THERYA NOTES 2024, Vol. 5 : 255-260 DOI: 10.12933/therya_notes-24-182 ISSN 2954-3614

Presence of gastrointestinal parasites in Dicotyles tajacu in conservation areas and backyards of Campeche and Yucatán, México

Presencia de parásitos gastrointestinales en Dicotyles tajacu en áreas destinadas para la conservación y traspatios de Campeche y Yucatán, México

Carolina Flota-Bañuelos1*, Frida Estefania Santos-Alcocer2, Víctor Hugo Quej-Chí2, Jael Merari Tun-Kuyoc3,

Rocío del Alba Soberanis-Soberanis3, and Jorge Rodolfo Canul-Solís3

1CONAHCYT-Colegio de Postgraduados Campus Campeche. Carretera Haltunchén-Edzná, km 17.5, C. P. 24450, Champotón. Campeche, México. E-mail: cflota@colpos.mx (CF-B).

2Colegio de Postgraduados Campus Campeche. Carretera Haltunchén-Edzná, km 17.5, C. P. 24450, Champotón. Campeche, México. E-mail: santos.frida@colpos.mx (FES-A); quej@colpos.mx (VHQ-Ch).

3Instituto Tecnológico de Tizimín. Calle 29, Colonia Santa Rita, C. P. 97700, Tizimín. Yucatán, México. E-mail: tunmerari0@gmail.com (JMT-K); 19890220@ittizimin.edu.mx (RAS-S); jcanul31@gmail.com (JRC-S).

*Corresponding author

Dicotyles tajacu faces habitat destruction, free-range poaching, and parasitism in captive animals, which causes diarrhea, weight loss, and death. This study aimed to determine the presence of nematodes and protozoa in peccaries in captivity in Campeche and Yucatán, México. The study was carried out in 2 Management Units for Wildlife Conservation (UMAs, from its name in Spanish) and 1 backyard located in Campeche, and in a Wildlife Management Farm and Facility (PIMVS, from its name in Spanish) in Yucatán, where fecal samples from 47 individuals were collected and placed in labeled polyethylene bags. In the laboratory, feces were processed by sedimentation and flotation, and gastrointestinal parasites were identified based on morphometric characteristics. The data obtained were analyzed using the χ2 test (P ≤ 0.05) in the Statistica v. 9.1 software. The peccaries of PIMVS showed a higher prevalence of parasites, with 53.3 % positive individuals, and the highest parasite load (P ≤ 0.05) due to eggs of the helminth Strongylida sp. and oocysts of the protozoan Eimeria sp. The prevalence recorded and the parasites Strongylida sp. and Eimeria sp. observed in peccaries of the PIMVS were similar to those in zoos in other countries, implying that captive peccaries are more vulnerable to endoparasitism. The determination of endoparasites in D. tajacu is relevant for animal health management in PIMVS, UMAs, and backyards to avoid zoonoses, especially before merging common spaces for the management of 2 or more species.

Key words: Captivity; parasitosis; wildlife; wild pig; zoonosis.

Dicotyles tajacu se enfrenta a la destrucción de su hábitat, cacería furtiva en vida libre y al parasitismo en cautiverio, que provoca diarreas, pérdida de peso y la muerte. El objetivo fue determinar la presencia de nemátodos y protozoos en individuos en cautiverio en Campeche y Yucatán, México. El estudio se realizó en 2 Unidades de Manejo para la Conservación de la Vida Silvestre (UMAS) y 1 traspatio ubicados en Campeche y 1 Predio e Instalación que Maneja Vida Silvestre (PIMVS) en Yucatán, donde se obtuvieron muestras de heces de 47 individuos, que se colocaron en bolsas de polietileno rotuladas. Las heces fueron procesadas mediante sedimentación y flotación, y para la identificación de parásitos gastrointestinales se usaron los caracteres morfométricos. Los datos obtenidos se analizaron mediante la prueba de χ2 (P ≤ 0.05) en el software Statistica v. 9.1. Los pecaríes del PIMVS presentaron mayor prevalencia con 53.3 % individuos positivos y la carga parasitaria más elevada (P ≤ 0.05) debido a la presencia de huevos del helminto Strongylida sp. y ooquistes del coccidio Eimeria sp. La prevalencia registrada y los parásitos de los géneros Strongylida sp. y Eimeria encontradas en el PIMVS, fue similar a zoológicos de otros países, lo que implica que estos animales en espacios cerrados son más vulnerables al endoparasitismo. La determinación de endoparásitos en D. tajacu es relevante para el manejo zoosanitario en PIMVS, UMAS y traspatios, para evitar zoonosis, sobre todo antes de fusionar espacios comunes para el manejo de 2 o más especies.

