THERYA NOTES 2026, Vol. 7: 1-5

A new record of hypodontia in Phyllostomus discolor

with notes on its evolutionary implications

Un nuevo registro de hipodoncia en Phyllostomus discolor

con notas sobre sus implicaciones evolutivas

Valentino Juárez1,2*, Maria João Ramos Pereira2,3, Carlos Aya-Cuero4, and Diego A. Esquivel2,4

1Programa de Pós-Graduação em Genética e Biologia Molecular, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Av. Bento Gonçalves, 9090, Porto Alegre-RS, Brasil. E-mail: vjs.cambara@yahoo.com.br (VJ).

2Bird and Mammal Evolution, Systematics and Ecology Lab, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Av. Bento Gonçalves, 9090, Porto Alegre-RS, Brasil. E-mail: maria.joao@ufrgs.br (MJRP).

3Centre for Environmental and Marine Studies, Universidade de Aveiro (UA), Campus Universitario de Santiago. Aveiro, Portugal.

4Fundación Kurupira, Bogotá D. C., DIAGONAL 16 B 106 65, Colombia. E-mail: caya@unal.edu.co (CA-C); diegodaem@gmail.com (DAE).

*Corresponding author

Dental anomalies are disruptions in the normal development of teeth, primarily caused by genetic mutations, leading to variations in the number, shape, size, eruption, and formation of hard tissues. Although these abnormalities have been observed in various mammalian groups, their incidence and implications remain underexplored. We identified one specimen of Phyllostomus discolor with a dental anomaly. Following this discovery, we made a review of dental anomalies in Chiroptera searching for specific terms related to bats and dental anomalies and then conducted a linear regression to detect the trend of publications. Here, we report a new record of hypodontia in the Pale Spear-nosed bat Phyllostomus discolor. The hypodontia was identified in a male specimen of the Pale Spear-nosed bat from the Andean region of Colombia, characterized by a missing incisor adjacent to internal incisors in the mandible, resulting in three lower incisors—one fewer than normal. Understanding the patterns, incidence, and variations of dental anomalies across mammalian clades can enhance taxonomic studies and elucidate the mechanisms driving dental trait diversification. However, we highlight a low interest in publications barely averaging 0.73 reports per year. Contrary to what was expected, and unlike other genetic, eco-devo and evolutionary approaches used to investigate mammalian teeth, we evidence a clear reduction and possible lack of interest in this topic. We urge researchers and curators to document such anomalies that allow to challenge current hypotheses about their occurrence and evolutionary implications.

Key words: Bats; dental anomalies; developmental bias; hypodontia; tooth variation.

Las anomalías dentales son alteraciones en el desarrollo normal de los dientes, causadas principalmente por mutaciones genéticas, que provocan variaciones en el número, forma, tamaño, erupción y la formación de los tejidos duros. Aunque estas anomalías se han observado en diversos grupos de mamíferos, su incidencia e implicaciones siguen siendo poco exploradas. Se identificó un ejemplar de Phyllostomus discolor con una anomalía dental. Tras este descubrimiento, se realizó una revisión de las anomalías dentales en quirópteros buscando términos específicos relacionados con murciélagos y anomalías dentales, y posteriormente se realizó una regresión lineal para detectar la tendencia de las publicaciones. Reportamos un nuevo registro de hipodoncia en el murciélago Phyllostomus discolor. La hipodoncia se identificó en un ejemplar macho de murciélago de nariz de lanza pálida de la región andina de Colombia, caracterizado por la ausencia de un incisivo adyacente a los incisivos internos de la mandíbula, lo que resulta en tres incisivos inferiores, uno menos de lo normal. Comprender los patrones, la incidencia y las variaciones de las anomalías dentales en los clados de mamíferos puede enriquecer los estudios taxonómicos y aclarar los mecanismos que impulsan la diversificación de los rasgos dentales. Sin embargo, destacamos el bajo interés en las publicaciones, con un promedio de apenas 0,73 registros publicados al año. Contrariamente a lo esperado, y a diferencia de lo que ocurre con otros enfoques genéticos, de eco-devo y evolutivos utilizados para investigar los dientes de mamíferos, evidenciamos una clara reducción y posible falta de interés en este tema en particular. Recomendamos a investigadores y curadores a documentar estas anomalías que permitan cuestionar las hipótesis actuales sobre su ocurrencia e implicaciones evolutivas.

