THERYA NOTES 2024, Vol. 5 : 268-272 DOI: 10.12933/therya_notes-24-184 ISSN 2954-3614

Predation attempt of Phyllostomus hastatus on Artibeus jamaicensis in Panamá

Intento de depredación de Phyllostomus hastatus sobre Artibeus jamaicensis en Panamá

Nelson Guevara1*, Lorena Romero2, Hilary Peralta2, Emily Martínez2, Thiana Alvarado1, 2, Yosari Cáceres1, 2, and Mallory Salgado1, 2

1Grupo de Investigación, Fundación Biomundi. Brisas del Lago, Los Pilones, 24 de Diciembre, C. P. 07109, Provincia de Panamá. Ciudad de Panamá, Panamá. E-mail: nelson2295@hotmail.com (NG); thianapaola@gmail.com (TA); giorenix36@gmail.com (YC); mallorysalgado04@gmail.com (MS).

2Escuela de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Exactas y Tecnología, Universidad de Panamá, Campus Central Octavio Méndez Pereira. Vía Transístmica, C. P. 07096, Provincia de Panamá. Ciudad de Panamá, Panamá. E-mail: lvromero0419@gmail.com (LR); hilaryprlt@gmail.com (HP); emilymarie13@gmail.com (EM).

*Corresponding author

The family Phyllostomidae includes the species Phyllostomus hastatus, which is distinguished by its large size and wide distribution; it is an omnivorous bat that feeds mainly on invertebrates and fruits. However, there are reports of predation on small vertebrates, such as bats, of which the cases documented in the scientific literature are usually few. Using 2 5-ring mist nets, 12 m long by 2.5 m wide, placed mainly at ground level on the banks of the Pedro Miguel River, in an area of secondary tropical lowland vegetation, captures were made by monitoring the abundance and richness of bats in Camino de Cruces National Park. On July 30, 2024, in Camino de Cruces National Park, Panamá, we reported a predation attempt by P. hastatus on Artibeus jamaicensis. To the best of our knowledge, this constitutes the first predator-prey interaction between both bats and highlights the opportunistic role of P. hastatus as a predator.

Key words: Behavior; Chiroptera; diet; foraging; omnivore; predation.

La familia Phyllostomidae incluye la especie Phyllostomus hastatus, que se distingue por su gran tamaño y amplia distribución; siendo un murciélago omnívoro que se alimenta principalmente de invertebrados y frutos. Sin embargo, existen informes de depredación de pequeños vertebrados, como murciélagos, de los que los casos documentados en la literatura científica suelen ser pocos. Por medio del uso de 2 redes de niebla de 5 anillos de 12 m de largo por 2.5 m de ancho, colocadas principalmente a nivel del suelo a orillas del río Pedro Miguel, en una zona de vegetación secundaria de tierras bajas tropicales, se realizaron capturas mediante el monitoreo de la abundancia y riqueza de murciélagos en el Parque Nacional Camino de Cruces. El 30 de julio de 2024, en el Parque Nacional Camino de Cruces, Panamá, reportamos un intento de depredación por parte de P. hastatus sobre Artibeus jamaicensis. Hasta donde es de nuestro conocimiento, esta constituye la primera interacción depredador-presa entre ambos murciélagos y resalta el papel oportunista de P. hastatus como depredador.

Palabras claves: Alimentación; Chiroptera; comportamiento; depredación; dieta; omnívoro.

© 2024 Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología, www.mastozoologiamexicana.org

Phyllostomus hastatus Pallas (1767), is a dark brown to reddish brown omnivorous species (Laval and Rodríguez-Herrera 2002) belonging to the subfamily Phyllostominae of the family Phyllostomidae (Wilson and Mittermeier 2019), considered the second largest bat in the Neotropical region (Taylor and Tuttle 2019). It is distributed from southern Belize and eastern Guatemala, through Central America to South America including Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Perú, Bolivia, Paraguay and Brazil, also present on the islands of Margarita and Trinidad (Aguirre 2019; Kraker-Castañeda et al. 2023). It usually inhabits large colonies that can comprise up to more than 100 individuals inside caves, tree holes or abandoned houses in a wide variety of ecosystems ranging from primary to secondary forest and even in cultivated or disturbed areas from sea level to 1,800 m (McCracken and Bradbury 1981; Aguirre 2019).