Palabras clave: Cautiverio; fauna silvestre; parasitosis; puerco de monte; zoonosis.

© 2024 Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología, www.mastozoologiamexicana.org

The collared peccary (Dicotyles tajacu), which belongs to the family Tayassuidae, is a wild pig that plays an important role in ecosystems as a seed disperser, contributing to the spatial distribution of the plants on which it feeds (Beck 2005; Jones and Gutiérrez 2007). It also serves as a link in the food chain, being consumed by predators such as the jaguar (Panthera onca) and the puma (Puma concolor; Moreno et al. 2006). From a socioeconomic standpoint, D. tajacu is among the 20 most important species used in México; its fur is used to manufacture coats and footwear (Fang et al. 2008; Naranjo et al. 2010; Siruco et al. 2011), while its meat is sold in rural areas of Yucatán and Campeche, since peccaries are subjected to poaching (Reyna-Hurtado and Tanner 2007; Fang et al. 2008; Montes and Mukul 2010; Barranco-Vera et al. 2023).

To prevent this species from being included in a population risk category due to indiscriminate poaching in México, the Official Mexican Norm NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (SEMARNAT 2010) has established Management Units for Wildlife Conservation (UMAs, from its name in Spanish) and Wildlife Management Farms and Facilities (PIMVS). These are areas or spaces for the legal management of species where preservation strategies are promoted through maintenance, reproduction, repopulation, environmental education, and reintroduction to natural areas (SEMARNAT 2010). Studies on captive mammals suggest that before releasing animals from UMAs to natural areas, they are tested for parasites to avoid diseases and potential zoonotic risks to wildlife (Mukul-Yerves et al. 2014; Liatis et al. 2017; Sierra et al. 2020), or even death (Menajovsky et al. 2023).

There are records of the presence of endoparasites such as Strongyloides sp. in free-living collared peccary and UMAs, Strongyloides sp., Strongylida (Oesophagostomum sp.), and Eucoccidiorida (Eimeria, Isospora) in the state of Yucatán (Mukul-Yerves et al. 2014). Other endoparasites, such as Ascaris suum, Balantidium sp., Entamoeba polecki, Iodamoeba bütschlii, and Entamoeba polecki, have been reported in captive individuals in Brazil (Silveira et al. 2024). However, studies that have determined parasites in captive peccaries kept in UMAs, PIMVS, and backyards of Campeche and Yucatán, México are scarce, which hinders decision-making about the release of captive specimens or the consumption of their meat. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the presence of gastrointestinal parasites (nematodes and protozoa) in peccaries living in conservation areas and backyards in Campeche and Yucatán, México.