Palabras clave: Anomalías dentales; dentición; murciélago; sesgo del desarrollo; variación dental.

Dental development is tightly regulated by genetic mechanisms that ensure the formation, growth and replacement of a specific number of teeth with precise shapes and positions in each species (Yu and Klein 2020; Yamanaka 2022). However, mutations in certain genes can disrupt this normal development, leading to anomalies in tooth number, shape, size, eruption, internal structure, or the formation of hard tissues such as enamel, dentin, or cementum (Thesleff 2000). These deviations, commonly known as dental anomalies (Wolsan 1984), have been observed in a diverse range of mammalian groups, including primates (both humans and non-human species; Bateson 1892), pinnipeds (Drehmer, 2015), pilosans (e.g., sloths; McAfee 2014), marsupials (such as opossums; Martin and Chemisquy 2018), felids (Gomercič et al. 2009), and bats (López-Aguirre 2014; Esquivel et al. 2017). Despite the different types of dental anomalies that can affect mammals (Table 1), the incidence and prevalence of dental anomalies are possibly much higher has been reported up to now, as many cases that have likely gone not published. Even with the fact that dental anomalies have not gone unnoticed by scientists (Phillips 1971; Rui and Drehmer 2004), little interest has been given to their recording and implications. Traditionally, dental anomalies have been thought to be relatively rare phenotypes resulting from poorly understood genetic, environmental, or developmental processes (McAfee 2014). However, such anomalies may present the principal source of morphological variation in the teeth upon which natural selection may operate. A modern phylogenetic analysis on a dataset derived from 17,905 observations, examined the patterns of dental anomalies across bats, and tested for potential ecological and structural factors associated with the incidence of dental anomalies in this group (Esquivel et al. 2021). Remarkably, these authors found that dental anomalies have a significant phylogenetic signal, suggesting that they are not simply the result of random mutations or developmental disorders, but susceptibility may have genetic underpinnings resulting from shared developmental pathways among closely related species.

The presence of this lineage-specific patters produces a developmental bias, that can drive morphological evolution in specific directions through nonrandom phenotypic transitions (Brigandt 2020). Intrinsic developmental differences between lineages, alongside selective pressures, are crucial factors in this process (Brown 2014). For instance, if some phenotypes, like hypodontia, are more likely to arise spontaneously than others, such as hyperdontia, this may drive dental trait evolution (Brigandt 2020; Esquivel et al. 2021). This influence is relevant even in traits under selection, making some lineages more likely to change in response to new selective pressures (Brown 2014).

A deeper understanding of odontogenesis (tooth formation) can provide insights about occurrence of dental anomalies in mammals (Thesleff 2000; Bei 2009; Juuri and Balic 2017). Odontogenesis involves over 300 genes and more than 100 transcription factors (Bei 2009). However, there are no known genes for a specific tooth class, instead, different combinations of genes are involved (Wakamatsu et al. 2019). In addition, tooth formation results from interactions between two embryonic tissues: the ectodermal epithelium (dental lamina) and ectomesenchyme (Mitsiadis and Smith 2006). Therefore, dental anomalies are a complex phenomenon related to various genetic factors and regulatory pathways. There are four main pathways that not only regulate odontogenesis but also interact with each other (Zhang 2023). The WNT signaling pathway plays a critical role in the initiation and morphogenesis stages; the Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) pathway is involved in the establishment of the dental field and the specification of tooth identity; the Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) pathway is essential for the regulation of mesenchymal-epithelial interactions; the Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) pathway plays a role in the regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation (Zhang 2023).

Knockout/knockdown mice studies reveal the relationships between these pathways and tooth phenotypes. For example, mutations in the SOSTDC1 gene (a WNT inhibitor) result in supernumerary teeth (Hermans et al. 2021), while mutations in GLI2 (a SHH activator) cause absent teeth (Hermans et al. 2021). These pathways are promising candidates for studying tooth anomalies and normal phenotypic variation within and among species.

Here, we present a new record of dental anomaly in Phyllostomus discolor, advancing knowledge on these types of anomalies in the Phyllostomidae family. We also discuss temporal trends in publications, and interest among the scientific community.