It is known that due to its large size and weight ranging from 55 g to 140 g (Reid 2009; Aguirre 2019), P. hastatus requires a continuous supply of protein-rich food (Cortés-Delgado and Jimenéz-Ferbans 2014; Callejas et al. 2022). Phyllostomus hastatus tends to feed mainly on insects of the orders Orthoptera, Blattodea, Hymenoptera and Coleoptera (Santos et al. 2003), due to their larger body size and its exoskeletons composed of chitin rich in nitrogen and amino acids essential for protein synthesis (Meyer et al. 2011). Phyllostomus hastatus usually consumes fruits and many seeds of Cecropia peltata L. (Ascorra and Wilson 1992) and other plant species of the families Myrtaceae, Musaceae, Solanaceae, Anacardiaceae and Passifloraceae (Santos et al. 2003).

Although it is known that it can also feed on small vertebrates such as birds and mammals, including bats (Costa et al. 2010), records of predation on bats by P. hastatus tend to be unusual to observe in the field, where most cases are probably not reported in the scientific literature because they do not present illustrative evidence (de Souza et al. 2020). Therefore, in this note we present a direct observation of a predation attempt by P. hastatus on an individual of the species Artibeus jamaicensis Leach, 1821.

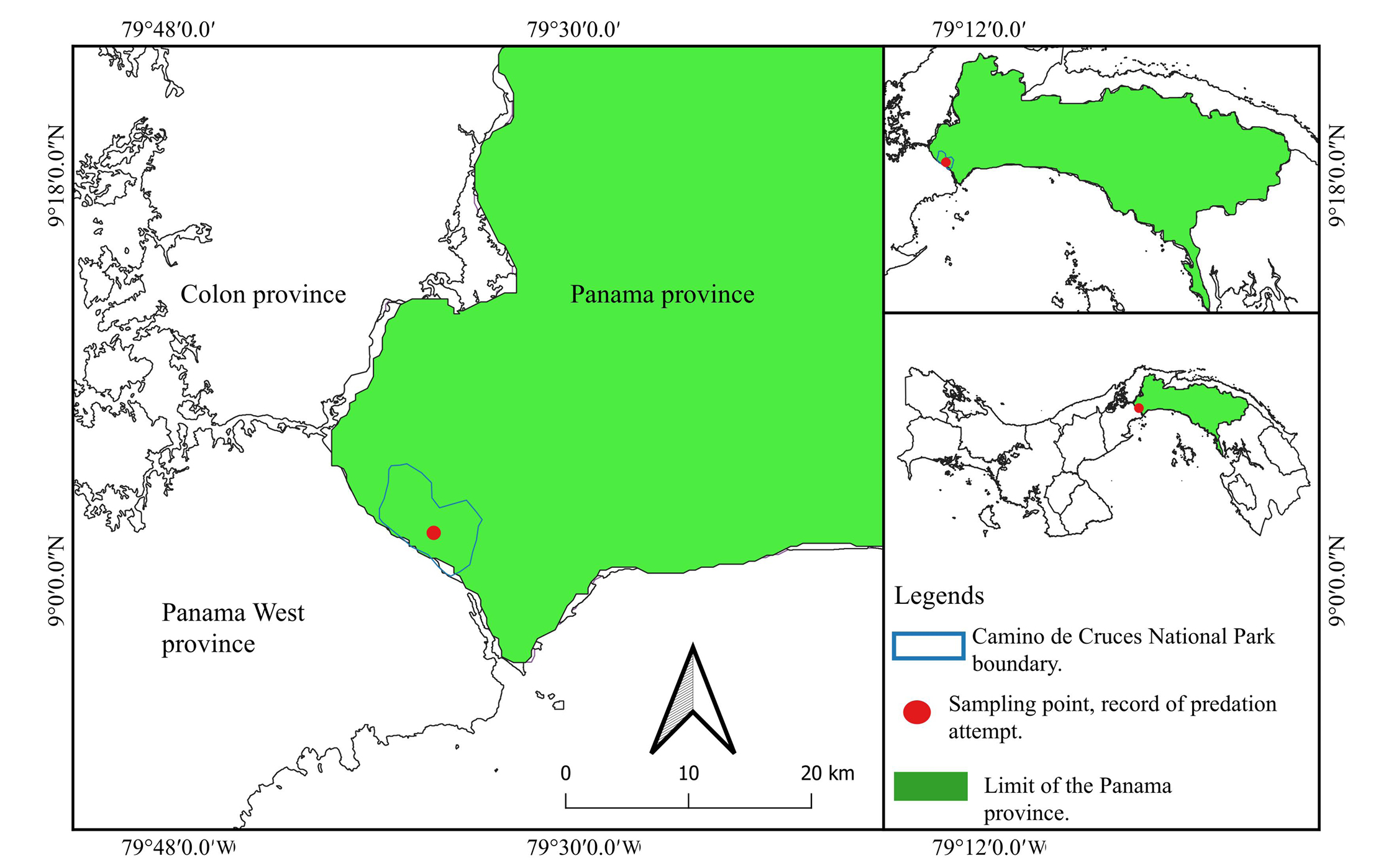

Our observation takes place in Camino de Cruces National Park located north of Panamá City, Panamá Province, coordinates 9° 02' 17.0" N, 79° 36' 45.9 " W (Figure 1), has 4,950 ha of secondary vegetation of tropical lowland semi-deciduous type, quite intervened (ANAM 2010), there is an abundant presence of wild grasses Saccharum spontaneum in the surrounding area and a dominance of tree species such as Anacardium excelsum, Cecropia peltata, Terminalia amazonia, Cedrela odorata, Swietenia macrophylla, Ficus insipida, Enterolobium cyclocarpum and Guazuma ulmifolia. In general, the park is located between 30 to 150 m above sea level with slopes between 4° to 15°; average annual rainfall of 1,801 to 2,100 ml; average annual temperature of 26 °C and a tropical climate with a prolonged dry season (ANAM 2010). Captures were made by monitoring the abundance and richness of bats in the park using 2 12 m long 2.5 m wide 5-ring mist nets, placed mainly at ground level in open spaces between vegetation, ecotones and over shallow rivers and streams (Kunz et al. 2009).