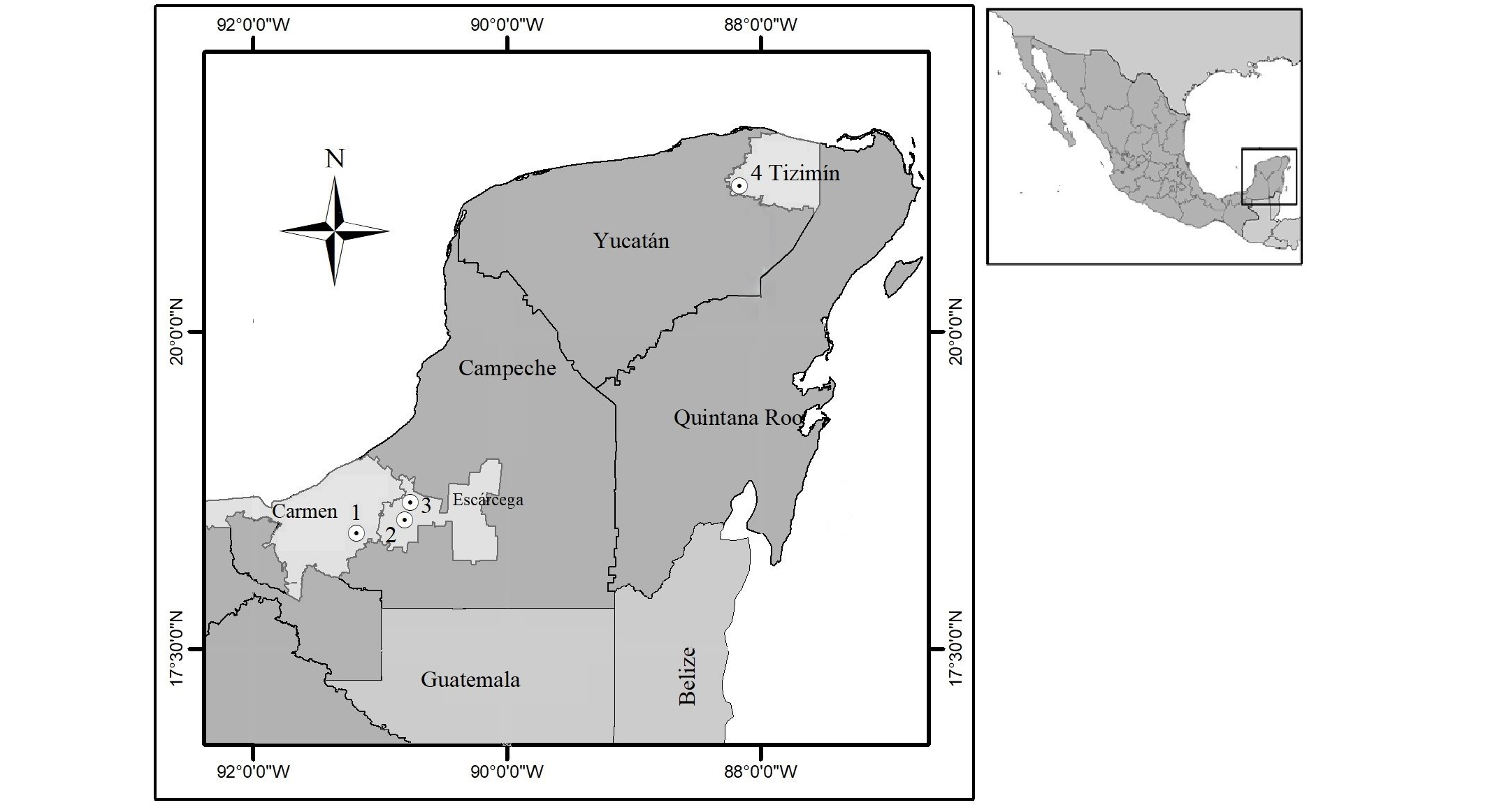

The study was carried out from August to December 2023 in 2 UMAs and 1 backyard in the state of Campeche, and in 1 PIMVS in the state of Yucatán. The characteristics of each site are as follows: Site 1. UMA Ecoturística Monte Nuevo, Senderos Interpretativos y Observaciones de Flora y Fauna (Monte Nuevo Ecotourism UMA, Interpretive Trails and Observations of Flora and Fauna; DGVS-UMA-VL-3699.-CAMP), located in the municipality of El Carmen, Campeche (18° 24' 26.65'' N, 91° 10' 57.39" W), with a warm subhumid climate, mean annual temperature of 25.7 °C, mean annual precipitation of 1,540 mm, and altitude of 24 m (INEGI 2010a). Site 2. UMA Casados Ranch Wildlife Conservation Center (SEMARNAT-UMA-IN-0024-CAMP), located in the municipality of Escárcega, Campeche (18° 36' 7.23" N, 90° 42' 4.54" W), mean annual temperature of 26 °C, mean annual precipitation of 1,200 mm, and altitude of 24 m (INEGI 2009). Site 3. Backyard located in ejido José de la Cruz Blanco, Escárcega, Campeche (18° 37' 02.33" N, 90° 46' 53.3" W), mean annual temperature of 26 ºC, mean annual precipitation of 1,150 mm, and altitude of 95 m (INEGI 2009). Site 4. PIMVS La Reina Zoological and Botanical Park (SEMARNAT-PIMVS-0185-YUC-10), located in the municipality of Tizimín, Yucatán (21º 08' 53.13" N, 88º 09' 38.18" W, at 19 m), mean annual temperature of 27 ºC, mean annual precipitation of 1,000 mm, and altitude of 20 m (INEGI 2010b; Figure 1).

