Mustelids comprise a diverse group of small- to medium-sized carnivores comprising 2 subfamilies, 22 genera, and 59 species (Wilson and Reeder 2005). They are widely distributed in all continents, except Antarctica and Australia, in various terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, and even in anthropic or urban areas (Grifiths 2000; Nowak 2005; Wilson and Mittermeier 2009). They exhibit a wide range of dietary habits, ranging from omnivores to strict carnivores (Nowak 2005). The role of these carnivores in ecosystems has also been noted, where they are seed dispersers in some cases (López-Bao et al. 2011; González-Varo et al. 2015). Mexico is home to 6 species, of which Mustela frenata has a wide distribution; others, like Eira barbara, Galictis vittata, Enhydra lutris, and the otters Lontra annectens and L. canadensis, have a more restricted distribution (Ceballos and Oliva 2005). The sea otter (Enhydra lutris), which inhabits the coasts of Baja California, is virtually extinct (Gallo-Reynoso 2013).

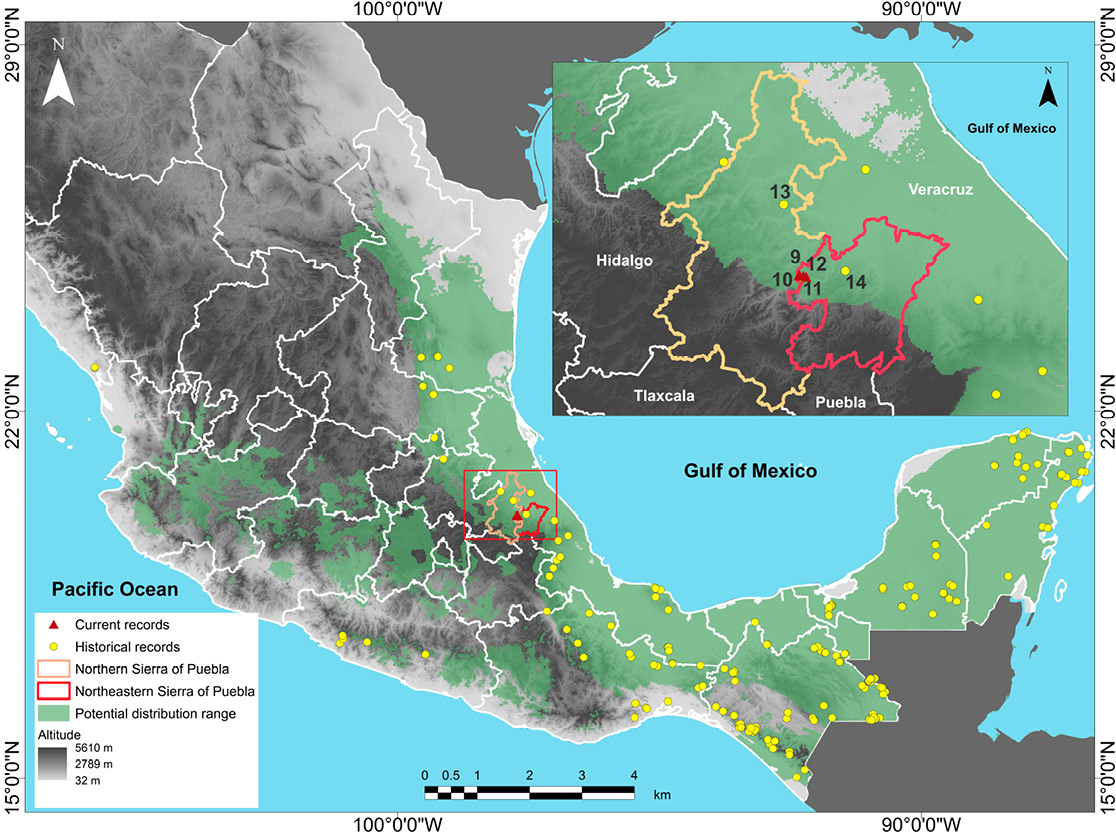

Eira barbara (Tayra) is a Neotropical mustelid distributed from the coasts of central Mexico to northern Argentina (Presley 2000; Larivière and Jennings 2009). It is considered an opportunistic omnivore, observed to consume a wide variety of fruits, small vertebrates, and invertebrates (Álvarez del Toro 1991; Presley 2000; Soley and Alvarado-Díaz 2011). It shows semi-arboreal habits, using both terrestrial and arboreal substrates for displacement (Álvarez del Toro 1991). This species is active day and night, with peak activity periods during the early morning and evening hours (Villafañe-Trujillo et al. 2021). In Mexico, there are records of E. barbara in the states of Yucatán (Hernández-Hernández et al. 2019), Quintana Roo (Chávez 2005), Chiapas (Espinosa-Medinilla et al. 2018), Guerrero (Ruiz-Gutiérrez et al. 2017), Oaxaca (Espinosa-Lucas et al. 2015), Veracruz (Ríos-Solís et al. 2021), Hidalgo (García et al. 2016), Puebla (Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2005), Querétaro (López-González and Aceves 2007), Tamaulipas (Chávez 2005), and Sinaloa (Ruiz-Gutiérrez et al. 2017; Figure 1). It is one of the carnivore mammals with a wide distribution in tropical forests; however, these ecosystems are undergoing the greatest loss of vegetation cover related to changes in land use (Mendoza et al. 2023).

Galictis vittata (Grison) is a solitary species, mainly diurnal, although it can be active at night (Sunquist et al. 1989; Yensen and Tarifa 2003). It has a carnivorous diet, including rodents, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish (Bisbal 1986; Sunquist et al. 1989; Roemer et al. 2009; Hidalgo-Mihart et al. 2018). It thrives in the proximity of water bodies, such as rivers and streams, where it usually swims; although it can climb, it usually forages on the ground (Álvarez del Toro 1991). The Grison is distributed from central-eastern and southeastern Mexico down through Central America to southern Brazil, Bolivia, and northern Argentina (Yensen and Tarifa 2003; Bornholdt et al. 2013; Jiménez-Alvarado et al. 2016). G. vittata is considered a species with low-density and stable populations (Arita et al. 1990; Cuarón et al. 2016), and its conservation status is uncertain (De la Torre et al. 2009; Hernández-Sánchez et al. 2017).