During a taxonomic review of the neotropical bat genus Phyllostomus, we identified one specimen of Phyllostomus discolor (out of 260 analyzed) housed at the Instituto de Ciencias Naturales (ICN, Bogotá D. C., Colombia) with a dental anomaly in the mandible and take its morphometric measurements (in mm) are as follows: forearm (AB), total length (TL), ear length (E), foot length (FL), greatest length of skull (GLS), condyloincisive length (CIL), condylocanine length (CCL), zygomatic breadth (ZB), postorbital breadth (PB), palatal length (PL), and dentary length (DENL). Following this discovery, we reanalyzed the data from Esquivel et al. (2021) on publications about dental anomalies in bats, and updated it to identify temporal trends. We surveyed databases such as Google Scholar, ISI Web of Knowledge, Scopus, Biodiversity Heritage Library, and institutional repositories using keywords in Spanish, English, and Portuguese: “Bat” OR “Chiroptera” AND “dental anomalies”, “abnormal”, “extra teeth”, “hyperdontia”, “oligodontia”, “polyodontia”, “supernumerary teeth”, “hypodontia”, and “dental variation”. We calculated the number of publications per year and conducted a linear regression to test the hypothesis that research on this topic follows a positive trend, with an increasing number of publications over consecutive decades. All our analyses were performed using R software (R Core Team 2024).