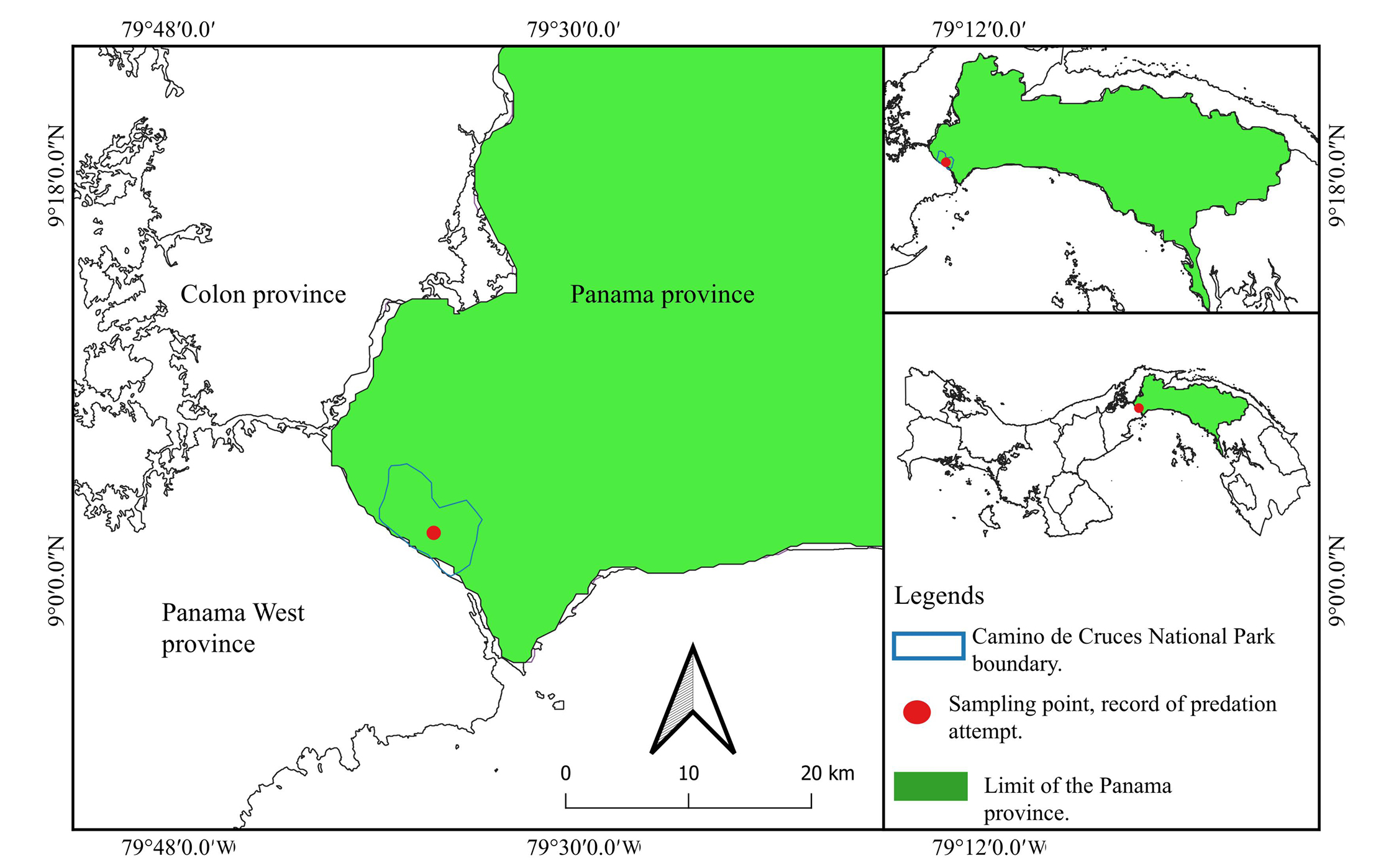

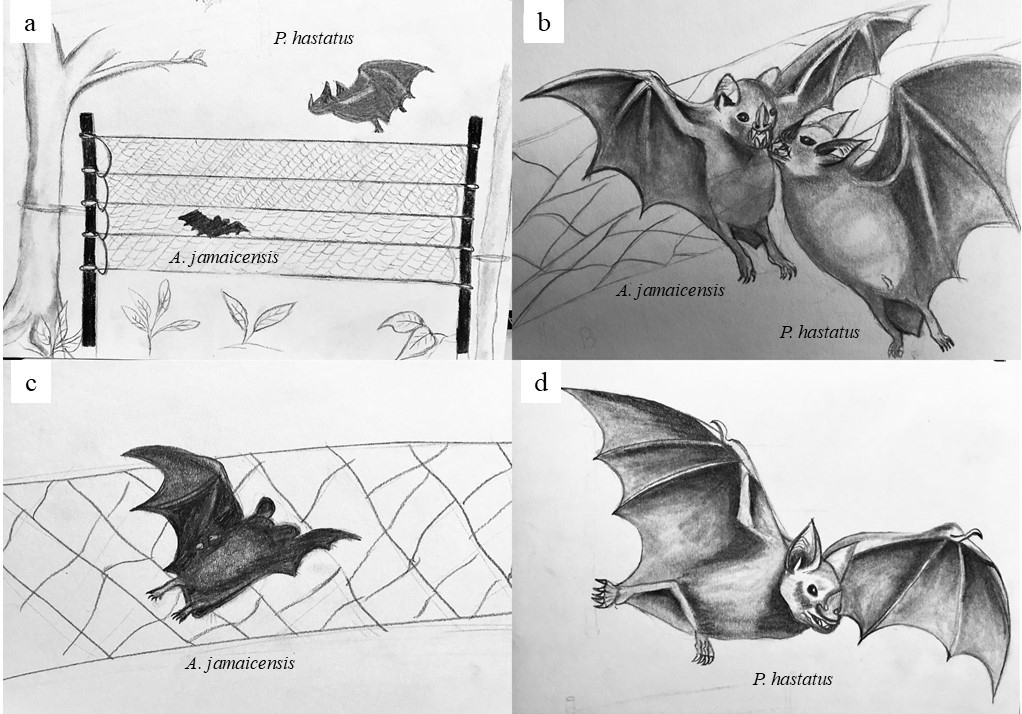

On July 30, 2024, at 11:27 hr, around a gallery forest, between 5 and 7 m from the bank of the Pedro Miguel River, with an abundant presence of Ficus insipida, we report a predation attempt by P. hastatus on a 43 g female subadult individual of A. jamaicensis that was trapped in the net (Figure 2). The predator, which was previously located flying over the sampling point, pounced on the net, causing strong bites on the dorsum and rostrum of A. jamaicensis (Figure 3). However, due to the presence of the researchers, the entanglement of the A. jamaicensis and the fact that the area of the net could not support the weight of both specimens due to the struggle and was therefore damaged, the individual of P. hastatus finally flew away from the net (Figure 2). Minutes later another individual of P. hastatus was observed approaching and colliding with the net, but without making any specific attack. The attacked A. jamaicensis female died shortly thereafter, probably due to the bite on her face. The specimen of A. jamaicensis was not collected due to not having the necessary equipment for its conservation until the end of the field tour, the individual presented the following morphometric data: 60 mm (forearm), 76 mm (body), 12 mm (hind foot), 15 mm (ear).