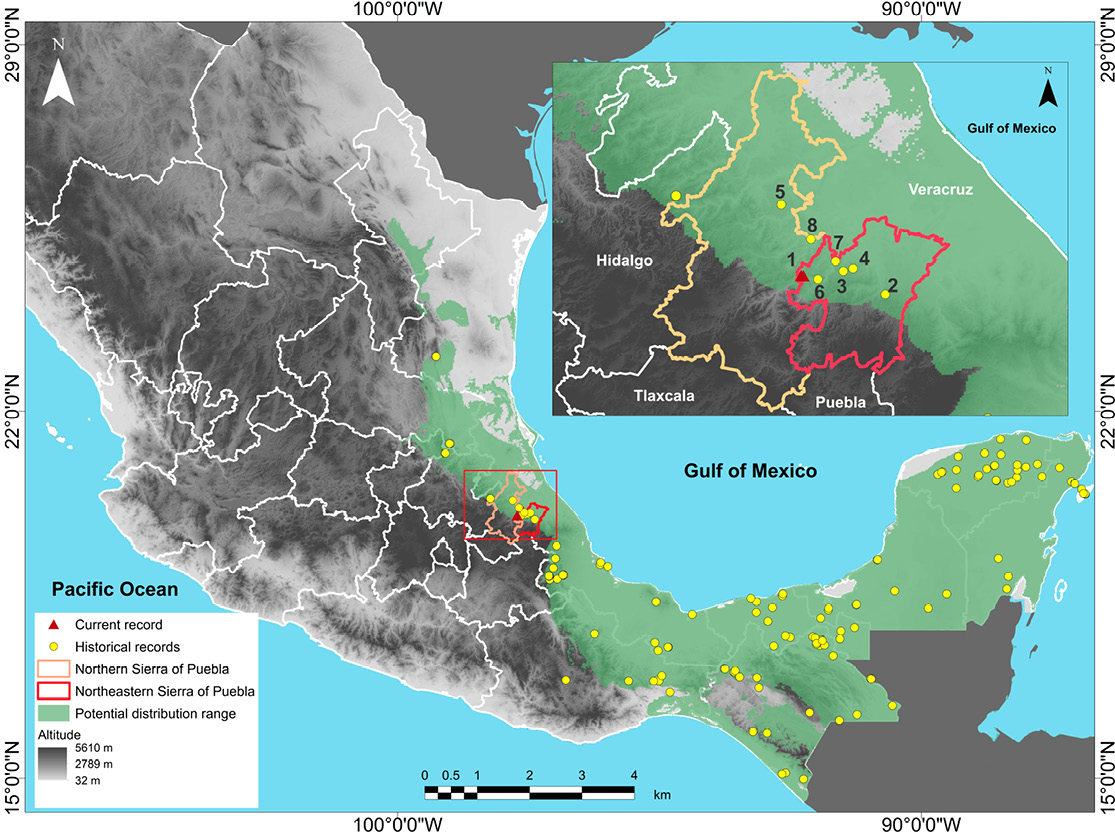

In Mexico, G. vittata has been recorded on the eastern slopes of the states of Tamaulipas (Contreras-Días et al. 2020), Hidalgo (Mejenes-López et al. 2010), Veracruz (Gallina and González-Romero 2018), Puebla (Lucas-Juárez et al. 2021; Hernández-Hernández et al. 2022); southward to Oaxaca (Espinosa-Lucas et al. 2015), Chiapas (De la Torre et al. 2009), Tabasco (García-Morales and Diez de Bonilla-Cervantes 2021), Campeche (Contreras-Moreno et al. 2023), Yucatán (Sosa-Escalante et al. 2013), and Quintana Roo (Chávez-León 1987; Figure 2). This species has been recorded mainly in tropical evergreen, sub-evergreen, and sub-deciduous forests, and occasionally in mountain cloud forests (Gallina et al. 1996; De la Torre et al. 2009; Pérez-Solano et al. 2018). It has also been recorded in localities with secondary or modified vegetation (Hernández-Hernández et al. 2022; Sánchez-Brenes and Monge 2022), and even in urban and suburban areas (Contreras-Díaz et al. 2020; García-Morales and Diez de Bonilla-Cervantes 2021).

The Northeastern Sierra of Puebla is located in the transition zone of two physiographic units, the Sierra Madre Oriental and the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt. This region is covered by mountain cloud forests and tropical forests that contribute to its being considered one of the most important areas Puebla in terms of its mammal composition (CONABIO 2011). This area has recorded 17 species of carnivorous mammals (Ramírez-Bravo and Hernández-Santin 2016), considered key drivers of ecosystem dynamics (Servín 2013). Two of these species are worth mentioning: G. vittata, a species listed as threatened in the Mexican legislation, and E. barbara, listed as Endangered of Extinction (SEMARNAT 2010), due to destruction and fragmentation of their habitat as a result of conversion to agricultural land, livestock raising, and urban development (Oliveira 2009).