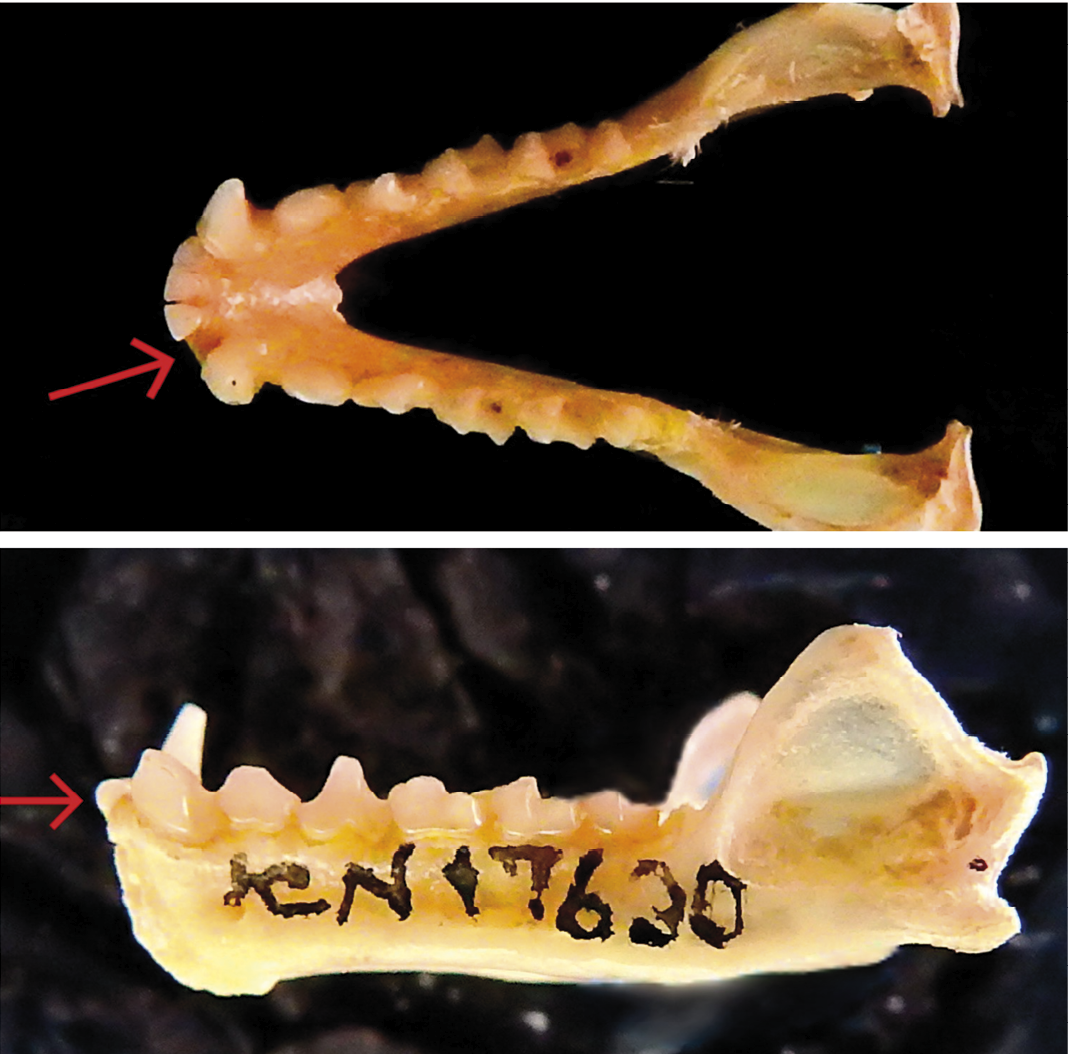

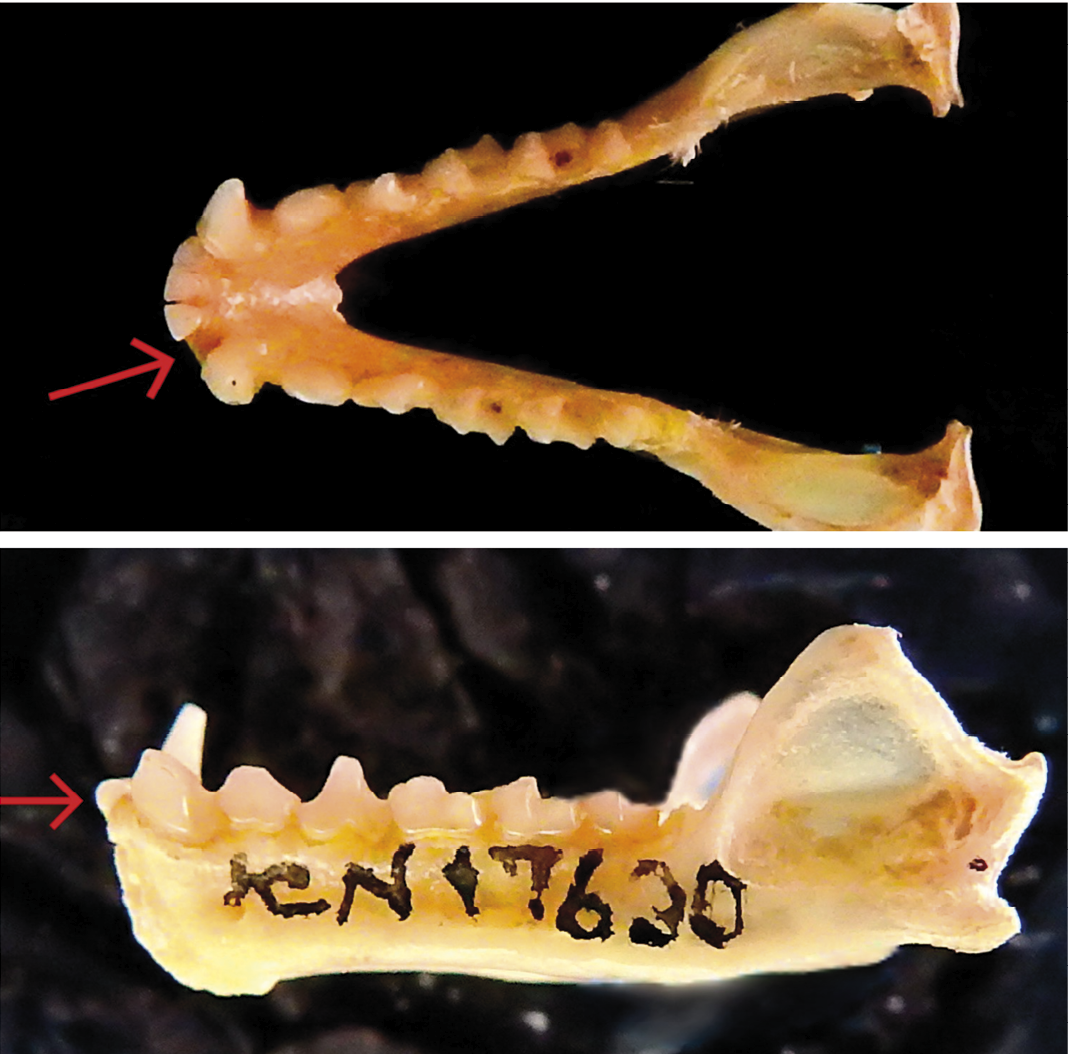

The dental anomaly is reported from the specimen ICN 17630 which has a missing lateral incisor (I2) in the mandible, without alveoli, resulting in a total of 3 lower incisors in each side of the mandible– one fewer than normal (Figures 1 and 2). This specimen is an adult male, exhibiting cranial sutures with advanced degree of ossification and little wear on the tooth cusps. Its morphometric measurements (in mm) are as follows: AB = 63.95, TL = 94, E = 22, FL = 16, GLS = 31.3, CIL = 28.2, CCL = 26.3, ZB = 16.6, PB = 6.9, PL = 13.9, and DENL = 19.9. This individual was collected by M. E. Rodriguez, P. A. Otalora, A. Camargo on July 09, 2001, in Ocamonte, Santander, Colombia. The lack of a dental socket, combined with the number of incisors and minimal dental wear, leads us to conclude that the anomaly is hypodontia, instead of the loss by a traumatic event.

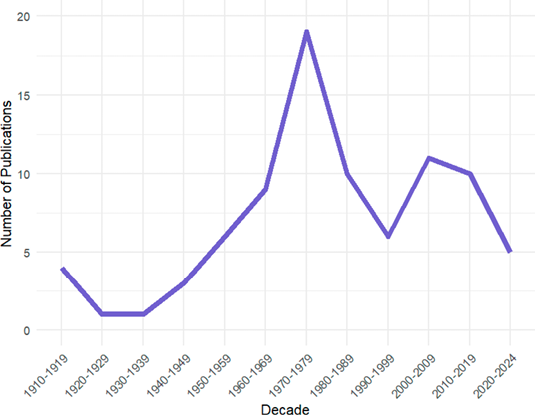

From our survey, we found 85 publications (Figure 2) reporting dental anomalies in bats along 114 years. The number of publications vary across different decades, though it is apparent that research in this area has been relatively sparse, with a rate of 0.73 publications per year. Each decade shows values ranging between 5 to 18 of publications, highlighting a significant underrepresentation in the scientific literature. Although there was a slight increase in the 1980s, this trend has not been sustained. In fact, the number of publications has been declining steadily since the 1990s (Figure 2). Our regression analysis confirms that statement. The p-value indicates that the year is not a statistically significant predictor of the number of publications (P > 0.05) showing no increase in the number of publications over consecutive decades.

Our record of hypodontia in Phyllostomus discolor is the second documented case for this species. The first observation was reported by Polaco et al. (1992), who identified an individual from Mexico missing the second upper premolar (P4). This new finding not only augments the known reports within Phyllostomus but also contributes to the broader dataset of dental anomalies within the Phyllostomidae family, which currently includes 50 species exhibiting these type of anomalies (Esquivel et al. 2021). The standard dental formula for Phyllostomus is 2/2, 1/1, 2/2, 3/3 × 2 = 32 (Williams and Genoways, 2007). Notably, our report marks the first incidence of hypodontia affecting an incisor in this genus.

This dental anomaly may be attributable to an isolated mutation present in this individual that reduces the odontogenic potential of the continuous lamina causing punctual tooth loss (Juuri and Balic 2017). The lack of similar anomalies in other specimens from the study area suggests that this is an uncommon mutation within the population (Colombia, Santander, Ocamonte, Finca Macanal, Cueva la Virgen; 1,290 m, 6° 17’ 47” N, 73° 8’ 19” W). Notably, the occurrence of dental anomalies in Chiroptera is approximately 4.65 % (Esquivel et al. 2021), so while its occurrence is considered rare, it is actually a phenomenon that may be more common than thought.