It should be noted that, during the night and the predation event, it was observed that some individuals of A. jamaicensis and other species captured such as Carollia perspicillata (Linnaeus, 1758), C. castanea Allen, 1890 and Dermanura watsoni (Thomas, 1901), emitted loud vocalizations for help. However, no attempts by P. hastatus towards these individuals were observed.

The individuals involved in the event were identified by means of the characters present in York et al. (2019) for the case of A. jamaicensis and by direct observation of the morphological aspect and large size described in Reid (2009) for the case of P. hastatus. Due to the spontaneous nature of the event and the lack of photographic equipment at the time, it was not possible to capture the attack by means of photographs; therefore, the description is presented by means of illustrative drawings.

It is known that P. hastatus can prey on other small bats, smaller than 50 g both in the field and in captivity (Nowak 1999), especially those that are often found associated with the same roosts, such as Molossus molossus Pallas (1766) and M. rufus Geoffroy (1805) (McNab 2003). However, the first observation of this behavior in the wild was reported by de Souza et al. (2020), who describe a predation event of P. hastatus on C. perspicillata in an abandoned house in the municipality of Paraúna, Goiás, Brazil.

On the other hand, so far, this predatory behavior by P. hastatus towards other smaller bat species trapped in mist nets had been previously reported by Oprea et al. (2006), which recorded 4 predation events involving 2 individuals of Glossophaga soricina Pallas (1766), 1 of Carollia perspicillata and 1 of Myotis nigricans Schinz (1821) in Southeastern Brazil. Apparently, although predation by carnivorous species on other bats captured in mist nets seems to be a rare event, it can be repeated on several occasions; for example, Nogueira et al. (2006) observed a similar case of predation of C. perspicillata by Chrotopterus auritus Peters (1856) in southwestern Brazil. In another case Guevara et al. (2022) reported an attempted predation on nets of Eptesicus furinalis D'Orbigny and Gervais (1847) by Phyllostomus discolor Wagner (1843) in eastern Panamá. According to Bigai and Faria (2018), bats trapped in mist nets are easy prey not only for predatory bats, but also for a range of other mammalian animals such as felids, canids, and marsupials; and birds such as night herons and owls.

According to de Souza et al. (2020), although the data and literature do not suggest that this behavior in P. hastatus is common, it can be assumed that this species may be an opportunistic consumer of small bats, attacking incapacitated adults, neonates and juveniles with limited flight capabilities, and probably bats within roost (Oprea et al. 2006). In Panamá, the specific diet of P. hastatus in different ecosystems is unknown, so future studies based on the stomach contents of the species may shed light on which other vertebrates or common bats of similar size to A. jamaicensis such as C. perspicillata or genera such as Vampyrodes and Molossus, are potential prey for this opportunistic predator.

Acknowledgements

To the staff of Camino de Cruces National Park, E. Morán and J. Segundo for their support and guidance during the sampling tours conducted in the internal grounds of the park. To park director Y. González for providing permission and logistical support to enter the park. We also thank the 2 anonymous reviewers whose comments significantly improved the first version of this note.

Literature cited

Aguirre, L. A. 2019. Phyllostomus hastatus. Pp. 507 in Handbook of the Mammals of the World (Wilson, D. E., and R. A. Mittermeier, eds.). Lynx Edicions. Barcelona, Spain.

Ascorra, C. F., and D. E. Wilson. 1992. Bat frugivory and seed dispersal in the Amazon, Loreto, Peru. Publicaciones del Museo de Historia Natural Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos 43:1-6.

Autoridad Nacional del Ambiente (ANAM) (eds.). 2010. Atlas Ambiental de la República de Panamá. Gobierno Nacional. Ciudad de Panamá, Panamá.

Bigai, L. R., and M. B. Faria. 2018. Eventos predatórios em morcegos do Brasil. Revista de Biología Neotropical 15:96-108.