Galictis vittata and E. barbara are among the least studied carnivorous mammals in Mexico. There is insufficient information available on the ecology, distribution, and conservation status of both species in the country and at a global level (López-González and Aceves-Lara 2007; Hidalgo-Mihart et al. 2018; González-Maya et al. 2019). Since the presence of E. barbara and G. vittata was first documented in Puebla in Coxcatlán de Osorio and Zihuateutla, respectively (Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2005), records for this state have been scarce. For all the above, the objective of this study was to contribute to the knowledge about the presence of G. vittata and E. barbara in the Northeastern Sierra of Puebla, Mexico.

This study was carried out in the municipality of Zapotitlán de Méndez, in the Northeastern Sierra of Puebla (19º58’10” to 20º01’36” N; 97º38’36” to 97º44’24” W). The climate is temperate humid, with a mean annual temperature of 22 °C and a mean annual precipitation of 2750 mm (INEGI 2005). The local landscape comprises cloud forests at high altitudes and ravines; fragments of medium sub-evergreen forest and pine-oak forest are also present. These vegetation types are within a matrix of anthropic uses that include mainly coffee plantations and induced pastures (Evangelista-Oliva et al. 2010).

Systematic sampling with camera traps was carried out from March to May 2023. In each of 10 stations, a Stealth Cam camera trap (model STC-BT16) was randomly installed at 30 cm to 40 cm above the ground in sites where traces (footprints, excreta, trails) of wild mammals were found. The distance between stations was 1 km to avoid leaving large gaps unsampled. Camera traps remained in operation 24 hours a day and were set to capture one photograph and one 30-second video per event, recording the date and time of each event. A record from a trap station was considered independent when the time between two consecutive photograph records exceeded 60 minutes (Tobler et al. 2008; Srbek-Araujo and García Chiarello 2005). Camera traps were installed in shaded coffee plantations with remnants of mountain cloud forest.

