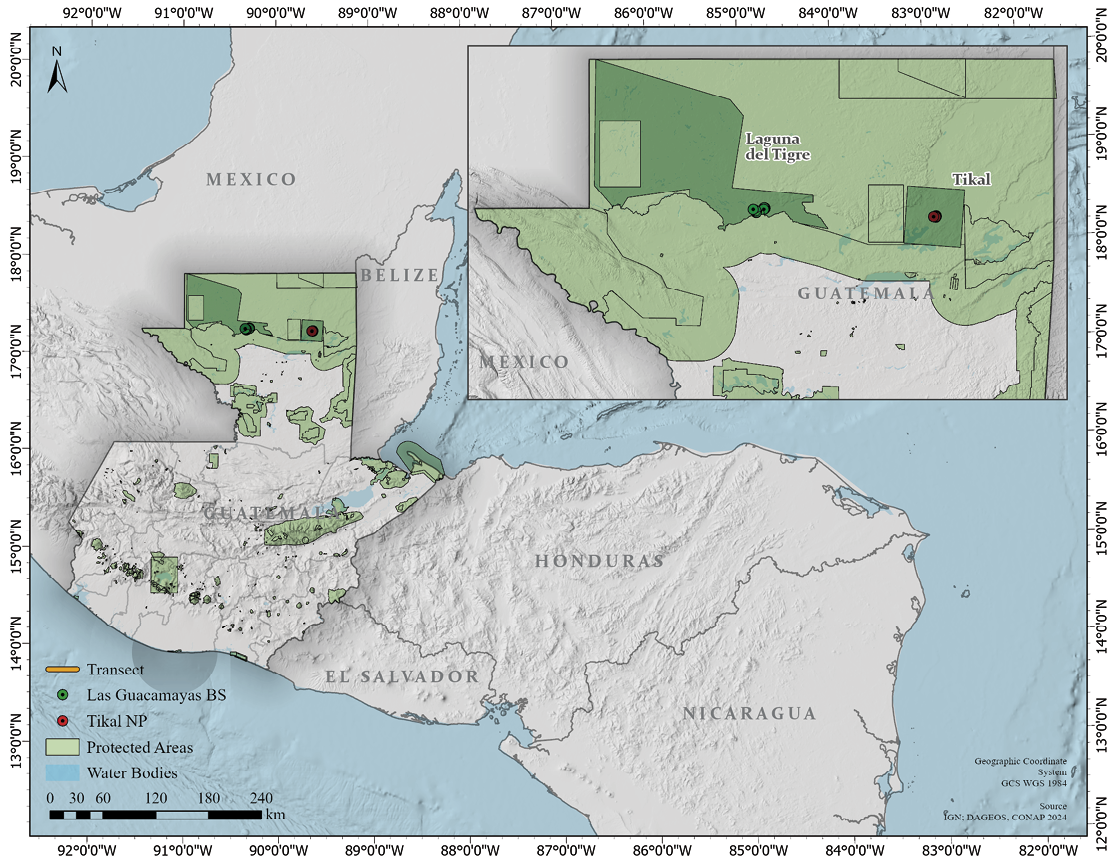

Located in northern Guatemala, the Maya Biosphere Reserve (MBR), department of Petén, comprises Central America’s largest tropical lowland forest, with a wide range of undisturbed natural habitats (Alarcón-Méndez et al. 2023). This region presents a medium temperature of 22 – 29° C and 1,000 mm – 1,900 mm annual precipitation (CONAP, 2016). We conducted this study in January 2024 on a short visit to Tikal National Park (17.2166, -89.6166 O) and Estación Biológica “Las Guacamayas (EBG)”, Parque Nacional Laguna del Tigre (17.247216, -90.29288), both protected areas are part of the MBR (Figure 1). Tikal National Park (TNP) protects one of the largest ancient cities of the Maya Civilization, where it predominates highland forests composed of species such as Cedrella odorata and Brosimum alicastrum, among others (CONAP, 2004). At the Estación Biológica “Las Guacamayas,” the dominant habitat is tropical dry forest (Murphy and Lugo 1986), mainly composed of savannas, wetlands, and highland forests (Colombo et al. 2015). Our study design was as simple as doing trails at least 0.5 km distance surveying for bat tents 0.02 km from the trail (wide). We surveyed a total area of 0.01046 km2 and walked 5.23 km for both study sites, divided into shorter routes. In Estación Biológica “Las Guacamayas,” we did two trails totaling 3.43 km (1.06 km and 2.37 km each x 0.02 km wide), and in Tikal National Park, we did two trails totaling 1.80 km (1.09 km and 0.71 km each x 0.02 km wide). For each route, we took the following data whenever we spotted a bat tent: 1) geographic coordinates, 2) plant species, 3) tent architecture, 4) cut shape, 5) bat species (if the tent was occupied), and 6) if there were seeds under the tent.