Callejas, S. H., J. B. Correa, and J. C. Pacheco. 2022. Caracterización de la dieta, refugios y morfometría de Phyllostomus hastatus (Pallas 1767) en sistemas agropecuarios asociados a fragmentos de bosques en Córdoba, Colombia. Degree Thesis, Repositorio Institucional Unicordoba. Córdoba, Colombia.

Cortés-Delgado, N., and L. Jiménez-Ferbans. 2014. Descripción de un refugio usado por Phyllostomus hastatus (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) en la Serranía del Perijá, La Guajira, Colombia. Revista Ciencia e Ingeniería 1:10-14.

Costa, L. M., et al. 2010. Colony size, sex ratio and cohabitation in roosts of Phyllostomus hastatus (Pallas) (Chiroptera: Phyllostomoidae). Brazilian Journal of Biology 70:1047-1053.

de Souza, M. B., et al. 2020. Predação oportunista de Carollia perspicillata (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) pelo morcego Phyllostomus hastatus (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae). Enciclopédia Biosfera 14:554-561.

Guevara, N., M. López, and M. Morales. 2022. Intento de depredación sobre Eptesicus furinalis (Familia: Vespertilionidae) por Phyllostomus discolor (Familia: Phyllostomidae; Subfamilia: Phyllostominae) en la República de Panamá. Tecnociencia 24:78–85.

Kraker-Castañeda, C., et al. 2023. Ampliación del límite noroeste de distribución de Phyllostomus hastatus y descripción de sus pulsos de ecolocalización. Theyra Notes 4:60-67.

Kunz, T. H., R. Hodgkison, and C. D. Weise. 2009. Methods of capturing and handling bats. Pp. 3-35 in Ecological and behavioral methods for the study of bats (Kunz, T. H., and S. Parsons, eds.). Second Edition. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore U.S.A.

Laval, R. K., and B. Rodríguez-Herrera. 2002. Murciélagos de Costa Rica. Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad (INBio). Heredia, Costa Rica.

McCracken, G. F., and J. W. Bradbury. 1981. Social organization and kinship in the polygynous bat Phyllostomus hastatus. Behavioral Ecology Sociobioly 8:11–34.

McNab, B. K. 2003. Standard energetics of phyllostomid bats: the inadequacies of phylogenetic contrast analyses. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 135:357-368.

Meyer, C. F., et al. 2011. Accounting for detectability improves estimates of species richness in tropical bat surveys. Journal of Applied Ecology 48:777-787.

Nogueira, M. R., L. R. Monteiro, and A. L. Peracchi. 2006. New evidence of bat predation by the woolly false vampire bat Chrotopterus auritus. Chiroptera Neotropical 12:286-288.

Nowak, R. M. 1999. Walker’s mammals of the world. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, U.S.A.

Oprea, M., et al. 2006. Bat Predation by Phyllostomus hastatus. Chiroptera Neotropical 12:255-257.

Reid, F. A. 2009. A field guide of the mammals of Central American & Southeast Mexico. Oxford University Press. New York, U.S.A.

Santos, M., et al. 2003. Phyllostomus hastatus. Mammalian Species 722:1-6.

Taylor, M., and M. D. Tuttle. 2019. Bats and illustrated guide to all species. Ivy Press. London, United Kingdom.

Wilson, D. E., and R. A. Mittermeier (eds.). 2019. Handbook of the mammals of the world Vol. 9. Bat. Lynx Edicions. Barcelona, Spain.

York, H. A., et al. 2019. Field keys to the bats of Costa Rica and Nicaragua. Journal of Mammalogy 100:1726-1749.

Associated editor: José F. Moreira Ramírez.

Submitted: August 27, 2024; Reviewed: November 5, 2024.

Accepted: November 7, 2024; Published on line: November 12, 2024.

Figure 1. Recorded point of attempted predation (red point) of the greater spear-nosed bat, Phyllostomus hastatus on the Jamaican fruit bat, Artibeus jamaicensis in Camino de Cruces National Park, Panamá.

Figure 2. Interpretive drawing of predation attempt recorded in Camino de Cruces National Park, Panamá; sequence as described in the results section. a and b) Arrival in flight and attack of Phyllostomus hastatus on Artibeus jamaicensis; c) wounded A. jamaicensis; d) withdrawal of P. hastatus. Drawing author: H. Peralta.

Figure 3. Wounds caused by the bites of Phyllostomus hastatus on different parts of the body of Artibeus jamaicensis. a and b) Right side of the rostrum; c) left side of the rostrum; d) lower dorsal area, left side.