A map was made that illustrates the potential distribution of E. barbara and G. vittata (Lavariega and Briones-Salas 2019a, b), the records of the National Biodiversity Information System (CONABIO 2020), the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF 2024), and the Neotropical Carnivores database (Nagy-Reis et al. 2020), as well as records published in the state of Puebla, to overlap them with the photographic records obtained in this study.

Two independent photographic records of E. barbara were captured with a sampling effort of 90 trap-days. These records correspond to adult females, determined by the absence of testicles. Additionally, individuals were identified based on the fur coloration showing the characteristic disruptive pattern, where the nape and head are lighter-colored than the rest of the body (Presley 2000; Matos 2018). The first record was captured on 24 March 2023 at 14:12 hr, at coordinates 20°0’8.93” N and 97°42’51.60” W, at 835 m (Figure 3a). The second record was captured on 2 April 2023 at 06:53 hr, at coordinates 20°0’40.84” N and 97°42’51.60” W, at 1011 m (Figure 3b). Both records were obtained in remnants of mountain cloud forest within a matrix of shaded coffee plantations. One photographic record of an adult of G. vittata was also captured on 15 April 2023 at 15:50 hr, at coordinates 20°0’43.64” N and 97°43’10.86” W, at 840 m in the town of Zapotitlán de Méndez, in a stream running across a shaded-coffee plantation. The photographic shot does not allow determining the sex (Figure 3c, d), but it shows the coloration pattern of the species, i.e., blackish marbled gray on the back, in addition to small limbs and a short tail (Álvarez-Castañeda and González-Ruiz 2017).

Eira barbara is included in the lists of mammals for the state of Puebla (Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2005; Ramírez-Bravo 2011); however, there are few documented reports of its presence in a large part of the state (Table 1). In the Northern Sierra of Puebla, Ramírez-Bravo (2011) documented the presence of E. barbara in fragments of tropical vegetation in the municipality of Zihuateutla. Although its presence in this region of Puebla had not been confirmed recently, this study documented E. barbara in a fragment of cloud forest surrounded by shaded coffee plantations.

It has been observed that E. barbara occurs mainly in areas with primary vegetation or, at least, with a similar structure, although it is also found in landscapes modified by anthropic activities (Dotta and Verdade 2011; Timo et al. 2014), including agroforestry plantations (Soley and Alvarado-Díaz 2011). However, when landscape complexity is reduced, such as in coffee plantations without tree strata or when human disturbance increases, arboreal and scansorial mammals such as E. barbara can be negatively affected (Gallina et al. 1996; Naughton-Treves et al. 2003; Cassano et al. 2014).

The record of G. vittata in a stream coincides with other observations of this species reported by Gallina et al. (1996) and Sáenz-Bolaños et al. (2009). These authors point out that G. vittata thrives on the edges of dense forests, preferably near water bodies such as rivers or streams, although it has also been observed in areas with secondary and managed vegetation (De la Torre et al. 2009; Lucas-Juárez et al. 2021; Sánchez-Brenes and Monge 2022). In the Northeastern Sierra of Puebla, the presence of Grison has been reported in shaded coffee plantations in the Tecolutla River basin (Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2005; Ramírez-Bravo and Hernández-Santin 2016; Hernández-Reyes et al. 2017; Lucas-Juárez et al. 2021; Hernández-Hernández et al. 2022; Table 1).

Some studies have been carried out that analyzed population density (Hernández-Sánchez et al. 2017), diversity (Hernández-Hernández and Chávez 2021), and diet (Hidalgo-Mihart et al. 2018), which include few records of G. vittata; in other studies of diversity and activity patterns, this species was not recorded in conserved areas (Ortiz-Lozada et al. 2017; Ríos-Solís et al. 2021). In this sense, it is considered that anthropic factors such as habitat destruction and collision with vehicles can affect their populations (Escobar-Lasso and Guzmán-Hernández 2013; Salcedo-Rivera et al. 2020; García-Morales and Diez de Bonilla-Cervantes 2021). However, García-Morales and Diez de Bonilla-Cervantes (2021) point out that G. vittata is highly adaptable to modified environments and has the potential to maintain breeding populations in urban areas.