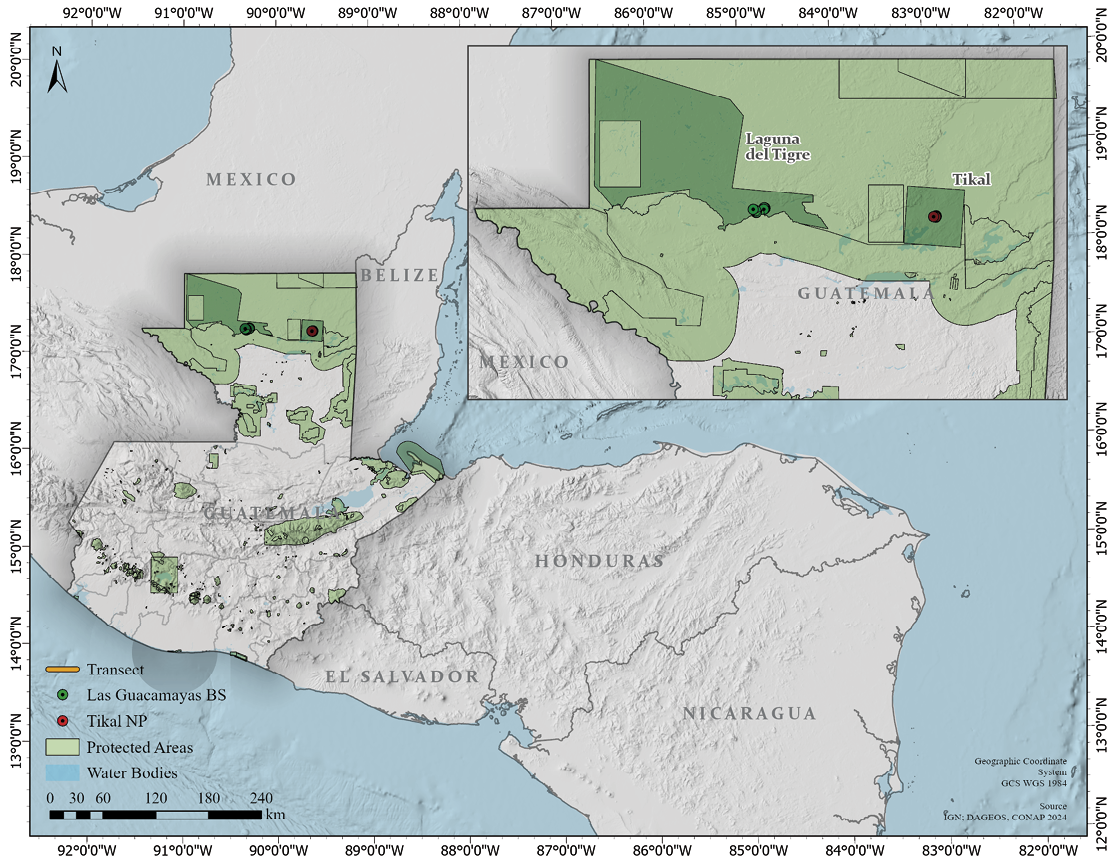

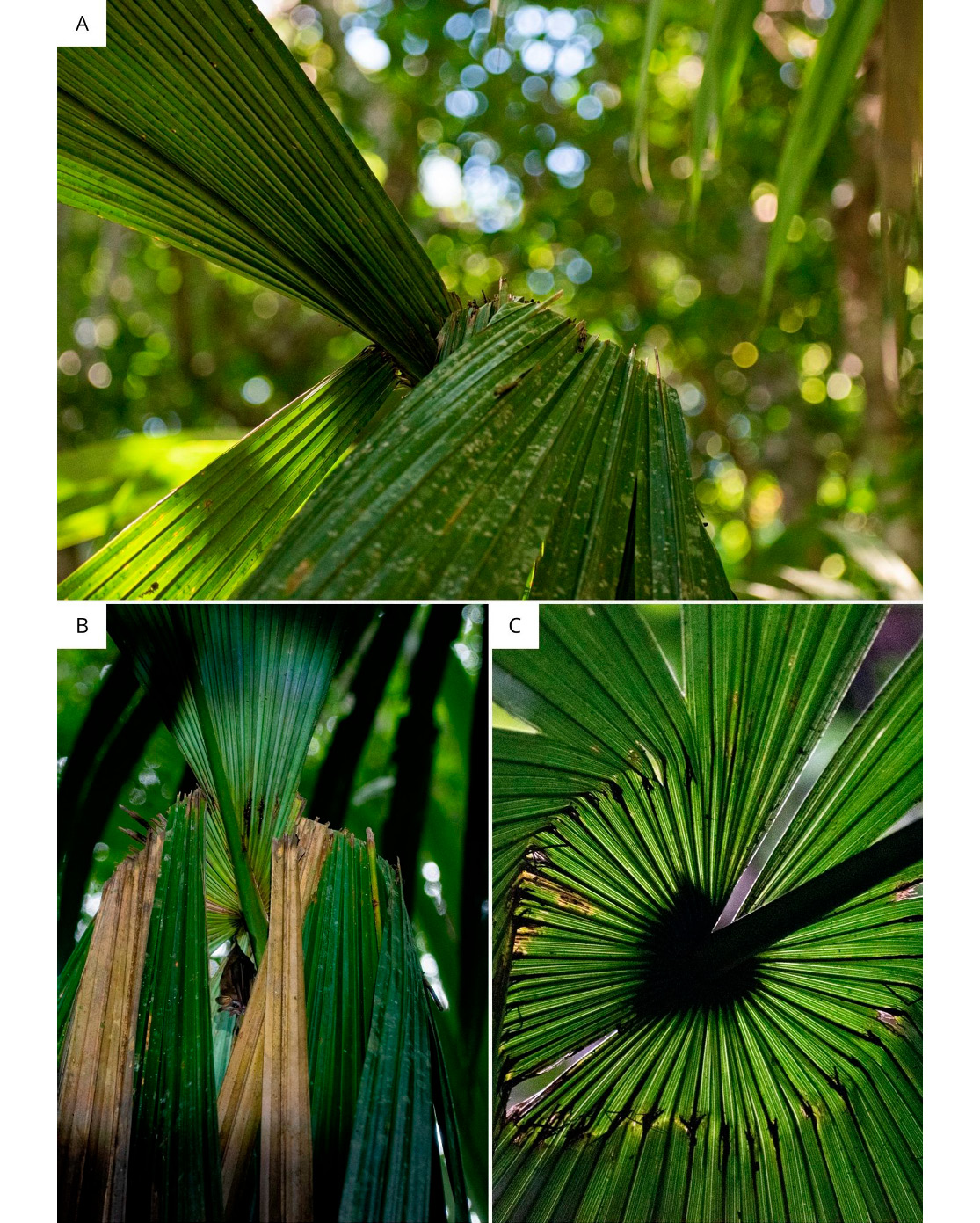

We found 38 tents in Estación Biológica “Las Guacamayas” and 47 tents in Tikal National Park. We report a total density of 9.88 (tents/km2) for EBG and 25.23 (tents/km2) for TNP (Table 1). 66 of 85 tents had seeds underneath (Table 2). In both study localities, we found that Sabal mauritiiformis and Cryosophila stauracantha (Arecaceae) were used as tents in umbrella architecture and presented a heart-shaped cut. We only recorded 3 tents occupied, 2 by Dermanura sp. (C. stauracantha and S. mauritiiformis) and 1 Artibeus jamaicensis (S. mauritiiformis) (Table 2). All C. stauracantha tents presented a type of ceiling modification (Figure 2) that had never been reported before (Figure 2).

Our study is the first to report bats that use tents in the Northern Central American region, even though 10 tent-roosting bat species are reported for Guatemala. Guatemala’s MBR does not count with an updated bat species list. Still, according to the species distribution and habitat requirements, only 6 tent-roosting species occur in the MBR: Uroderma convexum, Artibeus jamaicensis, A. lituratus, Dermanura phaeotis, D. watsoni, and Vampyressa thyone (Lou and Yurrita, 2005). These species can use up to 56 plant species and design 8 tent architectures throughout their distribution (Rodríguez-Herrera et al. 2007). Here, we only reported two bat species using tents (Dermanura sp. and Artibeus jamaicensis), two plant species (Sabal mauritiiformis and Cryosophila stauracantha), and one type of architecture (umbrella), highlighting the urgent need to report this type of sightings to learn more about these species in other Central American localities.