At Site 1, the facilities consist of four 30 m2 yards with cement floor, galvanized-mesh walls, and part of the roof made of galvanized sheets; each yard has drinking troughs and feeders. The diet comprises a mixture of fruits and vegetables, and animals have been born in captivity for more than 10 years. In Site 2, peccaries have been born and live in the wild; there are natural and artificial drinking troughs in the dry season. Site 3 is a 6 m2 yard with an unpaved floor and walls and roof made of galvanized sheets; the drinking trough is a tire split in half. The peccaries kept in this yard were captured from the wild and do not have a feeder; they are fed herbs, tortillas, or vegetable waste. Site 4 is an area of 616 m2 with unpaved floor, galvanized mesh walls, drinking troughs, and cement feeders. The diet comprises a mixture of fruits and vegetables, and animals have been born in captivity for more than 20 years (Figure 2).

Fecal samples were obtained using a non-invasive method. Each animal was observed for 4 hr (6:00 hr to 10:00 hr); when it defecated, its feces were collected with a polyethylene bag labeled with the number and sex of the animal and the site of collection. All samples were kept in an ice box and transported to the Animal Science Laboratory of the College of Postgraduates, Campeche Campus.

In the laboratory, each fecal sample was first homogenized. Then, 2 g was collected for the quantification of protozoan oocysts using the sedimentation methodology (Rodríguez-Vivas et al. 2011); for nematode eggs, the McMaster flotation method was used (Alpízar et al. 1993). Afterward, the McMaster cameras were read, and parasites were identified under a Leica light microscope using the 40x lens and following the taxonomic keys of Soulsby (1987) and Quiroz (1989). The prevalence rate was determined using the formula (Datta et al. 2024): Prevalence = (number of parasitized individuals / number of individuals sampled per site) x 100.

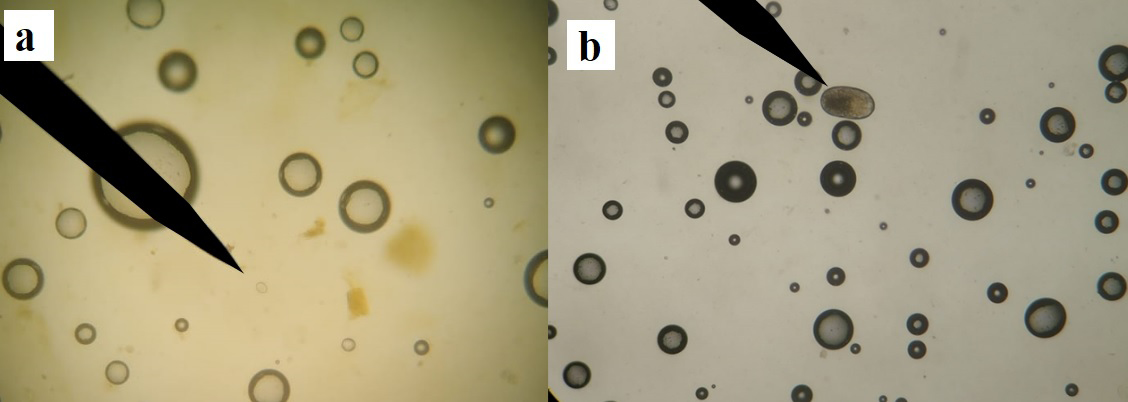

Likewise, photographs of protozoa and cysts were taken from the most representative observations for future studies on parasites (Figure 3). Finally, the parasite load was compared between sites using the χ2 test (León et al. 2019) applying a significance criterion of P ≤ 0.05 in the software Statistica v. 9.1 (STATISTICA 2005). The objective was to determine which management type (UMA, PIMVS, or backyard) concentrated the largest number of gastrointestinal parasites.

In total, fecal samples were collected from 47 collared peccaries. Of these, 25.5 % were positive for gastrointestinal parasites, with the highest prevalence at Site 4, where 53.3 % of individuals were positive for endoparasites (Table 1).