This study recorded G. vittata and E. barbara in fragments of mountain cloud forest surrounded by shaded coffee plantations. It has been pointed out that diversified shaded coffee plantations are a habitat that may have less impact on biodiversity compared to other activities such as livestock raising and rainfed or permanent cultivation (Greenberg et al. 1997; Cruz-Lara et al. 2004), which has probably allowed the presence of threatened species such as G. vittata and E. barbara in the Northeastern Sierra of Puebla (Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2005; Ramírez-Bravo and Hernández-Santin 2016). In this region, shaded coffee plantations are the predominant livelihood in the agricultural sector (Evangelista-Oliva et al. 2010). In this regard, components with buffer capacity, such as shaded coffee plantations, have corridors and vegetation fragments with significant inner habitat areas (Gallina et al. 1996), which should be prioritized in conservation strategies because they could serve as core reserves and maintain functional connectivity of the study area. However, additional studies are needed to determine whether these species can persist in highly anthropized environments (García-Morales and Diez de Bonilla-Cervantes 2021).

The records of E. barbara and G. vittata in the Northeastern Sierra of Puebla are relevant because they allow for determining the continuity of their distribution in the Sierra Madre Oriental. Their record in the north of the state could indicate that this region functions as a biological corridor between vegetation remnants in eastern and southeastern Mexico, including the Sierra Negra in Oaxaca and Veracruz. This area was also identified as essential for the dispersal of other carnivore species (Grigione et al. 2009; Ramírez-Bravo et al. 2010; Hernández-Flores et al. 2013; Dueñas-López et al. 2015). Additionally, the records of G. vittata and E. barbara in the Northeastern Sierra of Puebla provide relevant information to advance a better understanding of the distribution of populations of these species.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out thanks to the UNAM-PAPIIT Program IA206221. We thank H. Rojas Luis and J. Rodríguez Vázquez for their support in the fieldwork. María Elena Sánchez-Salazar translated the manuscript into English.

Literature cited

Álvarez-Castañeda, S. T. and N. González-Ruiz. 2017. Keys for identifying Mexican mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, U.S.A.

Álvarez del Toro, M. 1991. Los Mamíferos de Chiapas. Segunda edición. Consejo Estatal de Fomento a la Investigación y Difusión de la Cultura. Chiapas, México.

Arita, H. T. et al. 1990. Rarity in Neotropical Forest mammals and its ecological correlates. Conservation Biology 4:181-192.

Bisbal, E. 1986. Food habits of some Neotropical carnivores in Venezuela (Mammalia, Carnivora). Mammalia 50:329-340.

Bornholdt, R. et al. 2013. Taxonomic revision of the genus Galictis (Carnivora: Mustelidae): species delimitation, morphological diagnosis, and refined mapping of geographical distribution. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 167:449-472.

Cassano, C. R. et al. 2014. Forest loss or management intensification? Identifying causes of mammal decline in cacao agroforests. Biological Conservation 169:14-22.

Ceballos, G. and G. Oliva. 2005. Los Mamíferos Silvestres de México. Conabio-Fondo de Cultura Económica. México, D. F.

Chávez, C. 2005. Eira barbara. Pp. 376-378 in Los mamíferos silvestres de México (Ceballos, G. and G. Oliva, eds.). CONABIO–UNAM–Fondo de Cultura Económica, México D.F.

Chávez-León, G. 1987. Mamíferos del sur de Quintana Roo, México. Revista Ciencia Forestal 62:91-116.

Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO). 2020. Sistema Nacional de Información sobre Biodiversidad. Registros de ejemplares. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. Ciudad de México, México. https://www.snib.mx/taxonomia/descarga/. Accessed on 12 September 2024.

Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO). 2011. La biodiversidad en Puebla: estudio de estado. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Gobierno del estado de Puebla, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, México. https://bioteca.biodiversidad.gob.mx/janium-bin/detalle.pl?Id=20241116064502. Accessed on 25 September 2024.

Contreras-Díaz, C. et al. 2020. Expansion of distribution range of the Greater Grison (Galictis vittata) in Mexico. Therya Notes 1:1-4.