Plant and tent architecture can change within localities, season and habitat types. Tent construction patterns (plant species and architectures) documented in this study area are quite different than those recorded in other studies. Villalobos-Chaves et al. (2016) reported 225 bat tents corresponding to 4 architectures and 14 plant species in 0.55 km2 of Costa Rica’s rainforest (409 tents/km2 density). The number of tents available in each area and the plants used by bats to build their roosts could change in response to several factors, such as the availability of plant resources across space, time, and bat species preferences and behavioral plasticity (Choe and Timm, 1985; Chaverri and Kunz, 2006; Rodríguez-Herrera et al. 2007). The factors mentioned above could explain why we found a much smaller number of tents in the MBR, adding that this region is not as rainy as the region studied by Villalobos-Chaves et al. (2016).

All the tents we found were umbrella-type. Most tents with this type of architecture are built on species of the Arecaceae family (Herrera-Victoria et al. 2018), such as the two species reported here. (S. mauritiiformis and C. stauracantha). However, this architectural style is not present in all palms. The umbrella tent is the third most used by bat species in the Neotropics since four bat species construct them in around eight different plant species throughout the region (Rodríguez-Herrera et al. 2007). S. mauritiiformis tents presented a type of ceiling modification (Figure 2) that had never been reported before. Palms are distinguished by their costapalmate leaves, which are difficult to cut, to which we attribute the modification by bats. We observed a great abundance of S. mauritiiformis, especially at Estación Biológica “Las Guacamayas”; this might be due to using their leaves as roofs for traditional Maya houses since prehispanic times (Martínez-Ballesté et al. 2008). However, the preference for bat use for this plant species in our study localities is unclear.

About 77.6% of the bat tents, we found had large seeds underneath. Melo et al. (2009) state that Neotropical tent-roosting bat species can disperse around 43 species of large seeds, playing a key role in tropical forest regeneration. However, further research should focus on identifying which species of large seeds bats disperse in Guatemalan forests.

This study is the first report of tent-roosting behavior in Guatemala, highlighting the use of two Arecaceae species and a variant of the umbrella tent architecture for the first time. These results highlight the importance of studying tent roosting behavior in data-deficient areas, and It’s the first step in continuing to look for this behavior in the species mentioned above. Further research in Guatemala should focus on tent-roosting behavior. As the literature indicates for other Neotropical areas such as Costa Rica and South America, we expect many architectures in the region and tents in plant species not reported before (Rodríguez-Herrera, 2009). Furthermore, tent-making bats are important seed dispersers in rainforests (Melo et al. 2009), and further research will document the scale and scope of this ecosystem service for Guatemalan forests.

Acknowledgments

The National Geographic Society financially supported this expedition as part of the project NGS-102401R-23: “Exploring bat architecture: Their homes, neighborhoods, and environmental services they provide us,” granted to B. Rodríguez Herrera. We thank J. Tut, E. García, G. Aldana, and Estación Biológica “Las Guacamayas” staff for assisting us with fieldwork. To the students who attended the course “Roosts, ecology, and Conservation of Neotropical Bats” for participating in the fieldwork. Finally, we thank two anonymous reviewers whose comments improved our manuscript. The National Council of Protected Areas (CONAP, Guatemala) issued the Research License for this research.

Literature cited

Alarcón-Méndez, M., Duminil, J. 2023. Implications of community forest management for the conservation of the genetic diversity of big-leaf mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla King, Meliaceae) in the Maya Biosphere Reserve, Petén, Guatemala. Trees, Forests and People 11.

Bai, Y., Rupprecht, C. 2011. Bartonella spp. in bats, Guatemala. Emerging infectious diseases 17:1269-1272.

Birner, R., H. Wittmer, A. Berchöfer, Y M. Mühlenberg. 2005. Prospects and challenges for biodiversity conservation in Guatemala. Pp. 285–286 en Valuation and Conservation of Biodiversity: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on the Convention on Biological Diversity (Markussen, M., R. Buse, H. Garrelts, M. A. Máñez Costa, S. Menzel, y R. Marggraf, eds.). Springer. Berlín, Alemania

Brooke, A. P. 1987. Tent construction and social organization in Vampyressa nymphaea (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) in Costa Rica Journal of Tropical Ecology. 3:171–175.