Further research could involve identifying the genetic basis of dental anomalies in bats and other mammals, which could enhance our understanding of the evolution of teeth as well as other related traits. Moreover, comparative studies among different taxa could highlight the existence of phylogenetic signals and shed light on the mechanisms underlying the diversification of dental traits (Sadier et al. 2023; Marrelli 2024). Understanding patterns and incidence of dental anomalies, as well as their variations across different clades, might also be of value for taxonomic studies in bats and other mammals. Despite its importance, it is concerning that the attention to documenting dental anomalies has declined in recent years. Indeed, 71 % of reports on dental anomalies in bats were published before the year 2000. In contrast, only one such report on average has been published per year over the past 24 years. Therefore, we earnestly call for increased reporting of these anomalies, given the current hypotheses about their incidence and their potential to contribute to our understanding of dental evolution in mammals. By documenting and analyzing these dental anomalies, we can contribute to a better understanding of their prevalence and implications.

Acknowledgements

The first author gratefully acknowledges the support of the Institutional Program for Scientific Initiation Scholarships (PROBIC), funded by the Research Support Foundation of the State of Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS) and the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). The author also extends sincere appreciation to the professors who contributed to this journey and to his parents, Maria and Juarez, for their endless support. Additionally, the author thanks the reviewers for their thoughtful feedbackand valuable suggestions, which greatly contributed to the improvement of this work.

Literature cited

Bateson, W. 1892. On numerical variation in teeth, with a discussion of the conception of homology. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. London, United Kingdom.

Bei, M. 2009. Molecular genetics of tooth development. Current opinion in genetics & development 19:504–510.

Brigandt, I. 2020. Historical and philosophical perspectives on the study of developmental bias. Evolution & Development 22:7–19.

Brown, R. L. 2014. What evolvability really is. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 3:1–24.

Drehmer, C., D. Jaeger, D. Sanfelice, And C. Loch. 2015. Dental anomalies in pinnipeds (Carnivora: Otariidae and Phocidae): occurrence and evolutionary implications. Zoomorphology 134:325–338.

Esquivel, D. A., D. Camelo-Pinzón, and A. Rodríguez-Bolaños. 2017. New record of bilateral hyperdontia in Carollia brevicauda (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae). Therya 8:71–73.

Esquivel, D. A., R. Maestri, And S. E. Santana. 2021. Evolutionary implications of dental anomalies in bats. Evolution 75:1087–1096.

Gomerčić, T., et al. 2009. Variation in teeth number, teeth and skull disorders in Eurasian Lynx, Lynx lynx from Croatia. Folia Zoológica 58:57–65.

Hermans, F., et al. 2021. Intertwined signaling pathways governing tooth development: a give-and-take between canonical Wnt and Shh. Frontiers in cell and Developmental biology 9:758203.

Juuri, E., and A. Balic. 2017. The biology underlying abnormalities of tooth number in humans. Journal of Dental Research 96:1248–1256.

López-Aguirre, C. 2014. Dental anomalies: new cases of Artibeus lituratus from Colombia and a review of these anomalies in bats (Chiroptera). Chiroptera Neotropical 20:1271–1279.

Marrelli, M. S., et al. 2024. Dental abnormalities in Myotis riparius (Chiroptera, Vespertilionidae), with comments on its evolutionary implications. Mammalia 88:33-36.

Martin, G. M., and M. A. Chemisquy. 2018. Dental anomalies in Caluromys (Marsupialia, Didelphimorphia, Didelphidae, Caluromyinae) and a reassessment of malformations in New World marsupials (Didelphimorphia, Microbiotheria and Paucituberculata). Mammalia 82:500–508.

Mcafee, R. K. 2014. Dental anomalies within extant members of the mammalian Order Pilosa. Acta Zoologica 96:301–311.

Mitsiadis, T. A., and M. M. Smith. 2006. How do genes make teeth to order through development? Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 306:177–182.

Polaco, O. J., J. Arroyo-Cabrales, and J. K. Jr. Jones. 1992. Noteworthy records of some bats from Mexico. Texas Journal of Science 44:332–338.

Phillips, C. J. 1971. The dentition of Glossophaginae bats: development, morphological characteristics, variation, pathology, and evolution. University of Kansas. Lawrence, EE. UU.

R Core Team. 2024. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. Available via http://www. R-project. org/

Rui, A. M., and C. J. Drehmer. 2004. Anomalies and variation in the dental formula of bats of the genus Artibeus Leach (Chiroptera, Phyllostomidae). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 21:639–648.

Sadier, A., et al. 2023. Bat teeth illuminate the diversification of mammalian tooth classes. Nature Communications 14:4687.