Contreras-Moreno, F. M. et al. 2023. Nuevos registros del grisón (Galictis vittata) en Campeche, México. Therya Notes 4:21-26.

Cruz-Lara, L. C. et al. 2004. Diversidad de mamíferos en cafetales y selva mediana de las cañadas de la Selva Lacandona, Chiapas, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana 20:63-81.

De la Torre, J. A. et al. 2009. Nuevos registros de grisón (Galictis vittata) para la selva Lacandona, Chiapas, México. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología (Nueva Época) 13:109-114.

Dotta, G. and L. M. Verdade. 2011. Medium to large-sized mammals in agricultural landscapes of southeastern Brazil. Mammalia 75:345-352.

Dueñas-López, G. et al. 2015. Connectivity among jaguar populations in the Sierra Madre Oriental, México. Therya 7:449-468.

Escobar-Lasso, S. and C. F. Guzmán-Hernández. 2014. El registro de mayor altitud del Hurón Mayor Galictis vittata, con notas sobre su presencia y conservación dentro del departamento de Caldas, en la región andina de Colombia. Therya 5:567-574.

Espinosa-Lucas, A. et al. 2015. Tres nuevos registros en la zona de influencia de la Reserva de la Biosfera Tehuacán-Cuicatlán, Oaxaca. Therya 6:661-666.

Espinosa-Medinilla, E. E. et al. 2018. Registros adicionales de mamíferos silvestres en el área de aprovechamiento forestal: Los Ocotones Chiapas, México. Agrociencia 52:553-562.

Evangelista-Oliva, V. et al. 2010. Patrones espaciales de cambio de cobertura y uso del suelo en el área cafetalera de la sierra norte de Puebla. Investigaciones Geográficas 72:23-38.

Gallina, S. and A. González-Romero. 2018. La conservación de mamíferos medianos en dos reservas ecológicas privadas de Veracruz, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 89:1245-1254.

Gallina, S. et al. 1996. Conservation of mammalian biodiversity in coffee plantations of Central Veracruz, Mexico. Agroforestry Systems 33:13-27.

Gallo-Reynoso, J. P. 2013. Perspectiva histórica de las Nutrias en México. Therya 4:191-199.

García, J. J. et al. 2016. Registros del tayra (Eira barbara Linneanus 1758) en el estado de Hidalgo, México. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología (Nueva Época) 6:24-28.

García Morales, R. and B. B. Diez de Bonilla-Cervantes. 2021. Registro de Galictis vittata (Carnivora: Mustelidae) en un área suburbana en el estado de Tabasco, México. Mammalogy Notes 7:215.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). 2024. Free and open access to biodiversity data https://www.gbif.org/. Accessed on 10 August 2024.

González-Maya, J. F. et al. 2019. Predicting Greater Grison Galictis vittata presence from scarce records in the department of Cordoba, Colombia. Small Carnivore Conservation 57:34-44.

González-Varo, J. P. et al. 2015. Frugivoría y dispersión de semillas por mamíferos carnívoros: rasgos funcionales. Ecosistemas 24:43-50.

Greenberg, R. et al. 1997. Bird populations in shade and sun coffee plantations in Central America. Conservation Biology 11:448-459.

Grigione, M. M. et al. 2009. Identifying potential conservation areas for felids in the USA and Mexico: integrating reliable knowledge across an international border. Oryx 43:78-86.

Hernández-Flores, S. D. et al. 2013. First records of the Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) in the state of Hidalgo, Mexico. Therya 4:99-102.

Hernández-Hernández, J. C. et al. 2019. Nuevos registros de tayra (Eira barbara) y ocelote (Leopardus pardalis) en una selva baja caducifolia de Yucatán, México. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología (Nueva Época) 9:55-62.

Hernández-Hernández, J. C. and C. Chávez. 2021. Inventory of medium-sized and large mammals in La Encrucijada Biosphere Reserve and Puerto Arista Estuarine System, Chiapas, Mexico. Check List 17:1115-1170.

Hernández-Hernández, J. C. et al. 2022. Registros recientes del grisón (Galictis vittata) y el tigrillo (Leopardus wiedii) en la Sierra Nororiental de Puebla, México. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología (Nueva Época) 12:49-54.