The parasites quantified in collared peccaries included eggs of the helminth Strongylida sp. and oocysts of the protozoan Eimeria sp. (Figure 3). The site with the highest number of parasites was Site 4, with 173.33 parasites (P ≤ 0.05). The number of eggs of Strongylida sp. was not significantly different (P ≥ 0.05) between sites, while the highest number of Eimeria sp. oocysts was recorded at Site 4, with an average of 166.64 oocysts (P ≤ 0.05). This was the only site where peccaries were parasitized with both Strongylida sp. and Eimeria sp. (Table 2).

Of the 4 study sites, the collared peccaries of Site 4 (PIMVS, Yucatán) had a parasite prevalence of 53.3 % and a higher parasite load of Strongylida sp. eggs and Eimeria sp. oocysts than the UMAs and backyard of Campeche. This is probably because at Site 4, peccaries coexist in the same yard with goats (Capra hircus) and donkeys (Equus asinus), which are potential hosts of these parasites (Quiroz et al. 2011) and excrete them through the feces. Furthermore, since the floor is unpaved, trampling promotes the volatility of oocysts and eggs in the dust and their deposition in the water and food consumed by captive animals (Botero and Restrepo 2012). This environment promotes the proliferation of helminths and coccidia and, therefore, involves a greater possibility of parasite dispersal (Mukul-Yerves et al. 2014). A higher prevalence was found in a Rio de Janeiro Zoo, Brazil, with 100 % of peccaries giving positive for nematode larvae and eggs of Strongylida sp., as well as another endoparasite, Balantioides coli (Barbosa et al. 2020). In this sense, Ortiz-Pineda et al. (2019) noted that wild animals are more vulnerable to endoparasitism when they are in closed captivity, such as in PIMVS, zoos, and UMAs (Salmorán-Gómez et al. 2019).

No infestation scales have been established to differentiate the parasite loads caused by gastrointestinal parasites in Tayassuidae. However, when comparing the parasite load recorded in the present study with those previously reported for other domestic species (sheep and cattle; a mild load of 50 to 200 eggs per gram (epg) of feces; moderate, ˃ 200 to < 800 epg; and high, ˃ 800 epg; Morales et al. 2006), the load recorded in collared peccaries from Site 4 (PIMVS) corresponds to a mild-to-moderate infestation (Morales et al. 2006; Boldbaatar et al. 2021). Therefore, it is recommended that collared peccaries be tested for parasites prior to their release. We recommend including leaves of Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit (Fabaceae; de Castro et al. 2024) in the diet, as it functions as a natural antiparasitic agent in other species, such as sheep, cattle, and pigs (Sandoval-Castro et al. 2012; Soares et al. 2015).

The results recorded in this study suggest that the sites where peccaries are kept in captivity should be disinfected, mainly the area where drinking troughs and feeders are installed. Feces should be cleaned weekly to avoid accumulation on the ground, reduce parasitic proliferation that affects their health, and thus avoid zoonoses.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the project CONV_RGAA_2023_50 Caracterización integral de Pecari tajacu e implementación de estrategias para el uso y aprovechamiento sustentable en el estado de Campeche, México (Comprehensive characterization of Pecari tajacu and implementation of strategies for sustainable use and exploitation in the state of Campeche, México). Thanks also to those responsible for the management and backyard units for the support granted to carry out the study. The authors thank the anonymous reviewers whose comments improved the first version of this note. M. E. Sánchez-Salazar translated the manuscript into English.

Literature cited

Alpízar, J. L., et al. 1993. Epizootiología de los parásitos gastrointestinales en bovinos del estado de Yucatán. Veterinaria México 24:189-193.

Barbosa, A. S., et al. 2020. Parásitos gastrointestinales en animales en cautiverio en el Zoológico de Río de Janeiro. Acta Parasitológica 65:237-249.

Barranco-Vera, S. J., et al. 2023. Use of fauna in homegardens and forest in two mayan communities of Yucatán, México. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems 26:1-14.

Beck, H. 2005. Seed predation and dispersal by peccaries throughout the Neotropics and its consequences: a review and synthesis. Pp. 77-115 in Seed fate: predation, dispersal, and seedling establishment (Lambert, J. E., et al., eds.). CABI Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Boldbaatar, B., et al. 2021. Estado clínico-parasitológico de bovinos jóvenes y efecto de antihelmínticos sobre conteos fecales de huevos de estrongilidos gastrointestinales. Revista de Salud Animal 43:1-11.