Smith, J. M., et al. 1985. Developmental constraints and evolution: a perspective from the Mountain Lake conference on development and evolution. The Quarterly Review of Biology 60: 265–287.

Thesleff, I. 2000. Genetic basis of tooth development and dental defects. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica 58:191–194.

Wakamatsu, Y., et al. 2019. Homeobox code model of heterodont tooth in mammals revised. Scientific Reports 9:12865.

Williams, S. L., and H. H. Genoways. 2007. Subfamily Phyllostominae Gray, 1825. In A. L. Gardner (ed.) Mammals of South America. Volume 1 Marsupials, Xenarthrans, Shrews, and Bats. The University of Chicago Press.

Wolsan, M. 1984. The origin of extra teeth in mammals. Acta Theriologica 29:128–133

Yamanaka, A. 2022. Evolution and development of the mammalian multicuspid teeth. Journal of Oral Biosciences 64:165–175.

Yu, T., and O. D. Klein. 2020. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of tooth development, homeostasis and repair. Development 147:dev184754.

Zhang, H., et al. 2023. Tooth number abnormality: from bench to bedside. International Journal of Oral Science 15:5.

Associate editor: José Fernando Moreira Ramírez

Submitted: January 8, 2025; Reviewed: August 25, 2025;

Accepted: October 28, 2025; Published on line: January 22, 2025.

© 2026 Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología, www.mastozoologiamexicana.org

DOI: 10.12933/therya_notes-24-219

ISSN 2954-3614

Table 1. Classification and diagnosis of the main dental anomalies that can affect bats and other mammals.

|

What type of dental anomaly is it? |

||

|

Category |

What name to use? |

When to use? |

|

By Number |

Anodontia |

Total lack of development of teeth (same as agenesis of teeth). |

|

Hypodontia |

Having less than six missing teeth. |

|

|

Oligodontia |

Six or more missing teeth. |

|

|

Hyperdontia |

One or more extra teeth. Also called supernumerary teeth or Polyodontia. |

|

|

By Size |

Microdontia |

Teeth that are smaller than normal. At least 40% or more. |

|

Macrodontia |

Teeth that are larger than normal. At least 40% or more. |

|

|

By Position |

Transposition |

Interchange in the position of two adjacent permanent teeth. |

|

Transmigration |

Movement of an impacted tooth across the jaw midline. |

|

|

Diastema |

Presence of an abnormal space between two adjacent teeth. |

|

|

By Eruption |

Ectopic |

A tooth that erupts or develops in an abnormal position outside of the normal dental arch. |

|

Impaction |

A condition where a tooth fails to fully emerge through the gum line and remains partially or completely trapped beneath the gum tissue and/or bone. |

|

|

Retained |

A tooth that persists in the oral cavity beyond its expected time of exfoliation or replacement, failing to shed according to the normal timeline of dental development for the species. |

|

|

By Morphology |

Germination |

A single tooth germ attempts to divide into two, resulting in the formation of an oversized tooth with two distinct crowns. This is a type of “Double tooth” or “connate tooth”. |

|

Fusion |

Two adjacent tooth germs fuse together, resulting in the formation of a single, larger tooth structure. This is a type of “Double tooth” or “connate tooth”. |

|

|

Talon cusp |

Cusp-like structure projecting from the cingulum area or lingual surface of an anterior tooth, commonly the maxillary lateral incisor. This extra cusp resembles a talon and can vary in size and shape. |

|

|

Dens evaginatus |

Abnormal tubercle or cusp-like projection arising from the occlusal surface of a premolar tooth. |

|

|

Dens invaginatus |

Deep invagination of the crown or root surface covered by enamel. |

|

|

Concrescence |

Two or more adjacent teeth become fused together by cementum. |

|

|

Taurodontism |

Elongation of the pulp chamber in a tooth, resulting in an enlarged pulp chamber and shortened roots. |

|

|

Dilaceration |

An abnormal and abrupt deviation in the root of a tooth. |

|

|

Enamel Pearl |

A small, spherical or globular formation of excess enamel on the surface of a tooth. |

|

Figure 1. Lateral (A) and occlusal view (B) of the mandible of specimen ICN 5913♂, detailing the missing incisor.

Figure 2. Historical trend of publications on dental anomalies in bats.