Hernández-Reyes, E. et al. 2017. Patrones de cacería de mamíferos en la Sierra Norte de Puebla. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie) 33:421-430.

Hernández-Sánchez, A. et al. 2017. Abundance of mesocarnivores in two vegetation types in the southeastern region of Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist 62:101-108.

Hidalgo-Mihart, M. G. et al. 2018. Greater Grison (Galictis vittata) hunts a central American indigo snake (Drymarchon melanurus) in southeastern Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist 63:197-199.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2005. Guía para la interpretación de cartografía. Climatológica. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, México. https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825231781. Accessed on 8 September 2024.

Jiménez-Alvarado, S. et al. 2016. Análisis de la distribución del grisón (Galictis vittata) (Carnivora: Mustelidae) en el Caribe Colombiano. Therya 7:1-9.

Lavariega, M. C. and M. Briones-Salas. 2019a. Eira barbara (cabeza de viejo). Distribución potencial. Escala: 1:1000000. edición: 1. Centro Interdisciplinario de Investigación para el Desarrollo Integral Regional Unidad Oaxaca. Proyecto: JM011, Modelado de la distribución geográfica de mamíferos endémicos y en categoría de riesgo de Oaxaca. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO). Xoxocotlán, Oaxaca. http://www.conabio.gob.mx/informacion/gis/?vns=gis_root/biodiv/distpot/dpmamif/dpmcarni/eba011dpgw. Accessed on 10 September 2024.

Lavariega, M. C. and M. Briones-Salas. 2019b. Galictis vittata (grisón). Distribución potencial. Escala: 1:1000000. edición: 1. Centro Interdisciplinario de Investigación para el Desarrollo Integral Regional Unidad Oaxaca. Proyecto: JM011, Modelado de la distribución geográfica de mamíferos endémicos y en categoría de riesgo de Oaxaca. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO). Xoxocotlán, Oaxaca. http://www.conabio.gob.mx/informacion/gis/?vns=gis_root/biodiv/distpot/dpmamif/dpmcarni/gvi011dpgw. Accessed on 10 September 2024.

Larivière, S. and A. P. Jennings. 2009. Family Mustelidae. Pp. 564-656 in Handbook of the Mammals of the World: Carnivores (Wilson, D. E. and R. A. Mittermeier, eds.). Lynx Edicions. Barcelona, España.

López-Bao, J. V. and J. P. González-Varo. 2011. Frugivory and spatial patterns of seed deposition by carnivorous mammals in anthropogenic landscapes: a multi-scale approach. PloS One 6: e14569.

López-González, C. and D. Aceves-Lara. 2007. Noteworthy record of the tayra (Carnivora: Mustelidae: Eira barbara) in the Sierra Gorda Biosphere Reserve, Querétaro, Mexico. Western North American Naturalist 67:150-151.

Lucas-Juárez, G. et al. 2021. Nuevo registro del grisón mayor (Galictis vittata) en la Sierra Nororiental de Puebla, México. Therya Notes 2:47-50.

Mejenes-López, S. et al. 2010. Los mamíferos en el estado de Hidalgo. Therya 3:161-188.

Mendoza, E. et al. 2023. Impacts of land use and cover change on land mammal distribution ranges across Mexican ecosystems. Pp. 270-283 in Mexican Fauna in the Anthropocene (Jones, C. et al., eds.). Springer Nature, Switzerland.

Nagy‐Reis, M. et al. 2020. Neotropical Carnivores: a data set on carnivore distribution in the Neotropics. Ecology 101:e03128.

Naughton-Treves, L., et al. 2003. Wildlife survival beyond park boundaries the impact of slash-and-burn agriculture and hunting on mammals in Tambopata, Peru. Conservation Biology 17:1106-1117.

Nowak, R. M. 2005. Walker’s carnivores of the world, sixth edition. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, EE. UU.

Oliveira, T. G. 2009. Notes on the distribution, status, and research priorities of little-known small carnivores in Brazil. Small Carnivore Conservation 41:22-24.

Ortiz-Lozada, L. et al. 2017. Absence of large and presence of medium-sized mammal species of conservation concern in a privately protected area of rainforest in Southeastern Mexico. Tropical Conservation Science 10:1-13.

Pérez-Solano, L. A. et al. 2018. Mamíferos medianos y grandes asociados al bosque tropical seco del centro de México. Revista de Biología Tropical 66:1232-1243.