Botero, D., and M. Restrepo. 2012. Parasitosis intestinales por protozoos. Pp. 37-118 in Parasitosis Humanas (Corporación para Investigaciones Biológicas, ed.). Medellín, Colombia.

Datta, R., et al. 2024. Determination of prevalence and associated risk factors of gastrointestinal nematodes in cattle at Sylhet Region, Bangladesh. Asian Journal of Life Sciences 12:59-63.

de Castro, R., et al. 2024. Seed hydration memory in the invasive alien species Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit (Fabaceae) in the Caatinga. Journal of Arid Environments 224:1-10.

Fang, G.T., et al. 2008. Certificación de pieles de pecaríes en la Amazonía Peruana. Editorial Wust. Lima, Perú.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 2009. Prontuario de información geográfica municipal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, Escárcega, Campeche. Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática. México City, México. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/app/mexicocifras/datos_geograficos/04/04009.pdf. Accessed on January 12, 2024.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 2010a. Compendio de información geográfica municipal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos Carmen, Campeche. Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática. México City, México. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/app/mexicocifras/datos_geograficos/04/04003.pdf. Accessed on January 12, 2024.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 2010b. Compendio de información geográfica municipal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos Tizimín, Yucatán. Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática. México City, México. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/app/mexicocifras/datos_geograficos/31/31096.pdf. Accessed on January 14, 2024.

Jones, C. G., and J. L. Gutiérrez. 2007. On the purpose, meaning, and usage of the physical ecosystem engineering concept. Ecosystem Engineers: Plants to Protists 4:3-24.

León, J. C., et al. 2019. Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in cattle and sheep in three municipalities in the Colombian Northeastern Mountain. Veterinary World 12:48-54.

Liatis, T. K., et al. 2017. Endoparasites of wild mammals sheltered in wildlife hospitals and rehabilitation centres in Greece. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 4:1-8.

Menajovsky, M. F., et al. 2023. Infectious diseases of interest for the conservation of peccaries in the Amazon: A systematic quantitative review. Biological Conservation 277:1-8.

Montes, P. R., and Y. J. Mukul. 2010. Ganadería alternativa. Pp. 496 in Biodiversidad y Desarrollo Humano en Yucatán (Durán, G. R., and G. M. Méndez, eds.). Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán. Mérida, México.

Morales, G., et al. 2006. Niveles de infestación parasitaria, condición corporal y valores de hematocrito en bovinos resistentes, resilientes y acumuladores de parásitos en un rebaño Criollo Río Limón. Zootecnia Tropical 24:333-346.

Moreno, R. R., et al. 2006. Competitive release in diets of Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) and Puma (Puma concolor) after Jaguar (Panthera onca) decline. Journal of Mammalogy 87:808-816.

Mukul-Yerves, J. M., et al. 2014. Parásitos gastrointestinales y ectoparásitos de ungulados silvestres en condiciones de vida libre y cautiverio en el trópico mexicano. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Pecuarias 5:459-469.

Naranjo, E. J., et al. 2010. La cacería en México. Biodiversitas 9:6-10.

Ortiz-Pineda, M. C., et al. 2019. Identificación de parásitos gastrointestinales en mamíferos del zoológico Guátika (Tibasosa, Colombia). Pensamiento y Acción 26:31-44.

Quiroz, R. H. 1989. Parasitología y enfermedades parasitaria en animales domésticos. Limusa. México City, México.

Quiroz, R. H., et al. 2011. Epidemiología de enfermedades parasitarias en animales domésticos. FMVZ UNAM. México City, México.

Reyna-Hurtado, R., and G. W. Tanner. 2007. Ungulate relative abundance in hunted and non-hunted sites in Calakmul Forest (Southern Mexico). Biodiversity Conservation 16:743-757.

Rodríguez-Vivas, R. I., et al. 2011. Epidemiología, diagnóstico y control de la coccidiosis bovina. Pp. 52-66 in Epidemiología de enfermedades parasitarias en animales domésticos (Quiroz, R., C. J. Figueroa, and A. López, eds.). Asociación Mexicana de Parasitólogos Veterinarios AMPAVE. México City, México.