Colombo, R., Gager, Y. 2017. Rapid assessment of bat diversity in the biological station ‘Las Guacamayas’ (‘Laguna del Tigre’ National Park, Guatemala). Barbastella 10:1-17.

Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas (CONAP). 2004. Plan Maestro Parque Nacional Tikal 2004-2008. Guatemala, Guatemala.

Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas (CONAP). 2016. Reserva de la Biósfera Maya Plan Maestro, segunda actualización tomo I. Guatemala, Guatemala.

Chaverri, G., Kunz, T. H. 2006. Roosting Ecology of the Tent‐Roosting Bat Artibeus watsoni (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) in Southwestern Costa Rica 1. Biotropica: The Journal of Biology and Conservation 38:77-84.

Chaverri, G., T. H. Kunz. 2010. Ecological determinants of social systems: perspectives on the functional role of roosting ecology in the social behavior of tent roosting bats. Pp. 275–318 in Advances in the study of behavior, vol. 42 (R. Macedo, ed.). Academic Press, Burlington.

Choe, J. C. A. 1997. New Tent Roost of Thomas’ Fruit-eating Bat, Artibeus watsoni (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae), in Panama. Korean Journal of Biological Sciences 1: 313-316.

Cvecko, P., M. Tschapka. 2022. New architecture of leaf-tents in American oil palms (Elaeis oleifera) used by Pacific tent-making bat (Uroderma convexum) in Panama. Mammalia 86: 355-358.

Dickerman, R.W., Seymour, C. 1981. Notes on bats from the Pacific Lowlands of Guatemala. Journal of Mammalogy 62:406-411.

Gutiérrez-Sanabria, D. R. 2015. Leaf-roost selection of Carludovica palmata by tent-roosting bat Dermanura watsoni in Piro Biological Station, Península de Osa, Costa Rica. Revista Biodiversidad Neotropical 5: 23–28.

Herrera-Victoria, A. M., Kattan, G. H. 2018. The dynamics of tent‐roosts in the palm Sabal mauritiiformis and their use by bats in a montane dry forest. Biotropica 50:282-289.

Kraker-Castañeda, C., Echeverría-Tello, J.L. 2016. Lista actualizada de los murciélagos (Mammalia, Chiroptera) de Guatemala. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 87:409-416.

Kraker-Castañeda, C., Pérez-Consuegra, S.G. ٢٠٢٣. Ampliación del límite noroeste de distribución de Phyllostomus hastatus y descripción de sus pulsos de ecolocalización. Therya Notes ٤:٦٠-٦٧.

Kraker-Castañeda, C., Pérez-Consuegra, S.G. ٢٠٢٤. Implementación de métodos complementarios para muestreo de murciélagos en un paisaje kárstico del centro-norte de Guatemala, Centroamérica. Arxius Miscellanea Zoologica 22:95-113.

Lim, B.K. 1998. Relative abundance of small tent-roosting bats (Artibeus phaeotis and Uroderma bilobatum) and foliage tents (Carludovica palmata) in Panama. Bat Research News 39: 1-3.

Lou, S., Yurrita, C. 2005. Análisis de nicho alimentario en la comunidad de murciélagos frugívoros de Yaxhá, Petén, Guatemala. Acta Zoológica Mexicana 21:83–94.

Martínez-Ballesté, A. Caballero, J. 2008. The effect of Maya traditional harvesting on the leaf production, and demographic parameters of Sabal palm in the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico. Forest Ecology and Management 256:1320-1324.

Meachem, A. 1968. Notes on bats from Tikal, Guatemala. Journal of Mammalogy 49: 516-520.

Melo, F., Ceballos, G.G. 2009. Small Tent-Roosting Bats Promote Dispersal of Large-Seeded Plants in a Neotropical Forest. Biotropica 41:737-743.

Morán, D., Recuenco, S. 2015. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding rabies and exposure to bats in two rural communities in Guatemala. BMC research notes 8:1-7.

Murphy, P.G., Lugo, A. E. 1986. Ecology of Tropical Dry Forest. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 17:67-88.

Trujillo, A., Mártinez-Fonseca, J., G. 2024. Noteworthy records of Myotis Kaup, 1829 species in northeastern Guatemala, including the first record of M. volans (H. Allen, 1866) (Chiroptera, Vespertilionidae) from the country. Checklist 20:969-975.