Presley, S. J. 2000. Eira barbara. Mammalian Species 636:1-6.

Ramírez-Bravo, O.E. et al. 2010. Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) distribution in the state of Puebla, Central Mexico. Therya 1:111-20.

Ramírez-Bravo, O. E. 2011. New records of tayra (Eira barbara Linnaeus 1758) in Puebla, central Mexico. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie) 27:883-886.

Ramírez-Bravo, O. E. and L. Hernández-Santin. 2016. Carnivores (Mammalia) from areas of Nearctic-Neotropical transition in Puebla, central Mexico: Presence, distribution, and conservation. Check List 12:1833.

Ramírez Pulido, J. et al. 2005. Carnivores from the mexican state of Puebla: distribution, taxonomy and conservation. Mastozoología Neotropical 12:37-52.

Ríos-Solís, J. A. et al. 2021. Diversity and activity patterns of medium- and large-sized terrestrial mammals at the Los Tuxtlas Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Therya 12:237-248.

Roemer, G. W. et al. 2009. The ecological role of the mammalian mesocarnivore. Bioscience 59:165-173.

Ruiz-Gutiérrez, F. et al. 2017. Range expansion of a locally endangered mustelid (Eira barbara) in Southern Mexico. Western North American Naturalist 77:408-413.

Sáenz-Bolaños, C. et al. 2009. Presencia de Galictis vittata (Carnivora: Mustelidae) en el Caribe Sur y Pacífico Norte de Costa Rica. Brenesia 71-72.

Salcedo-Rivera, G. A. et al. 2020. Recent confirmed records of Galictis vittata in the department of Sucre, Caribbean region of Colombia. Therya Notes 1:86-91.

Sánchez-Brenes, R. and J. Monge. 2022. The grison, Galictis vittata (Carnivora: Mustelidae) in coffee agroecosystems, Costa Rica. UNED Research Journal 14:e3796.

Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT). 2010. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010, Protección ambiental-Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres-Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio-Lista de especies en riesgo. Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. México. 30 December 2010. México City, México.

Servín, J. 2013. Perspectivas de estudio, conservación y manejo de los Carnívoros en México. Therya 4:527-430.

Soley, F. G. and I. Alvarado-Díaz. 2011. Prospective thinking in a mustelid? Eira barbara (Carnivora) cache unripe fruits to consume them once ripened. Naturwissenschaften 98: 693-698.

Sosa-Escalante, J. E. et al. 2013. Mamíferos terrestres de la península de Yucatán, México: riqueza, endemismo y riesgo. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 84:949-969.

Srbek-Araujo, A. C. and A. Garcia-Chiarello. 2005. Is camera-trapping an efficient method for surveying mammals in Neotropical forests? A case study in southeastern Brazil. Journal of Tropical Ecology 21:121-125.

Sunquist, M. E. et al. 1989. Ecological separation in a Venezuelan llanos carnivore community. Pp. 197-232 in Advances in Neotropical mammalogy (Redford, K. H. and J. F. Eisenberg, eds.). Sandhill Crane Press, Florida, EE. UU.

Timo, T. P. C. et al. 2014. Effect of the plantation age on the use of eucalyptus stands by medium to large-sized wild mammals in southeastern Brazil. iForest 8:108-113.

Tobler, M. W. et al. 2008. An evaluation of camera traps for inventorying large‐and medium‐sized terrestrial rainforest mammals. Animal Conservation 11:169-178.

Villafañe-Trujillo, A. J. et al. 2021. Activity patterns of tayra (Eira barbara) across their distribution. Journal of Mammalogy 102:772-788.

Wilson, D. E. and D. M. Reeder (eds). 2005. Mammal species of the World. A taxonomic and geographic reference, third edition. Johns Hopkins Press. Baltimore, EE. UU.

Wilson, D. E. and R. A. Mittermeier. 2009. Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Carnivores. Lynx Edicions. Barcelona, España.

Yensen, E. and T. Tarifa. 2003. Galictis vittata. Mammalian Species 727:1-8.

Associated Editor: Jorge Ayala Berdón.

Submitted: November 8, 2024; Reviewed: Febrary 12, 2025.

Accepted: March 16, 2025; Published on line: june 23, 2025.