Salmorán-Gómez, C., et al. 2019. Endoparásitos de Odocoileus virginianus y Mazama temama bajo cautiverio en Veracruz, México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Pecuarias 10:986-999.

Sandoval-Castro, C., et al. 2012. Using plant bioactive materials to control gastrointestinal tract helminths in livestock. Animal Feed Science and Technology 176:192-201.

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT). 2010. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010. Protección ambiental-especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres-categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio-lista de especies en riesgo. Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. México City, México. November 26, 2010.

Sierra, Y. D., et al. 2020. Parásitos gastrointestinales en mamíferos silvestres cautivos en el Centro de Fauna de San Emigdio, Palmira (Colombia). Revista de la Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y de Zootecnia 67:230-238.

Silveira, J. A., et al. 2024. Preparing Collared Peccary (Pecari tajacu Linnaeus, 1758) for reintroduction into the wild: a screening for parasites and hemopathogens of a captive population. Pathogens 13:1-16.

Siruco, F. L., et al. 2011. Sex-and age related morphofunctional differences in skulls of Tayassu pecari and Pecari tajacu (Artiodactyla: Tayassuidae). Journal of Mammalogy 92:828-839.

Soares, A. M., et al. 2015. Anthelmintic activity of Leucaena leucocephala protein extracts on Haemonchus contortus. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinaria 24:396-401.

Soulsby, E. J. 1987. Parasitología y enfermedades parasitarias de los animales domésticos. Ediciones Nueva Interamericana. México City, México.

STATISTICA. 2005. Data analysis software system, version 7.1. www.statsoft.com. Accessed on December 8, 2023.

Associated editor: José F. Moreira Ramírez.

Submitted: June 4, 2024; Reviewed: September 12, 2024.

Accepted: October 14, 2024; Published on line: October 22, 2024.

Figure 1. Map with the geographic location of the 4 sampling sites of Dicotyles tajacu at site 1. UMA Carmen, Campeche; site 2. UMA Escárcega, Campeche; site 3. Backyard Escárcega, Campeche; site 4. PIMVS Tizimín, Yucatán.

Figure 2. Specimens of collared peccaries, Dicotyles tajacu at the sampling sites, a) site 1, UMA in Carmen, Campeche; b) site 2, UMA in Escárcega, Campeche; c) site 3, Backyard in Escárcega, Campeche; and d) site 4, PIMVS in Tizimín, Yucatán. Images available on cflota@colpos.mx.

Table 1. Percentage of prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in Dicotyles tajacu in 2 Management Units for Wildlife Conservation (UMAs) and 1 backyard located in Campeche and one Wildlife Management Farm and Facility (PIMVS) in Yucatán, México.

|

Sites |

n |

Number of positive animals |

% prevalence |

Confidence interval (95 %) |

|

1 UMA |

12 |

1 |

8.3 |

0.00- 24.65 |

|

2 UMA |

10 |

2 |

20 |

0.00-46 |

|

3 Backyard |

10 |

2 |

20 |

0.00-46 |

|

4 PIMVS |

15 |

8 |

53.3 |

58-289 |

|

Total |

47 |

13 |

25.5 |

23.26-108.63 |

Figure 3. Gastrointestinal parasites in collared peccary, Dicotyles tajacu: a) oocyst of Eimeria sp.; b) egg of helminth Strongylida sp. Images available on cflota@colpos.mx.

Table 2. Load of parasitic nematodes and protozoa in Dicotyles tajacu from Campeche and Yucatán, México. n (number of individuals), SD (standard deviation). a,bDifferent literals in columns indicate significant differences between sites.

|

Sites |

n |

Strongylida sp. Average ± SD |

Eimeria sp. Average ± SD |

Total parasites ± SD |

|

1 |

12 |

8.3 ± 28.67a |

0a |

8.33 ± 28.87a |

|

2 |

10 |

20 ± 42.16a |

0a |

19 ± 42.16a |

|

3 |

10 |

0a |

20 ± 42.16a |

20 ± 42.16a |

|

4 |

15 |

6.7 ± 25.82a |

166.67 ± 225.72b |

173.33 ± 228.24b |

|

χ2 = 2.69 P = 0.44 |

χ2 = 15.15 P = 0.0017 |

χ2 = 7.76 P = 0.05 |