Trujillo, A., Pérez, S.G. 2021. Noteworthy records of bats of the genus Eumops Miller, 1906 from Guatemala: first confirmed record of Underwood’s Bonneted Bat, Eumops underwoodi Goodwin, 1940 (Mammalia, Chiroptera, Molossidae), in the country. Checklist 17:1147-1154.

Rodríguez-Herrera, B., R., R. M. Timm. 2007. Neotropical tent-roosting bats, primera edición. INBio, San José, Costa Rica.

Rodríguez-Herrera, B., Otárola, M. F. 2018. Ecological networks between tent-roosting bats (Phyllostomidae: Stenodermatinae) and the plants used in a Neotropical rainforest. Acta Chiropterologica 20:139-145.

Rodríguez, M. E., Rodríguez-Herrera, B. 2021. Preference and design variability on umbrella tents built by Artibeus watsoni on two sympatric Carludovica species (Cyclanthaceae) in Costa Rica. Acta Chiropterologica 23:215-223.

Schulze, M.D., Whitacre, D.F. 2000. A Comparison of the Phyllostomid Bat Assemblages in Undisturbed Neotropical Forest and in Forest Fragments of a Slash-and-Burn Farming Mosaic in Peten, Guatemala. Biotropica 32:174-184.

Rick, A. M. 1968. Notes on bats from Tikal, Guatemala. Journal of Mammalogy 49:516-520.

Tello, J.G., Velazco, P. 2003. First description of a tent used by Platyrrhinus helleri (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae). Acta Chiropterologica 5:269-276.

Pérez, S., McCarthy, T. 2012. Five new records of bats for Guatemala, with comments on the checklist of the country. Chiroptera. Neotropical 8:1106-1110.

Ubico, S. R., Mclean, R. G. 1995. Serologic survey of neotropical bats in Guatemala for virus antibodies. Journal of wildlife diseases 31:1-9.

Villalobos-Chaves, D., Rodríguez-Herrera, B. 2016. Understory bat roosts, availability and occupation patterns in a Neotropical rainforest of Costa Rica. Revista de Biología Tropical. 64: 1333-1343.

Associate editor: Romeo A. Saldaña Vázquez.

Submitted: November 18, 2024; Reviewed: March 13, 2025.

Accepted: May 29, 2025; Published on line: August 6, 2025.

DOI: 10.12933/therya_notes-24-204

ISSN 2954-3614

Figure 1. Study sites are represented by green polygons and sampling points by red and green circles. The Guatemalan System of Protected Areas is integrated into the main map (green polygons) (https://conap.gob.gt/direccion-de-analisis-geoespacial/) is integrated into the main map. Map elaborated by L. Trujillo.

Table 1. Number of tents registered in both study sites.

|

Locality |

Trail (km2) |

No. tents |

Density (tents/km2) |

|

EBG |

0.00212 |

8 |

3.77 |

|

EBG |

0.00474 |

29 |

6.11 |

|

9.88 |

|||

|

TNP |

0.00218 |

32 |

14.67 |

|

TNP |

0.00142 |

15 |

10.56 |

|

25.23 |

EBG: Estación Biológica “Las Guacamayas”, TNP: Tikal National Park.

Table 2. Plant species used as tents in both study sites.

|

Locality |

Plant species |

No. Tents |

Architecture |

Tents with seeds |

|

EBG |

Sabal mauritiiformis |

12 |

Umbrella |

6 |

|

Cryosophila stauracantha |

26 |

Umbrella |

22 |

|

|

TNP |

Sabal mauriitiformis |

42 |

Umbrella |

36 |

|

Cryosophila stauracantha |

5 |

Umbrella |

2 |

|

|

Total |

85 |

66 |

EBG: Estación Biológica “Las Guacamayas”, TNP: Tikal National Park. Tents with seeds = seeds transported and consumed by bats in their roosts.

Figure 2. A) and B) Sabal mauritiiformis modified as tent. C) Umbrella tent of C. stauracantha heart-shaped cut. Photos by L. Trujillo.

Figure 3. Occupied tents registered. A) Artibeus jamaicensis roosting in an umbrella S. mauritiiformis tent. B) Dermanura sp. roosting in an umbrella C. stauracantha tent. Photos by L. Trujillo.